Yeehaw! We done struck crude down alongside Times Square! But the energy we’re pulling from it is entirely artistic.

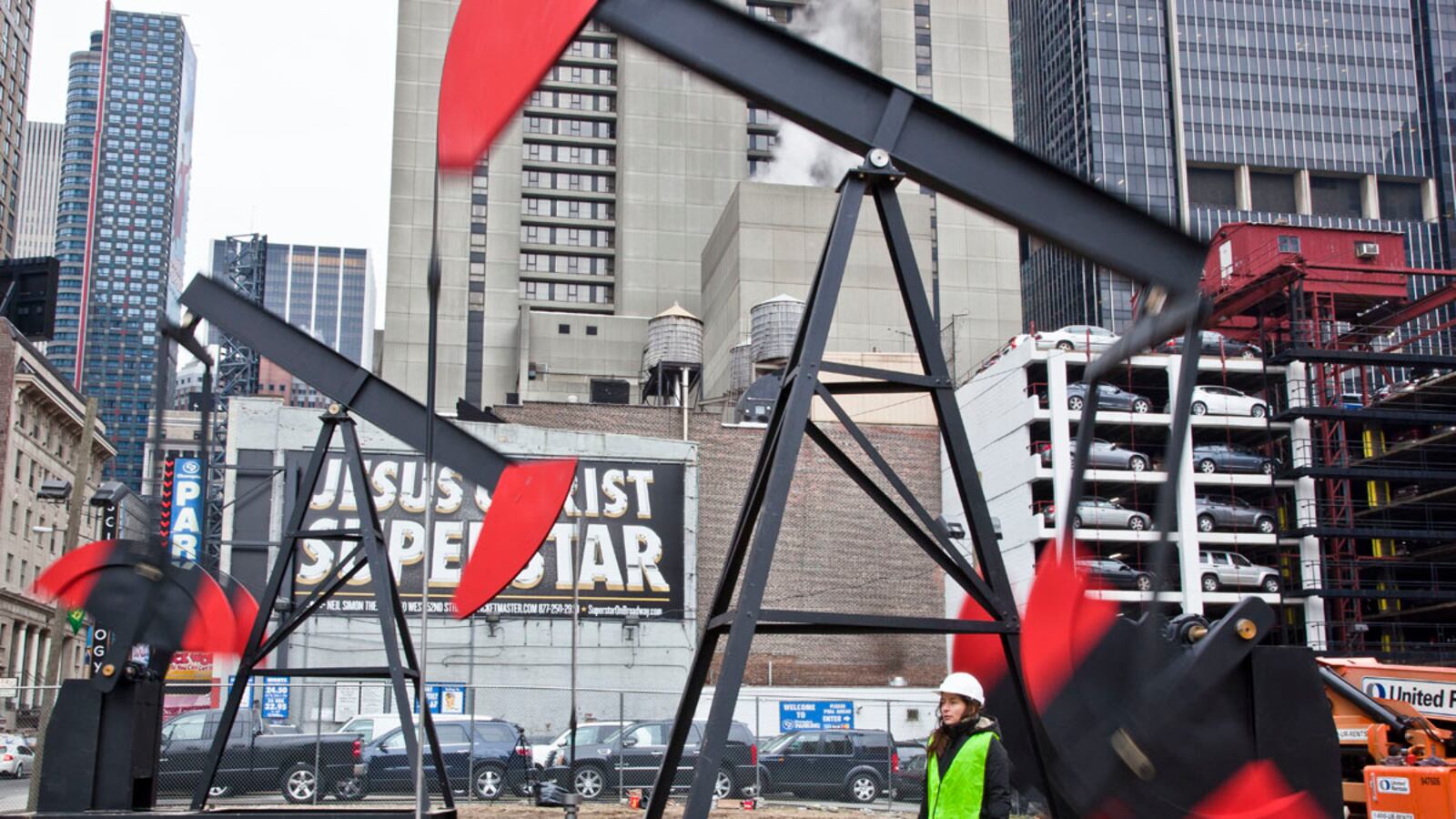

In a muddy lot at the foot of Restaurant Row, flanked by touts for tour buses as well as a Broadway theater running Gershwin and a gimcrack Irish bar, two archetypal oil pumps are doing their thing, nose to the ground and then up in the air, hour after hour after hour, as though a Texas oilfield had settled for a spell in New York.

