Gmail can suggest responses to party invitations. Instagram can recommend emoji reactions. A forthcoming Google assistant will be able to call restaurants and make reservations in an eerily human voice.

And as computers learn to sound more like people, we’re starting to talk like computers.

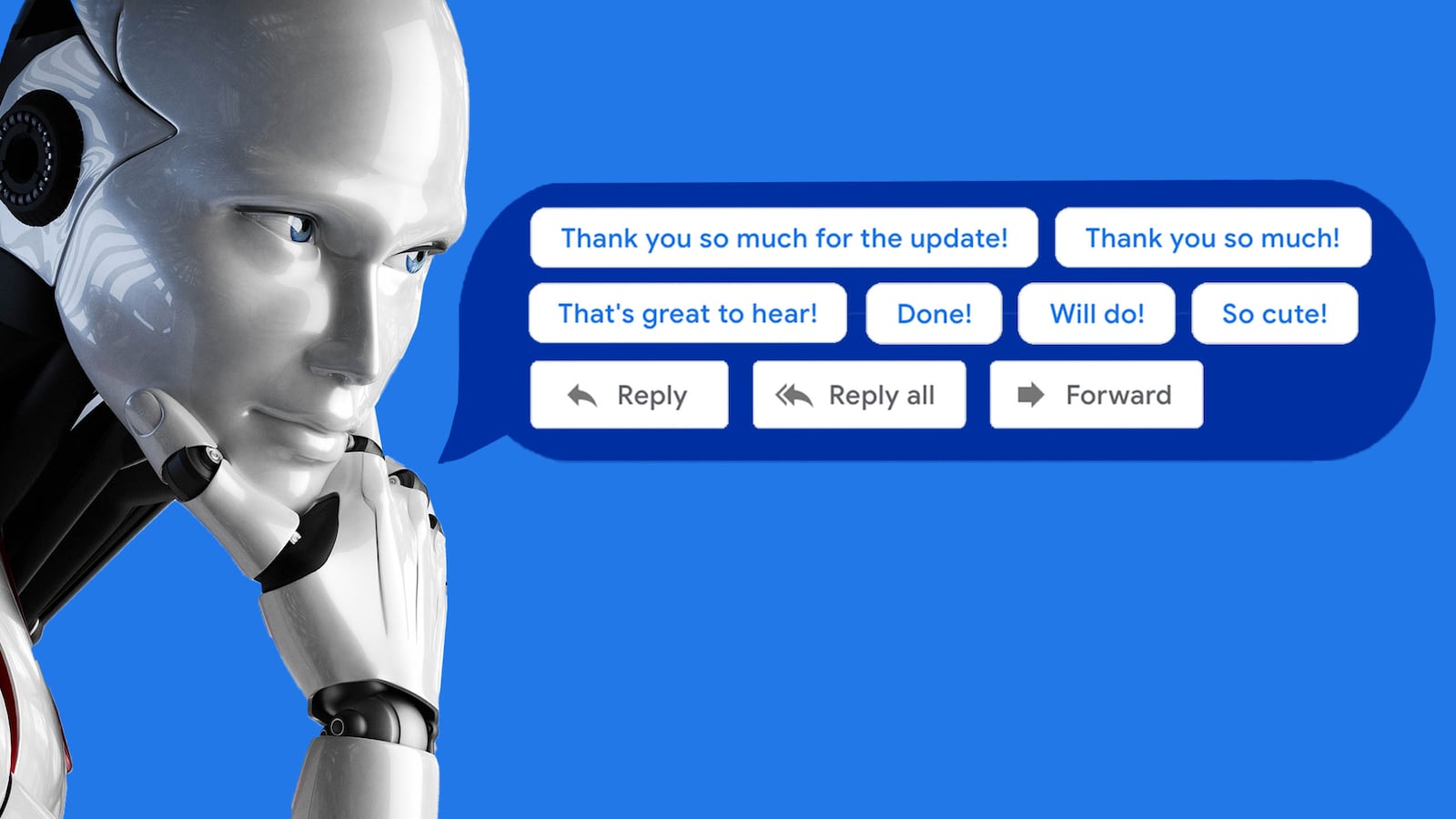

In 2018, Google, Microsoft, and Instagram have unveiled AI programs that mimic their users. Instagram rolled out a feature that suggests comments based on a user’s most-used emojis (the feature became default for all users in September). Google announced that it was testing its reservation-making voice assistant. Microsoft Outlook and Google’s Gmail rolled out their versions of “smart replies,” which analyze the content of an email and suggest short responses.

The programs are algorithmic approximations of us. And they might influence the way we communicate.

When a friend sent me a book club invitation last week, Google’s Smart Replies suggested three possible responses: “I’m in!” “Count me in!” and “Sorry, I can’t make it.” Instead of writing my own RSVP, I could simply click my preferred response and send it.

But even if I chose to write my own response, those suggestions might shape what I wrote.

