America’s War in Afghanistan Is Over but Our Big Lies About It Live On

John Moore/Getty

After a collapse that took everyone off guard, “experts” retreated further into comforting fantasies about the mission and its significance rather than finally facing reality.

The last American plane left Afghanistan just before midnight in Kabul after more than a decade of lazy showrunners letting self-proclaimed experts go on about how the Afghan government was making progress and the nation’s security forces were building capacity and securing the country. Now, it turns out, that what we called Afghanistan was always a fiction—a proxy of the United States, dependent on our military and doomed to failure without it.

And because the show is a ratings hit again, however briefly and terribly, the war is ending with those same “experts” jamming the airwaves with malarkey since they’re the only people the TV news bookers and assigning editors know to call. Fulminating against how the withdrawal has been carried out, they slake their anger and hide their embarrassment at having been so wrong for so long with brazen half-truths and outright falsehoods.

The overall effect is to wear American citizens out, to have viewers throw up their arms in exhaustion, and to deny President Joe Biden and those in favor of the withdrawal any measure of satisfaction for an unequivocal good for the country and its long-term foreign policy prospects. To do that, they depend on American ignorance about Afghanistan and disinterest in the history of the country during our occupation of it. On American TV, the war is just one storyline among many in what was the Bush show, and then the Obama show, and then the Trump show, and now the Biden show.

But this is not merely a storyline. The real world and the details matter—it’s just a question of finding the ones that are truly significant. It’s a good thing to take stock after a disaster. I know from my own experience in two deployments as an infantry officer to Afghanistan that the question is if we are going to learn things that may help prevent future disasters or repeat the lies that led us to this one.

Take Bagram Airfield (BAF), which until this month’s retreat had been the primary hub of U.S. activity in Afghanistan for two decades, and the eight-mile run route that followed its perimeter. It took about an hour to complete at a leisurely clip. Stop and think for a moment about what it would actually take to defend and supply an eight-mile perimeter, let alone in the midst of an evacuation effort and without control of the surrounding areas.

The Forward Operating Base (FOB Bermel, later FOB Boris) at which I spent the bulk of my first deployment, by contrast, offered a short, 400-meter course that navigated the pits that were used to burn trash and human waste. The dirt path was outside the gates of the FOB, but inside the wire. Packs of wild dogs were a threat, so people would sometimes run carrying a pistol for self-defense.

FOB Boris required a little more than an infantry platoon working in shifts to secure it properly. If one counts the Combat Outposts to the north and east, each of which were large enough to accommodate a platoon and played a role in securing FOB Boris, one could say that the requirements for base security were more like three platoons. A total of six line platoons were stationed there, along with a platoon of artillerymen, a detachment of cooks, communications specialists, and a severely overworked squad of Army mechanics. An Afghan National Army (ANA) base just off our own but separated by a gate was secured by a platoon of ANA and Afghan National Police (ANP), so that ought to be considered, too.

It’s important to establish these details, because these are the things people overlook when describing what has become one of the most popular criticisms of Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan: that he allowed the military to “abandon” BAF, or that it would have been somehow more possible or feasible to carry out a deliberate evacuation from BAF than from Hamid Karzai International Airport. This is false. The number of people required to safely secure BAF and its eight-mile perimeter in 2021 would have required an entirely new troop surge numbering in the thousands. When one considers the logistics involved, and the numbers of soldiers, Marines, and airmen, the number could have easily ballooned far greater than the number readily available for the task.

It also would have required taking Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) to create an outer perimeter of security. Several months ago, it would have been unimaginable to carry out a unilateral operation. These choices would have affected which ANSF units were available to provide security elsewhere. And one must also consider in retrospect that the ANSF providing security would have also probably required support from the American base logistics system.

The collapse of Afghanistan demonstrated that the country I imagined when I was deployed here was also a lie, just another storyline. It has been extraordinary to watch how in the intervening weeks, rather than facing up to the delusion that we entertained for 20 years, nearly everyone with a hand in this mess has done everything they could to shift the blame elsewhere. Certainly, some leaders were capable of and interested in considering the significance of Afghanistan’s near-instantaneous collapse. Admiral Mike Mullen, for example, didn’t shy away from reality. But the former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff didn’t have much company. Most of the other people who led the war and promoted it have indulged in rationalizing, comforting counterfactuals and even outright lies.

That the evacuation could have been anticipated is one lie that requires acknowledgment. That it might have been more orderly or been conducted more effectively had we retained BAF is another. These alternate reality histories read like fanciful novels exploring similar what-ifs throughout global history. What if Hitler had won at Dunkirk? What if Napoleon had won at Waterloo? What does it matter? They didn’t.

The BAF lie speaks to the human desire to make sense of tragedy. The evacuation has been a disaster, and should have been handled differently. It is as reasonable from that perspective to say that we ought to have conducted it at BAF as it is to say the president should have surged some number of additional people to the State Department to read and review Special Immigrant Visa paperwork.

