Thirty years ago, President Ronald Reagan offered the country a pithy panacea for its economic woes. “Government is not the solution to our problem,” he said. “Government is the problem.”

With a debt crisis looming large over the economy, and the unemployment rate still stubbornly high, many have once again decried government spending as public enemy No. 1. Yet for Andrew Liveris, the head of The Dow Chemical Company, and one of America’s most prominent corporate leaders, blaming the government oversimplifies the problem—and actually compounds it. “We want… government,” he said in an interview with The Daily Beast. “Not big government or small government, but smart government. We need a modern-era advanced manufacturing strategy for this country.”

In the short term, Liveris says the U.S. needs to bridge the partisan divide over spending, and put the United States on the fiscal right track, both by cutting costs and increasing revenue. Yet that in and of itself won’t be enough to restore American growth and prosperity. For that to occur, Liveris says that the U.S. needs to move beyond the false dichotomy of free markets vs. state socialism, and use government resources and private sector know-how to re-invigorate the country’s dwindling manufacturing sector.

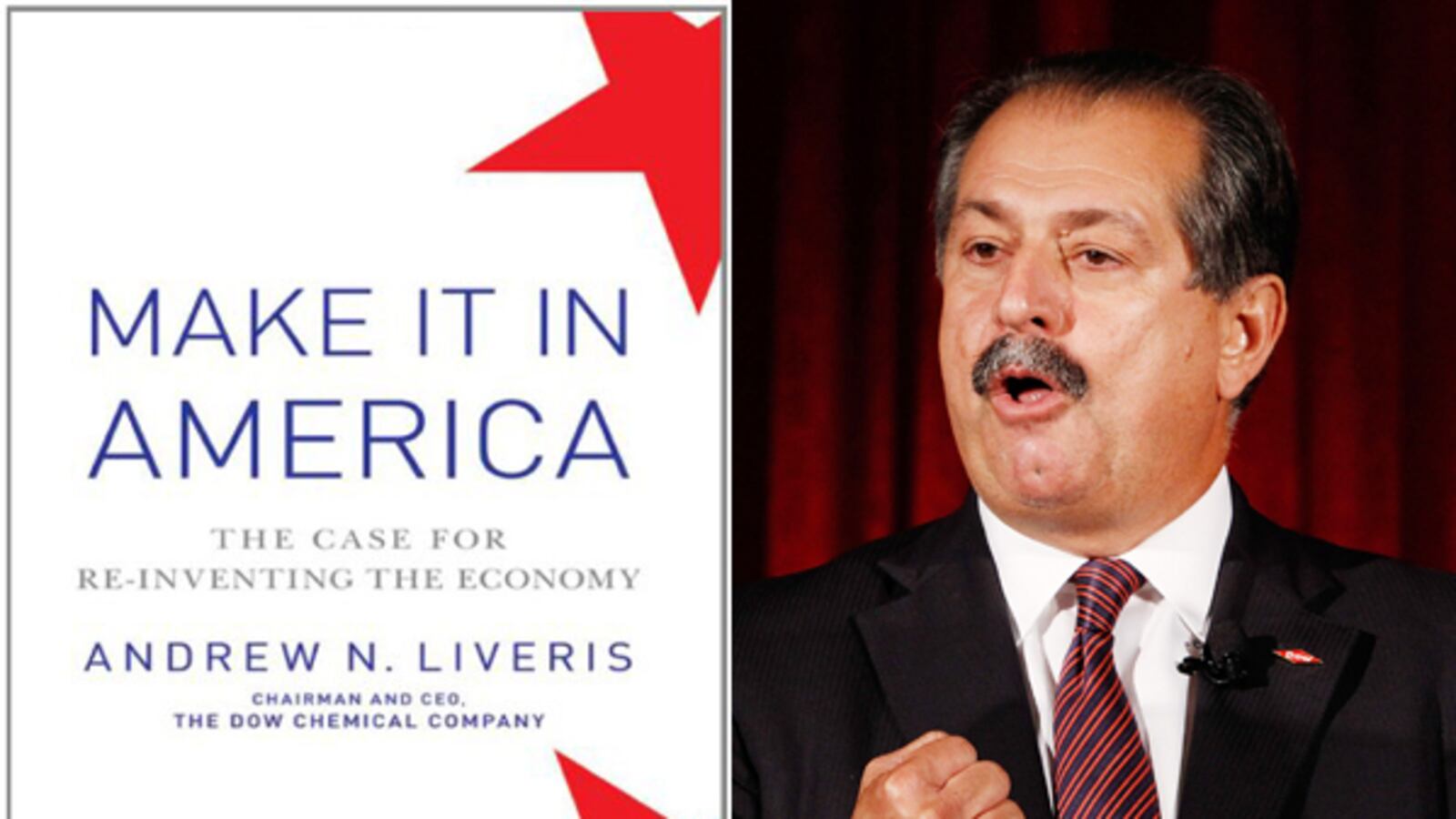

“The United States no longer has an economic model that’s sustainable,” he writes in his recent book Make It in America: The Case for Re-Inventing the Economy. “At the center of our economic problems lies the hole that was left when manufacturing started to disappear. And at the center of our solution is a strategy to rebuild that once-vibrant sector.”

Liveris—who is ethnically Greek, but was born in Australia and resides in Michigan—is hardly the first to mourn the loss of American manufacturing. In 1992, Ross Perot, a third-party candidate for president, famously said that the North American Free Trade Agreement would produce “a giant sucking sound,” of jobs moving south to Mexico.

Yet Perot’s fears were largely forgotten—at least among lawmakers and business leaders—amid the free-market euphoria that ensued with the fall of communism and the rise of the Internet. And with good reason. The U.S. economy created more than 20 million jobs during the eight years that President Bill Clinton was in office; median male earnings rose for the first time in decades. The service sector was going to be the new manufacturing—or such was the conventional wisdom at the time, as economists offered a seemingly sound rationale: Fewer people were employed in manufacturing, but that’s because technology made the process more efficient. Meanwhile, that “giant sucking sound” that Perot described was merely the loss of low-skill labor which could in theory be replaced by the high-tech jobs of the future.

