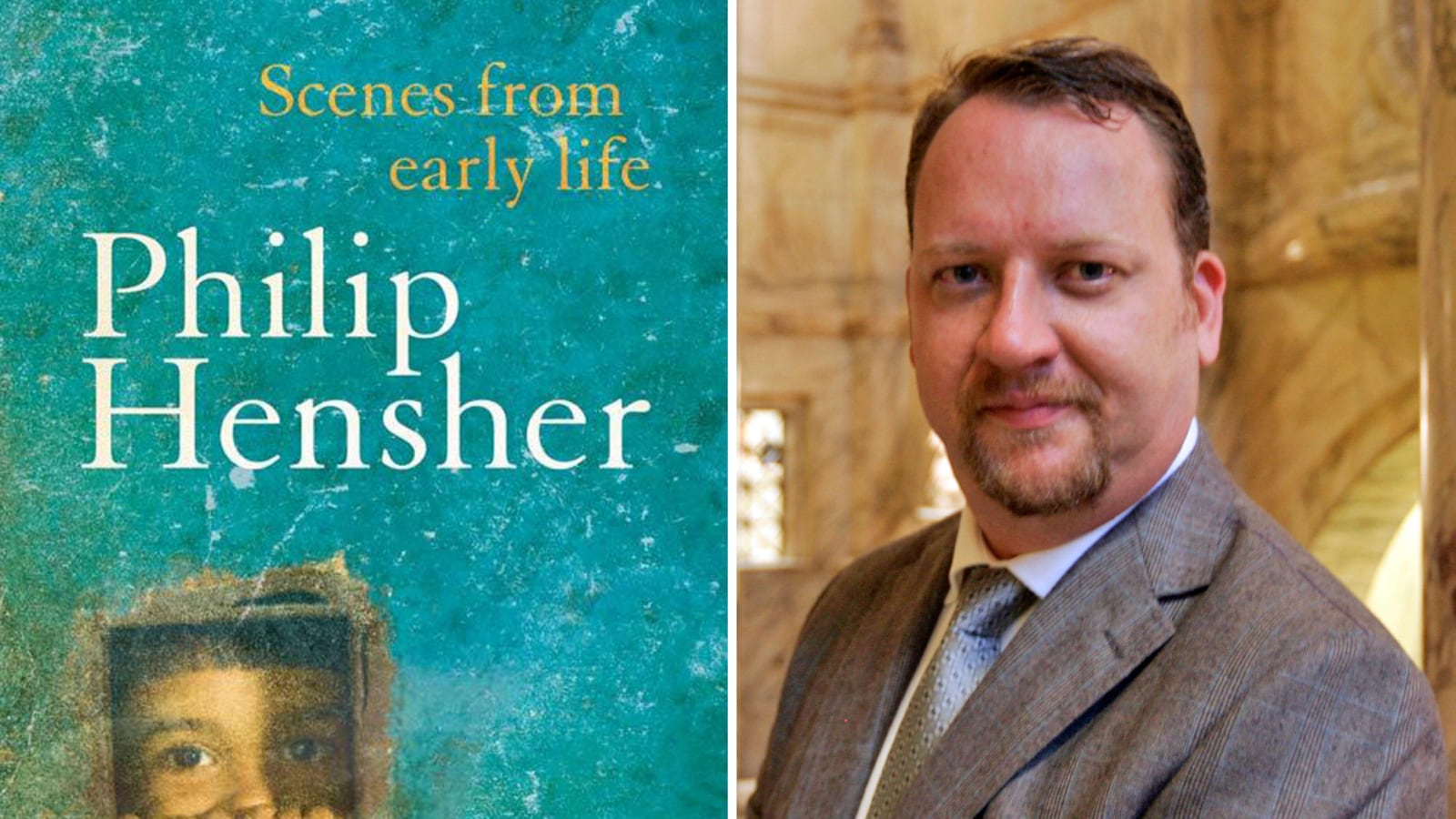

“Anyone who attempts to relate his life loses himself in the immediate,” said the Paraguayan novelist and short-story writer Augusto Bastos. “One can only speak of another.” It’s a sentiment that British critic and novelist Philip Hensher takes seriously in his new book. Scenes From Early Life is a story twice removed. It is a novel told in the form of memoir, in which the narrator speaks in the voice of Hensher’s husband, Bengali-born Zaved Mahmood. On a purely practical level this act of ventriloquism can be explained by the fact that Zaved, a U.N. human-rights lawyer, was never going to find the time to write his own story, but it also declaims the novelist as the heir to Gertrude Stein, whose then genre-defying The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (Toklas was Stein's lover and companion) was published in 1933.

Scenes From Early Life opens in mid-1970s Dhaka, where, despite his tender years, Saadi (Zaved’s fictionalized name) is well aware that there are children whose parents had taken money from the Pakistanis during the Bangladesh Liberation War—they are children “you weren’t supposed to play with.” “It was as if there were two cities laid on top of one another,” the narrator recounts. “Each quite invisible to the other, each engaging only with its own sort.”

Like Saleem Sinai, the narrator of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, who was born at the stroke of midnight that signaled India’s independence, so too Saadi’s birth in 1970, into a troubled country on the eve of its liberation, heralds something of a new beginning. “Pakistan was a single nation, but anyone could see that it was split in two. To the left was West Pakistan, where they ruled, and spoke Urdu, and wrote in an alphabet that flowed like water under wind. To the right was East Pakistan, where the Bengalis lived. They spoke Bengali, which chatters like a falling xylophone, and is written in an alphabet that looks like a madman trying to remember a table’s shape.”

Scenes From Early Life is part novel, part memoir, and part history. Hensher doesn’t attempt to provide a full historical account of the 1971 war. Rather, he tells the story of Saadi’s experience of it. Saadi’s upper-middle-class family is one that has a great respect for culture, where music teachers were treated “as honored guests” and not as servants or tutors. Music, poetry, and art are more than just adornments, particularly in 1960s East Pakistan, where the enjoyment and encouragement of these “statements of Bengal nationhood” become nothing short of a patriotic duty as a response to the government’s systematic suppression.