But this is the problem with counterfactuals: If we had known the withdrawal would be a disaster, we probably wouldn’t have withdrawn, and certainly not under these circumstances.

For all the belated protestations to the contrary, it was not known that the withdrawal would precipitate the collapse of Afghanistan. It was known that the Afghan government was weak and that it would be a struggle for it to survive without American assistance. Pessimists projected that the government would fall after about a year’s worth of fighting. Optimists like myself said the government had a chance to hang on and hammer out a power-sharing agreement.

If the truth had been widely known—that after 20 years, the country we called Afghanistan was totally and essentially dependent on the U.S. military, and could not survive a single month without it—it would have prompted deep soul-searching and some reasonable calls for accountability. The media would presumably have been outraged. And let us not forget, until very recently, the media was almost silent on this subject. Writers, researchers, and investigators were all more concerned about detailing Afghan governmental corruption and identifying ways in which the rights of women were being abused. In other words, the assumption in popular media (when they covered the country at all, which the news networks rarely did) and in national security circles was that Afghanistan was a developing country, cobbled together with duct tape, old two-by-fours hammered haphazardly together, wheezing along, slowly improving.

Except it wasn’t. Afghanistan the way we thought of it simply didn’t exist.

An example of how even seasoned Afghan veterans and thinkers tricked themselves into seeing something that wasn’t there has been the outrage over and around lists of Afghan immigrants (not, technically, refugees) that were given to the Taliban to facilitate movement through their security cordon en route to the airfield. Some have compared this to the lists Nazis used during World War II to identify people of Jewish ancestry. That is a profound and fundamental misunderstanding of Afghan culture and the reason those Afghans were trying to immigrate in the first place.

The Germans, like ourselves, are a nation of lists, names on spreadsheets that say who might report for duty if called up for military service, who owes what tax money to whom, who is associated with which license plate that was seen driving across the Whitestone Bridge on a Friday night with no E-ZPass and now owes $10. Afghanistan is a collection of friends, cousins, nephews, brothers, and sisters, and just as the state knows when one has evaded paying money that the state is owed, in Afghanistan, if one is out walking at night by oneself, or with an unattached woman, one can be sure that it will be known, quickly, and by everyone.

Afghan refugees board a bus at Dulles International Airport after being evacuated from Kabul following the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan.

Olivier Douliery/AFP via Getty

So it was that people working for the government or the ANSF had relatives or acquaintances working for the Taliban; so it is that people working for the Taliban have relatives or acquaintances who worked for the government or the ANSF. No list is needed. It’s not how important information gets recorded or stored. It is an entirely different system. The Taliban aren’t the Nazis, though one could be forgiven for coming away from having read The Kite Runner or its sequel with that conclusion.

Everyone who is leaving Afghanistan and generations of life and memory behind are doing so because they are already known to the Taliban. Their names could be on one list, a hundred lists, or no lists, and it wouldn’t make a bit of difference. It would make a difference to us, but recent aesthetic choices excepted, the Taliban’s system has little or nothing in common with our own.

Here are some other lies I’ve seen. 1) The withdrawal has damaged U.S. credibility with its allies. No, it hasn’t. America has the same degree of credibility with its allies that it had before withdrawing from Afghanistan. The withdrawal may have damaged the reputation of individuals who did not expect President Biden to execute it, but that is another different thing. 2) The civilian casualties created by U.S. operations were worth the terrorists that were killed or apprehended as a result of them. No, the ends don’t justify the means. 3) Some kind of narrative or propaganda or procedure could have been done differently to counter Taliban propaganda. Counterfactual, unproductive, useless wasted words.

The worst lie, to my mind, though—the one that truly exposes its proponents as living in a fantasy world, and not a well-constructed one—is that the status quo was durable. That none of this needed to happen, and that the U.S. could have maintained a small footprint in Afghanistan for years or decades, “indefinitely.” This is a lie that normal people use every day to stave off fears about death, and is understandable at that level. But when former ambassadors in major media outlets, prominent think-tankers, and national security experts on social media platforms employ the fiction of a never-ending present to argue that the Afghan status quo enforced by American violence was sustainable even in the near term, with a Taliban that was obviously far more capable and confident than we gave them credit for, and a government that didn’t exist, boils the blood.

This “status quo” lie depends on readers not paying any attention to Afghanistan. It makes sense if a person’s first encounter with Afghanistan is the media coverage of America’s withdrawal. This coverage consists of crowds of former interpreters and stranded foreigners who fear the Taliban, and presumably supported the status quo ante. What this coverage doesn’t show is the steady march of the Taliban into Afghanistan’s rural areas, months and years of grinding down Afghan military and governance capacity even with an American presence. Proponents of the status quo cannot for whatever reason face the fact that the Afghanistan they describe had not existed for years, possibly ever.

These delusions all express an overt or subconscious desire not to see reality for what it is. Another sort of lie, intended to stonewall or deceive, has been employed routinely by the Biden administration. Through statements that contradict reported truths or offer rosy assessments, the administration has gaslit reporters and readers familiar with the situation on the ground, sowing mistrust and incurring ill will to no clear purpose.

