Basquiat’s Close Friends and Collaborators Speak Out Against Jay-Z and Beyoncé’s Tiffany’s Ad

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast / Photo Mason Poole for TIffany & Co

“People think that his association with luxury was because he was impressed with that shit, but he couldn’t care less,” pal Al Diaz explains.

In the last week, the art world has become obsessed with a particular shade of blue. A new Tiffany & Co. ad campaign announcing a collaboration with Jay Z and Beyoncé, foregrounding a never-before-exhibited painting by the late Jean-Michel Basquiat entitled Equals Pi, has come under heavy scrutiny by artists and curators alike. Tiffany’s now owns the portrait, rationalizing the purchase and its commercial use by emphasizing Basquiat’s affinity for the company’s statement blue color. “As you can see,” executive vice president of product and communications Alexandre Arnault told WWD at launch, “there is zero Tiffany blue in the campaign other than the painting. It’s a way to modernize Tiffany blue.”

There are a host of reasons why the new campaign has onlookers giving the announcement a proverbial and literal side-eye. From the annoying “first ever Black (insert here)” tokenism of Beyoncé’s donning the famous 128.54-carat Tiffany Diamond (a blood diamond that has been labeled a “symbol of colonialism” in, of all places, The Washington Post) that only Audrey Hepburn and Lady Gaga have had the privilege to wear since it was “unearthed” in 1870s South Africa, to the strange yet telling $2 million tax write-off given to HBCUs to smooth over the problematics. But, it is still the art, specifically the “robin egg” blue, that has prompted many questions regarding artistic intent and the commercialization of image.

For close friends of Basquiat’s who lived and worked with the late, trailblazing artist in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the answer is quite clear: Their loved one was not thinking about Tiffany’s at all while conjuring Equals Pi.

“I’d seen the ad a couple days ago and I was horrified,” Alexis Adler tells The Daily Beast. Adler, who lived with Basquiat in his earlier years of art-making between 1979-1980, maintains that “the commercialization and commodification of Jean and his art at this point—it’s really not what Jean was about.”

At first glance, it might seem like the function of the ad, to sell a more modern Tiffany & Co. to their wealthy consumer base, might align with Basquiat’s desire to sell his art at a high price, but where his art was displayed mattered more so than the monetary transaction itself. “Unfortunately, the museums came to Jean’s art late, so most of his art is in private hands and people don’t get to see that art except for the shows. Why show it as a prop to an ad?” asks Adler. “Loan it out to a museum. In a time where there were very few Black artists represented in Western museums, that was his goal: to get to a museum.”