Those who organize small social gatherings find themselves accused of holding anti-government meetings. Saadi’s neighbor Sheikh Mujib is as likely to be found in jail on trumped-up charges as he was to be “visiting his old friends, and drinking tea.” A Hindu tabla player named Amit, who teaches music to Saadi’s aunt, is hounded out of his job at a local school and forced to flee to India.

Baby Saadi was kept quiet with constant feeding, lest his cries should alert the attentions of the soldiers patrolling the streets. This produced a “gargantuan” infant, his eyes “deeply buried in fat rolls of cheek, like currents in a bun.” His every need was anticipated by a bevy of aunts at his constant beck and call. As such, the most traumatic memory in Saadi’s young memory is that of the day his beloved pet chicken was served up as dinner, but this is juxtaposed against the knowledge that just a few years earlier, a family living no more than a few houses away was butchered in its entirety by Pakistani soldiers—the men were shot; the women were raped and beaten before they met the same fate; a baby’s throat was cut with a kitchen knife in order not to “waste a bullet.”

Although the central consciousness in the novel is Saadi’s, this is, as Hensher points out in his author’s note at the end, the story of a family. Some of the “scenes” take place long before Saadi’s birth, before his parents are even married. But the whole that slowly emerges is a perfect tessellation of oft-repeated family tales. There are constant reminiscences of the dishes they ate while trapped in their home the summer that the “violence and terror washed up against the gate of the house.” It is Hensher’s astute understanding of how such stories bind families together that reinforces this work against accusations of literary colonialism. Hensher’s appropriation of his husband’s voice is just another example of how family lore, once taken root, spreads its branches through each and every generation—even across bloodlines and into the consciousness of an English novelist.