Brian Green, director of technology ethics at Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, said he’d observed the phenomenon in his own work.

“I’ve noted this myself because we use a Gmail system here,” Green told The Daily Beast. “It suggests three things at the bottom of the email. I always look at them because they’re right there in front of you, if you want to click the reply button. I don’t click on any of them, but then I reply and feel like my thinking has been directed in order to answer in certain ways. I think it’s an interesting phenomenon in itself. It sort of psychologically suggests how you should respond to the person.”

Gretchen McCulloch, a linguist who specializes in the language of the internet, said she’d observed people changing their replies so as not to sound like the algorithm.

“I’ve heard from some people who say they deliberately avoid saying what’s in the suggested response to say they’re not like the machine, or ‘you’re not the boss of me,’” McCulloch told The Daily Beast.

New Yorker writer Rachel Syme described a similar phenomenon.

“Just as I decided that I’d thwart the machine mind by answering my messages with ‘Cool!’ [...] the service started offering me several ‘Cool’ varietals,” she wrote in an essay about the AI replies. “Suddenly, I could answer with ‘Sounds cool’ or ‘Cool, thanks’ or the dreaded ‘Cool, I’ll check it out!’”

Google’s artificial intelligence had detected a quirk in her writing habits, and distilled it into a single word that could fit over pre-written replies like “sounds good.”

No one, of course, is making you use the Smart Replies. They might even be useful for people in a hurry, people not fluent in English, or people who have limited access to a keyboard.

“Certainly for people who have trouble typing it could be helpful,” Green said. “It could help elderly people or people with disabilities communicate better.”

But using Smart Replies means using Google-approved language which, in the case of many replies, is chipper and heavy on exclamation points. The upbeat, affirmative tone and the mechanized answers can be helpful for work emails.

“In some circumstances, maybe in a work situation, suggested replies might make sense because there are a lot of canned responses you might need to use in a work environment,” Green said. “I think when you’re talking to family or friends, it’s not really appropriate to be mechanizing that kind of interpersonal interaction.”

We tend to send fewer non-work emails anyway, McCulloch said. “Email is sort of a workplace thing these days,” she said, adding that, through self-reinforcement, emails have mainstreamed business jargon like “circling back.”

The pre-programmed cheerfulness is also good for tech companies like Google, which want to generate a positive user experience and retain customers.

Companies like Facebook have previously struggled with how to portray negativity. For most of the social media giant’s existence, users could only respond to comments with “likes.” After years of users calling for a “dislike” button, Facebook partially caved and instituted “reactions.” Less ambiently negative than a “dislike,” the reactions let users respond to posts with specific emojis that represent “love,” “sad,” “wow,” “haha,” and “angry.”

In September, Instagram (owned by Facebook) rolled out its own version of smart replies: a series of “customized” emoji responses, supposedly based on emojis you frequently use on Instagram. Users can tap those emojis and leave them as comments on photos.

But the suggested Instagram emojis, while “customized,” are not your most-used emojis. On Instagram, my fourth recommended emoji is a big red heart, an emoji I seldom use and have likely never used on Instagram. On other apps that suggest frequently used emojis, my fourth recommended emoji is a knife. Instagram’s recommendations offer an Instagram-friendly interpretation of my typing habits, sterilized by some unknown algorithm.

“I’ve noticed it surfaces emojis I use a lot, along with generic positive ones,” McCulloch said, noting that Instagram’s recommendation algorithm “probably has safeguards against the gun emoji, even if someone types it a lot. I think it would be foolish not to have it.”

It’s possible to imagine a future in which our responses are guided or dictated wholesale by cheerful algorithms. People who use Google’s voice assistant to reserve a table at a restaurant will be deferring their decisions to a machine that always effects the same blandly pleasant tone, regardless of whether the restaurant places it on hold for an extended time. People who select the large red heart on Instagram will actually be selecting one of the site’s preferred emojis; if someone has never used an emoji on Instagram, the social media platform recommends them a selection of generic emojis, the first of which is the red heart, Mashable reported.

In an attempt to imagine how an all-AI language would look, I sent an email between my two Gmail accounts. “Can you write me back and tell me if it’s working?” I wrote. I committed to using Smart Replies for the rest of the conversation.

I replied to the first email with the recommended, “Yes, it is working,” and replied to that second email with the AI-suggested answer, “It’s working!”

This sent me into feedback loop with no apparent end, where “it’s working!” was the top recommendation for every email in the conversation. I switched between accounts and clicked the “it’s working!” button that invariably appeared at the bottom of each email. I did this 24 times until I gave up. The AI could keep happily working, probably forever, even if I couldn’t.

But would I start to sound like a machine if I relied on AI recommendations?

“I think it’s useful to acknowledge that this isn’t the first time we’ve got phrases from outside ourselves that we make part of our regular discourse,” McCulloch said, pointing to our repetition of phrases that appear in “greeting cards, song lyrics, proverbs … they’re not necessarily your words but you picked them.”