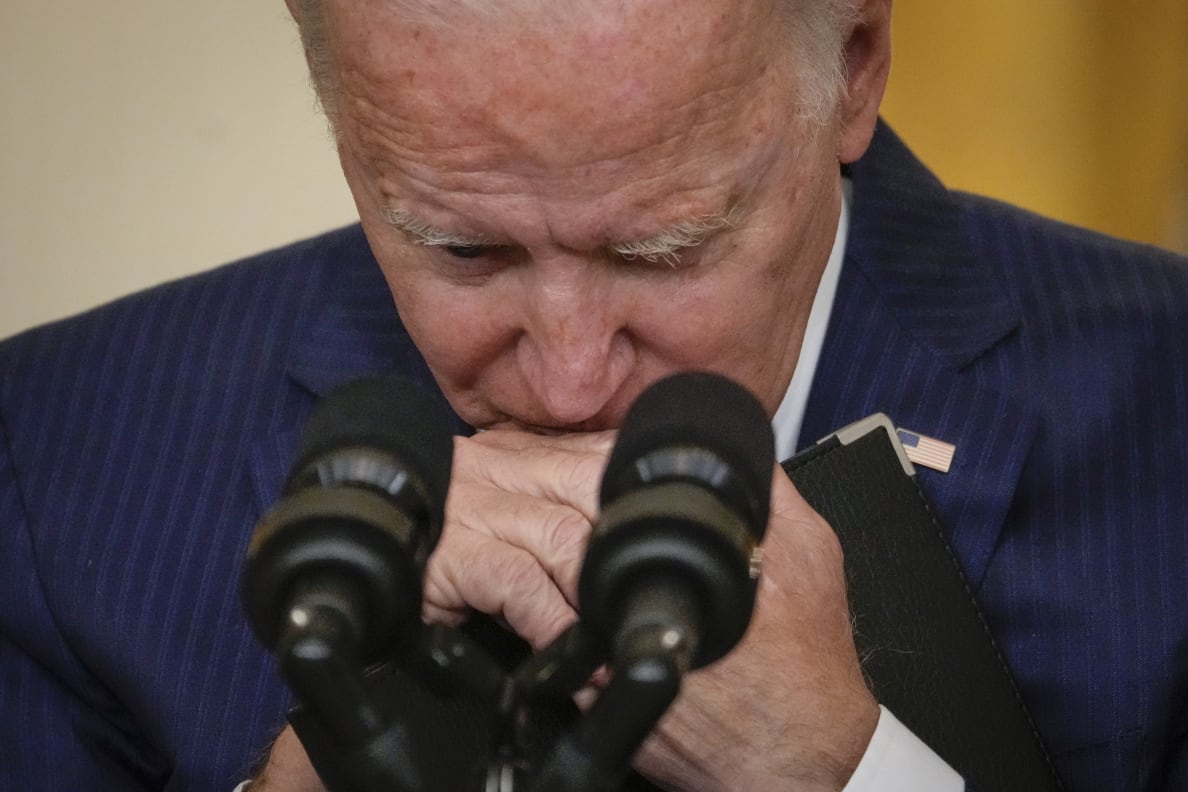

President Joe Biden pauses while listening to a question from a reporter about the situation in Afghanistan on Aug. 26.

Drew Angerer/Getty

It’s been embarrassing watching the administration attempt to shuck responsibility as Biden did when he accused the ANSF of cowardice. There’s plenty of fair blame to go around for the evacuation of Afghan allies. If Biden wants to be recognized for the withdrawal—a good thing— he has to acknowledge his administration’s accountability for the manner in which the subsequent evacuation unfolded, including the chaotic scenes over the last two weeks.

The American withdrawal has been a calamity for hundreds of thousands of American allies who unexpectedly found themselves in another country earlier this month. We thought the government of Afghanistan had been properly equipped and funded to carry out a war of self-defense against the Taliban. We didn’t suppose that there wasn’t a government and that there wouldn’t be a war. We didn’t see that we’d deluded ourselves into seeing a door where there was no door and a home where there was no home.

There has been one comfort from all the horror. Legions of veterans, active duty military, and diplomats have worked tirelessly to welcome these unexpected Afghan immigrants to the United States. It has become popular to criticize the country as essentially white supremacist, or isolationist, or hostile to people of different backgrounds. Seeing the overwhelming grassroots efforts to bring Afghans to the United States and to set them up for success, it’s nice to realize that these criticisms are themselves a kind of lie, a neurotic spiraling of anti-Americanism that doesn’t hold up when examined. After all this time, America is still a haven for those fleeing tyranny. That is the truth.

Adrian Bonenberger is a writer and Army veteran who served two deployments to Afghanistan as an infantry officer. He is the author of the books Afghan Post and The Disappointed Soldier and Other Stories From War, and his essays and reporting have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post and Foreign Policy