“Most people assume that it’s some kind of construction site or a real oil facility,” says Josephine Meckseper, the German-born New Yorker who has installed the pumps as her first piece of public art, officially unveiling Monday March 5. Not that she’d prefer this piece to be shown anywhere else: exhibiting outside, she says, in such an untended spot, leaves more room for ambiguity than the many museums she’s shown in. “There is nothing worse than people getting off a Greyhound bus, and being presented with a pretentious art work.”

At 47, Meckseper is a notable presence on the international scene, famous for her peculiar mashups of consumer bling and protest culture. A classic Meckseper installation might include a vitrine showcasing sparkly bits of Mylar and cut plastic, with echoes of an H&M window, paired with abstraction built on a kaffiyeh scarf and maybe video of a political march. I first profiled Meckseper eight years ago, when she was just hitting her stride, and she had a vibrant, hipster-cool edge. Since then, both she and her art have matured and settled down. She’s still a striking woman, but now, with her long hair worn pulled back from her face, she’s got an almost pre-Raphaelite poise. And, in her art, the new pump-jacks have a spare directness I’ve never seen her achieve.

“I really wanted to make works that reflected a sense of reality,” she says—works, that is, in stark contrast to the “simulacra” provided by the corporate culture of nearby Times Square. “Our society and our culture is really defined by the pathology of consumerism, and wasting energy. There’s no clearer picture of the excess of our consumer culture than Times Square, and how it’s being used to distract people from real issues.” How many city squares on the planet actually demand that store signs throw out far more light than they could possibly need to attract a buyer’s attention?

Thanks to Meckseper’s piece, the energy being wasted in midtown Manhattan will come up hard against the heavy industry that provides it. A Meckseper pump is “99 percent” like the real thing, she says. She actually made a trip to the town of Electra, long known as the “pump-jack capital of Texas,” to get a look at the machines in operation, then designed her own version to be “the summary of the most generic oil pump-jacks. It represents the average height and shape of the pumps.” And rather than go to some fancy art-world fabricator “who would have made it into a precious sculpture”—the pieces already have echoes of Alexander Calder and Mark di Suvero—she had each of her pumps built by a regular metal-working shop in New Jersey that also does work for the public utilities. (Some modifications had to be made to allow for the fact that Meckseper couldn’t actually drill a well into a New York lot, and that no oil would be coming out of the ground.) Meckseper’s “Manhattan Oil Project” was organized and funded by a New York nonprofit called the Art Production Fund, for an unbuilt parcel of land lent by the Shubert Organization, the great Broadway impresarios. The pumps will run weekday mornings and evenings, and for a straight nine hours on Saturdays and Sundays.

There’s a beautiful surrealism in Meckseper’s collision of urban New York with rural Texas—but it’s a surrealism that feels natural, not like the contrived artiness of melting watches or a lobster telephone. And Meckseper hopes its incongruity will wake us up to the incongruity of a postmodern, virtualized, 21st-century world that’s still powered by what is basically steam-punk technology. “I really do think that when you look at these oil pumps, they look very anachronistic, from the 20th century ... You look at them and feel that it’s really time to put them behind glass in a museum, and move on to where European countries have gone, to wind and other clean energy.”

But the project is not meant as a Green Party screed. “I’m not out to lecture people. I want them to come to their own conclusions,” says Meckseper, adding that there will only be a minimal sign announcing her piece, camouflaged as “a generic construction-site information board” and with no extended explanation.

“Everyone has a different response to these things,”she says. “New York being fairly liberal, there will be a lot of people opposed to fracking, and drilling.” But as she stands by the relentlessly pumping machines, a passerby screams “Drill baby, drill”, and Meckseper recognizes that her piece could also read as a Republican, pro-oil symbol.

Meckseper points to the “cowboy charisma” of her handsome pumps, and she’s right. They hold the space they’re in better than just about any public sculpture I’ve seen—as far from “plop art” as could be—and give a real thrill as you walk by them. Meckseper’s heavy-metal parts swoop up and down with a combination of control and abandon that makes me think of kids sweeping high on swings in a park. They have a weirdly jubilant streak that defuses any hint of a Luddite subtext. Meckseper says her artist father was a fan of 19th-century technology; she remembers when he put an actual steam train on tracks through the German village she grew up in. She acknowledges that she’s inherited his taste. “If I’d had time, I would probably have studied engineering, because I’m really fascinated by it. I’m always the one who fixes things around the home.”