The 2000s have proven the conventional wisdom wrong. Free trade did help create growth, yet between 2001 and 2010, U.S. companies closed more than 42,000 factories, and one-third of all manufacturing jobs—5.5 million of them—have disappeared. “The entire sector is hemorrhaging,” writes Liveris. “Over the past several decades, the United States has watched entire industries disappear from its shores—only to reappear abroad.”

Yet instead of creating an equivalent number of new jobs in equally well-paying sectors, “we entrusted our growth to borrowing and consumerism,” writes Liveris. “We fueled our growth with debt, and with the idea that everything would be fine. As we now know, it wasn’t [and]… too many of us didn’t see it coming.”

What’s most harrowing, however, is not that the U.S. has lost manufacturing jobs in sectors like automobiles or furniture, but that more recent manufacturing losses in, say, the semiconductor industry have set the U.S. up to lose the manufacturing jobs of the future. As Liveris explains, American research and development dollars created the technologies behind LCD televisions. Yet because manufacturers in Asia offered companies better incentives than their American counterparts, those jobs went overseas. Newer devices such as Amazon’s Kindle are manufactured using similar technology, and thus the very same foreign manufacturers were in a better position to snatch up those jobs as well. “Today’s commodity manufacturing can lock you out of tomorrow’s emerging industry,” he writes.

The same process is playing out today in future growth sectors like clean energy and nanotechnology. And that could mean that the billions the government is spending on research and technology could once again simply go toward enriching foreign manufacturers, says Liveris.

The way to turn things around, however, won’t involve implementing tariffs to bring back television assembly plants from Mexico. Liveris, who is a strong proponent of free trade, says it means—among other things— tweaking economic incentives in the United States to make sure that the manufacturing industries of the future can thrive.

“Other countries are offering loads of incentives because they recognize the value of high-tech manufacturing to their economy,” he says. “It’s actually less expensive for me to build a plant in Germany than it is for me to build a plant or factory in the United States. That’s astonishing.”

Already, Liveris is seeing things move in the right direction. “I think the administration is…trying to solve the problem,” he says, citing the President’s Jobs & Competitiveness Council, which met last week in North Carolina.

Former President Clinton agrees. In the cover story for Newsweek, he explains how a combination of state and federal incentives helped Nevada attract several thousand high-tech manufacturing jobs in the lead up to the 2010 congressional elections. Similar incentives convinced Siemens to expand its wind turbine factory in Fort Madison Iowa.

“We can…make a strong comeback,” Liveris says. “It’s not irreversible.”