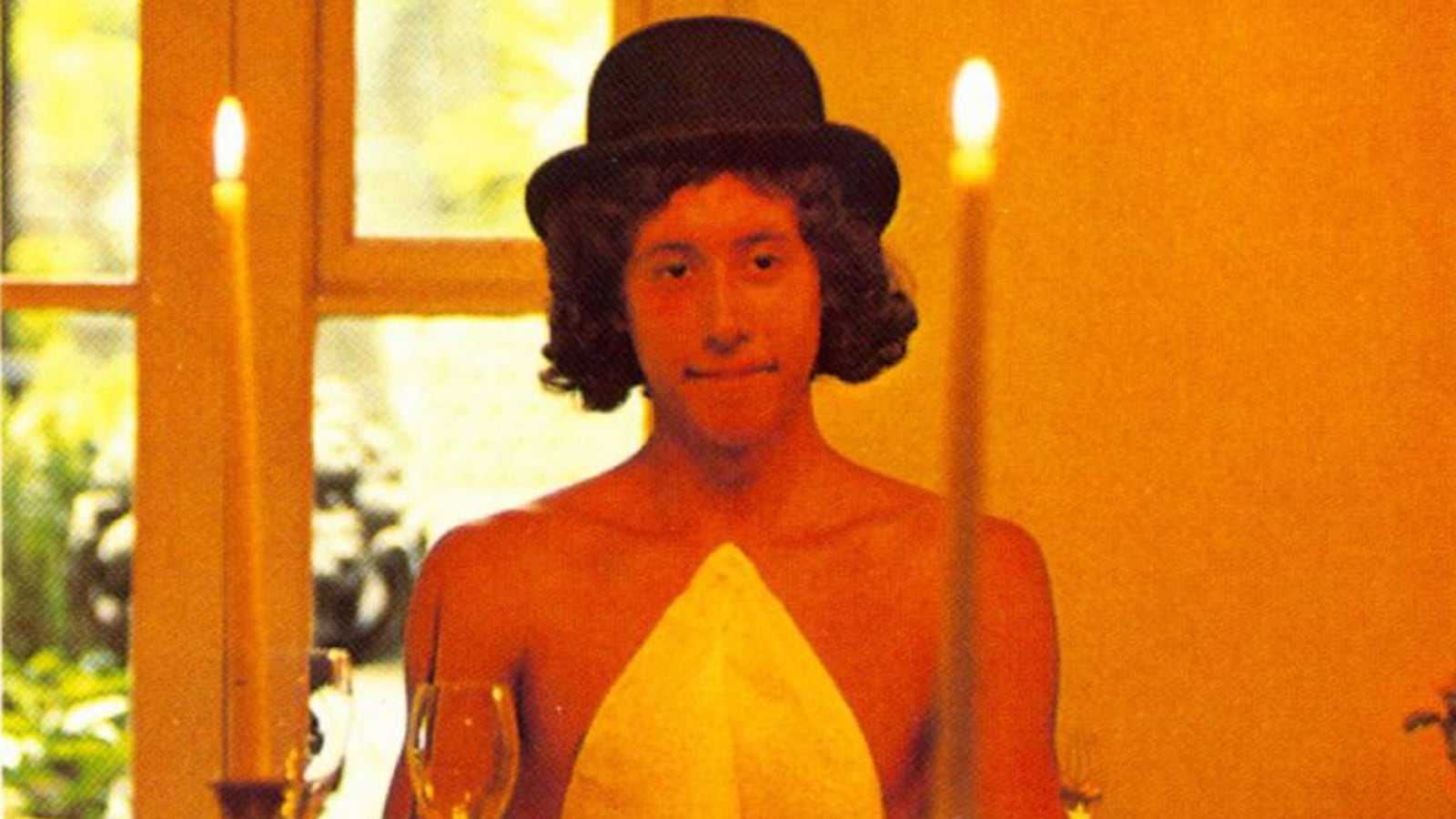

Fifty years ago, Arlo Guthrie took out the trash after Thanksgiving dinner. Little did he know the subsequent chain of events would lead to his most celebrated song, “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree”—an 18-minute deadpan-and-guitar monologue.

Every Thanksgiving Day for the past several decades, radio stations across the country play the slapstick story of Guthrie dumping trash at a popular cliff, getting arrested for littering the next day, and eventually being told he’s ineligible for the Vietnam War draft because of the citation.

“Alice’s Restaurant” has been made into a feature-length film, been used as an anti-war rallying cry (“[They] want to know if I’m moral enough to join the Army—burn women, kids, houses and villages—after bein’ a litterbug,” he snarks at the song’s climax), and launched the storied career of the son of legendary folk pioneer Woody Guthrie.

But the 68-year-old Arlo doesn’t like to play it live that often. He saves it for one year out of every decade.

And so 10 months ago, Guthrie and a small band set out on the road for his “‘Alice’s Restaurant’ 50th Anniversary Tour,” playing almost nightly to theaters across the country.

The set list obviously includes the epic title song, but is buttressed by lesser-known tracks from the eponymous LP, as well as his second-biggest classic folk song in “City of New Orleans.”

The Daily Beast spoke with Guthrie by phone about his unlikely classic, whether he’s really a counterculture icon, and how the story of pathetic politicians is increasingly relevant today.

You must be tired. Ten months on the road and counting. How’s the tour going so far?

Well, we started in January, so it’s coming up to a year now. And it’s been amazingly wonderful. It’s a lot different than previous tours in that there’s just a lot more to it, to each show. I didn’t know if that was going to be a pain in the butt or what. It’s turned out great so far.

Are you doing anything differently with the story this time around?

I have modified it to suit the times as best I could. But I don’t want to spoil too much. It’s been updated. But the trick is to keep the essence of the story so similar so that it doesn’t change all that much. I’ve changed the focus, but not the light.

You’ve described the song as a perfect “slapstick” comedy. It’s almost too good to be real, and yet you didn’t really embellish all that much, right? Most of this story actually happened to you, starting with Thanksgiving Day 1965.

Yep. The circumstances were so absurd that I discovered, by relating them, that everybody else just saw the absurdity. Some things are funny, and they are only funny to one or two people, but some other things are universally funny and the absurdity is one of them. The story is such a comedy of errors that are not on my part, really. I’m not the one that came up with the idea that I was unfit for military service because of a littering arrest. I didn’t make that up; I would’ve never thought of it. That came from the military [laughs]. So you just couldn’t make this stuff up. And I think people will always find that humorous.

How did it come about that you’d do a tour for the song every 10 years?

Well, going all the way back, I started writing the song in 1965. And by the early ’80s, I had been on the road with it for 15-20 years but things had changed: The war was over, our friends and neighbors were home, the draft was ended. The world had changed. So it became something that a lot of people expected to hear because it was nostalgic and it had been something at one time. I would call this the “Ricky Nelson syndrome.” He was a buddy of mine, and I was very sympathetic to his plight of having to feel like a trained seal performing the same tricks year after year, decade after decade. And I thought that I should retire it altogether and so I did somewhere probably in the very early ’80s. And people came to the shows, and I didn’t play it, and they demanded their refunds. And I said, “That’s OK! Give them the money back!”

I’m not going to get caught in that syndrome. I was writing new material. The world had changed enough for me to want to address what was going on at that time. And so I quit doing the song anyway. And I realized that we weren’t going to play the big theaters anymore. We would be back in the clubs. That was fine. But at the same time, I realized, for a lot of people, that song had become an emotional part of their history. I didn’t want to remove it completely, but I couldn’t do it every night either. And so I decided I’d take it out for a year or two, every decade. And so when the 30th anniversary came around, we did a tour of that. And when the 40th anniversary came around, we did a tour of that. And so here we are at the big 50th anniversary and we’re taking it out again.

And onward and upward to the 60th, too?

Well, if I’m around long enough to have to learn the whole thing again [chuckles] that would be pretty amazing. I don’t expect to. But I’m really happy that I could do this one because I’m still able to do what I do. I realize I’m on the downhill side of my career in terms of ability. The older you get, your voice gets a little weaker, your fingers don’t play quite like they used to. And I felt that way a couple years ago, but I felt, “Well, it’s still good enough.” So this is the perfect time to do this before I run into memory problems and arthritis and whatever else happens to you.

Music writers often label the song “anti-war,” but you’ve recently suggested it’s not expressly anti-war. It’s about something bigger?

Originally the events unfolded pretty much as the song relates; I didn’t have to do too much. There’s not a whole lot of poetic license. I did change a few little things that were relatively unimportant to the story. But people’s take on it, what they called it, really had more to do with them than what it was. You know, we sold as many records of “Alice’s Restaurant” through the PX [U.S. Army’s Post Exchange] as we did in record stores. It was the military guys that loved it. Those guys that were in Vietnam were playing it over there, laughing their butts off—because they had gone through it. They knew I wasn’t making it up. To other people, it was Arlo commenting on stuff. But I wasn’t really commenting at all. I was just relating what happened to me. So in that sense it certainly wasn’t an anti-war song as much as an anti-stupid song.

Don’t mistake where I was, though. I was an anti-war person. At that time and in that era, I was totally opposed to the war in Vietnam. So it’s easy to make the conclusion that because he’s an anti-war guy that’s an anti-war song. I don’t get upset about whatever people want to call it. But to me, it was just me telling people what had happened to me, because I knew in some way it had happened to everybody. If it didn’t happen to me under those circumstances, it happens to other people in different circumstances. That’s what keeps the song going.

And the song describes these bumbling bureaucrats and the dickish draft board. Do you see that still being relevant today?

I think stupid people are easily tolerated in this world. For good reason. We’re all stupid at times. However, having said that, when political leaders are stupid and their supporters are stupid, we get into especially stupid situations. For us, as Americans, you don’t have to think very far back. As far as I’m concerned, getting into Iraq was stupid. And I think the guys who are in the Middle East creating all the havoc, they are stupid. Their leaders and the people that support them are just plain stupid. We might be stupid in different ways, but it’s important to realize that just because people in positions of authority are stupid, it doesn’t mean you have to go along with it. When you encourage people to not go along with it, the world becomes a lot more fun for everyone.

So you’re staunchly anti-stupid.

There’s stupid on all sides. It’s part of being human. I’ve been stupid. But I’ve never invaded somebody else’s country. I’m not that stupid. So I think we have to look into it a little more to understand when stupid begins to hurt other people, when it begins to get us into situations that we’d rather not be in. Then I think we have an obligation to stand up and say something. I’ve never shied away from it. People may disagree, that’s fine. But I’m a firm believer that when enough people voice their opinions, we generally avoid the critically stupid stuff. It doesn’t mean that every time in history that’s been the case, but for the most part it’s been the case.

Speaking of being politically vocal: In 2012, you were a big Ron Paul supporter. What do you make of the current landscape?

As you can imagine, I took a lot of flak from a lot of people, but I still stand by what I said back then, which was: Ron Paul was one of the few voices back then, at least on that side of the aisle, that was opposed to our adventurism in the Middle East. And that doesn’t negate every stupid thing he might’ve said. Nobody’s immune. There were things I agreed with, and things I did not. I felt the need to support him for that view at that time. And I would do it again.

Who do you like now that he’s not running for 2016?

Now we find ourselves in a completely different world. I love Bernie Sanders, naturally. Who wouldn’t? But I don’t agree with him on everything. To be honest, what I do is I take a longer view. I know that it doesn’t matter as much who the president is as who the people feel they are. That’s what really changes the world. If we’re waiting for some guy or gal to fix everything, that’s a fool’s errand. I think it’s really important for people to do what they can, where they are, in their own hometowns and if it seems like a good idea, you’ll get some support. That’s how I think the world evolves. It does not evolve dependent on leaders.

I take that seriously. That was the main message my father had for the people he wrote for: Take yourself seriously. You count. And when I see people in positions of authority trying to silence the voice of others, I get pissed off. The world really does require us to pay attention. Sure, there are natural ebbs and flows to the rivers of evolution—sometimes it’s gonna go left, sometimes right. No river runs straight down. So when somebody promises you a straight path, look out.

Sounds like you’re unhappy with our two-party system?

I am equally suspicious of Democrats as I am of Republicans. I don’t think either party has a handle on honesty at this point, and that’s a shame. And that’s because we don’t look for that as a people. People seem to just look to get fired up, and feel like a bunch of yahoos. That works in the short run, it makes you feel good. But in the long run, it’s a disaster.

Are you describing the phenomenon that is Donald Trump’s popularity?

Oh, he’s not the only one. Everybody does it to some extent. By the way, the wonderful thing about Donald Trump is that he’s not in anyone’s pocket. But, of course, that doesn’t mean he has the best interests of everybody in mind. The phenomenon of it is funny, scary at times, and that’s as it should be. But I think in the long run, no matter who the president is, there’s only one of him, and there’s hundreds of millions of us. So what we believe, and what we stand for, and what we think, and what we actually do will count for more, in the long run, than whoever the president is. The kind of problems we have are genuinely systemic. This bought-and-sold-ness of politicians and leaders goes all the way down to the local level. It goes down to who is the judge, who gets voted in for the sanitation department head, or whatever. When people profit at the expense of the best well-being for everybody, it’s not a good situation. And I think that’s what people feel.

There does seem to be a great deal of disillusionment with politics these days...

It’s like it’s almost a lost cause. And, of course, being me, I know it’s not. We’ll get through it. It might be rough, and history will continue to be made, and it’ll just be a different time. I think young people are perfectly capable of handling this. This is not my world anymore. It belongs to people much younger than I. And honestly, I think they’re doing a good job, for the most part.

You have to understand that what changed in the ’60s was not the result of most people doing anything. It wasn’t even a whole lot of people. It was a critical mass. We as messengers of ideas have to remember: You don’t need to convince everybody. You don’t need to convince a lot of people, just enough people. When you have enough people to move the world forward, it will move.