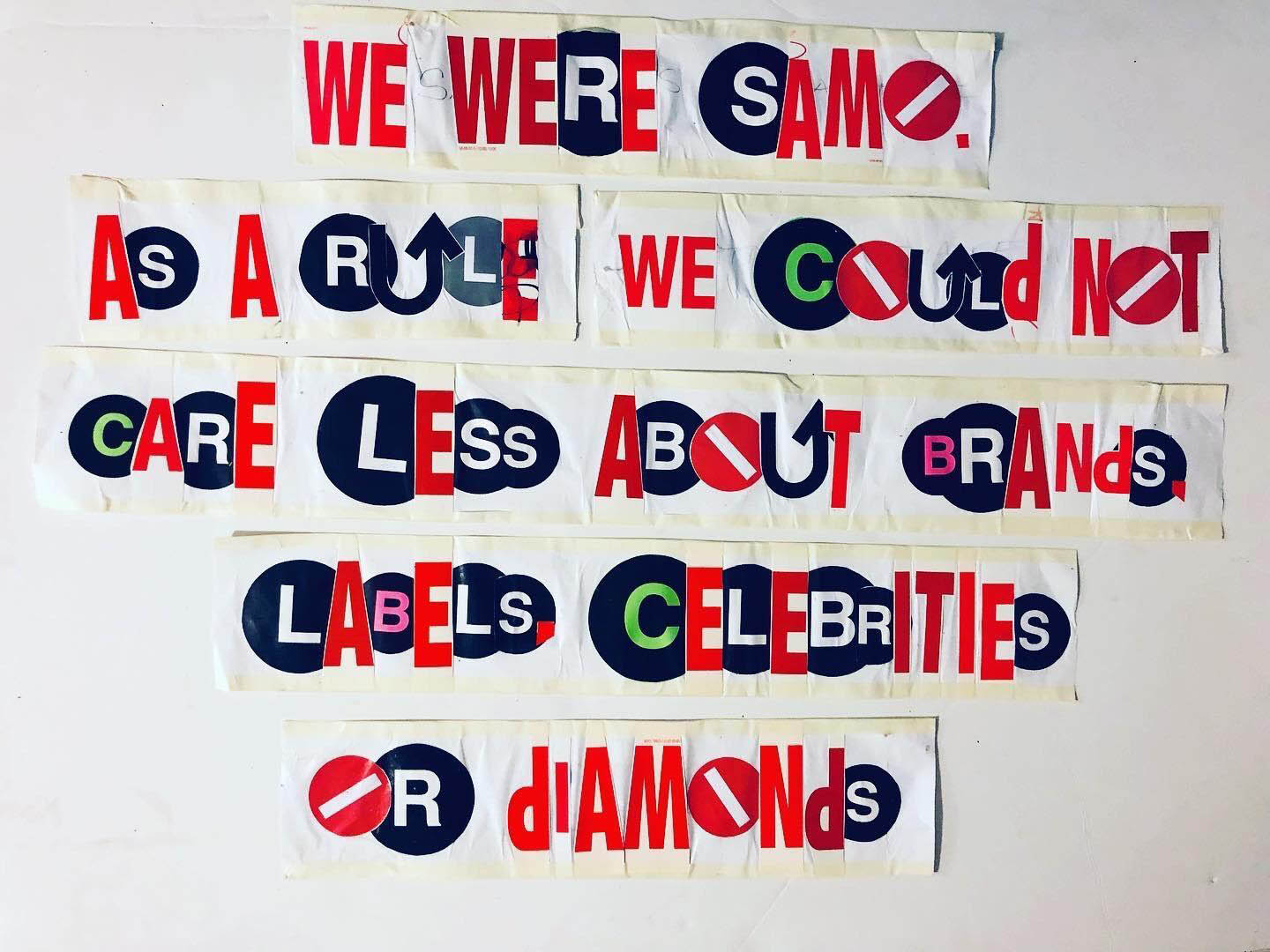

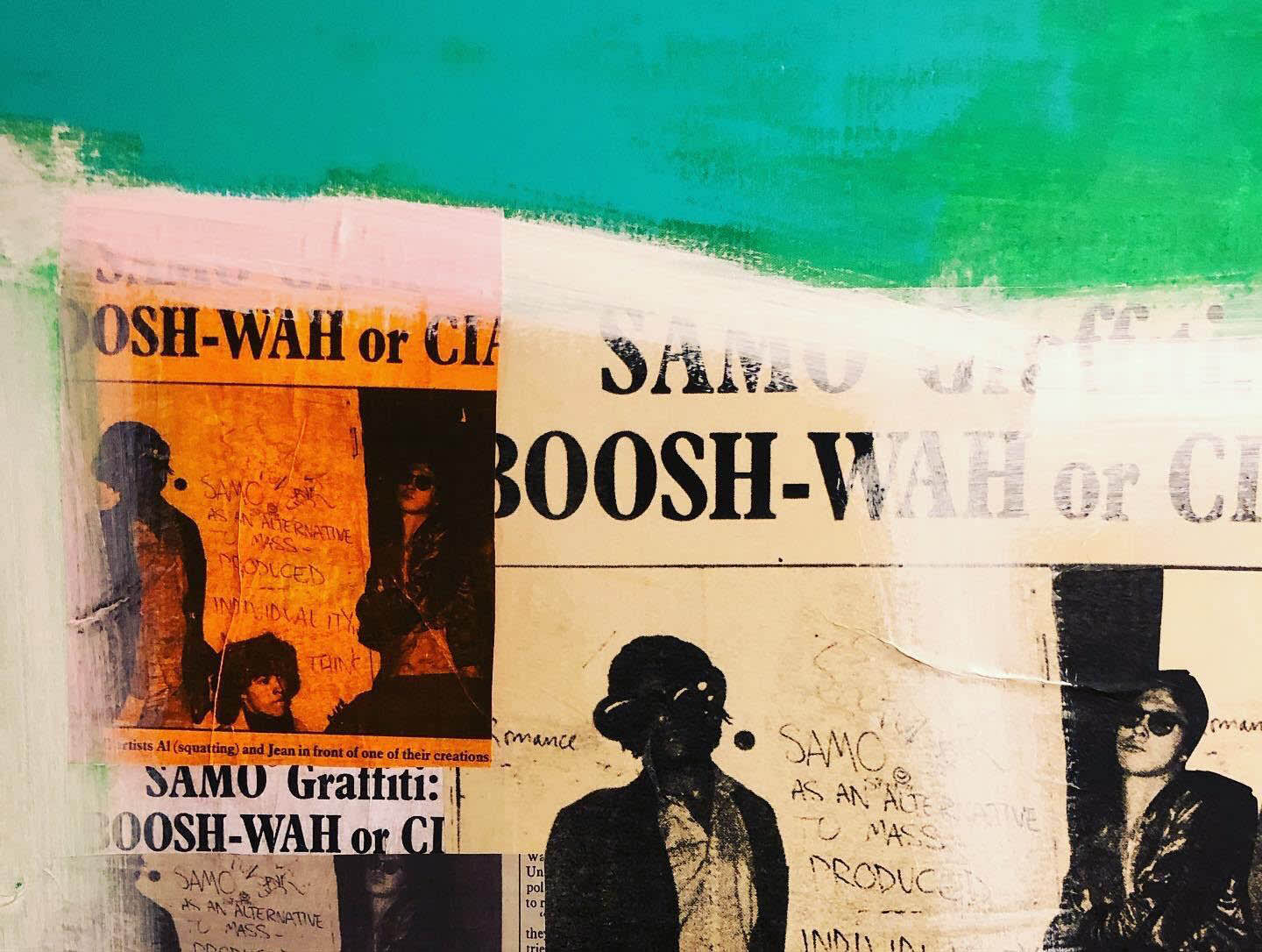

The fact that Equals Pi will permanently hang on the walls of Tiffany’s flagship boutique on Fifth Avenue proves a sore spot for artists like Al Diaz—who was a close friend of Basquiat’s and collaborated with him as a teenager on their street art duo SAMO—and Stephen Torton, who mixed paints, framed hundreds of Basquiat’s paintings, and worked as his assistant for many years. “People think that his association with luxury was because he was impressed with that shit, but he couldn’t care less,” Diaz explains. “It’s not just about wearing an Armani suit. If he wore it, it’s because he could buy it and fuck it up, it wasn’t because the stitches were fabulous or well-made.”

Courtesy Al Diaz

But what’s happened in the last decade or so, as images of both Basquiat the face and Basquiat the aesthetic swarm brands like Avian, Urban Decay and Coach, is an overemphasis on the more lurid aspects of his biography—the party animal, the fashionisto, the drug addict—and a flattening of the art itself. “It’s lost in translation,” Diaz remarks, exasperated. “People won’t see the depth. At this point the only people that could afford a Basquiat are people he was targeting. Like, you’re the oppressor. They buy it out so that it becomes meaningless.”

Torton first took to social media to dispel the notion that Basquiat was imagining the Tiffany blue when he made any of his art. “I designed and built stretchers, painted backgrounds, glued drawings down on canvas, chauffeured, travelled extensively, spoke freely about many topics and worked endless hours side by side in silence,” he asserts via Instagram. “The idea that this blue background, which I mixed and applied was in any way related to Tiffany Blue is so absurd that at first I chose not to comment. But this very perverse appropriation of the artist’s inspiration is just too much.” And, while publications like The New York Times earlier this week featured comments from art dealer Larry Gagosian claiming he’d never heard of Torton, when The Daily Beast began reaching out to friends, collaborators and curators, each of them mentioned Torton by name as someone who’d know best about Basquiat’s color-mixing.

For Torton, the public interrogations surrounding the color are a calculated move by Tiffany & Co. to heighten interest. “They know damn well where to find answers to the questions,” Torton exclaims to The Daily Beast. “When they write books about his influences: [the 20th century Austrian expressionist] Egon Schiele, or African art, or his interest in voodoo, they call me up asking: ‘Was he aware of this? Was he interested in that?’ They know where to find the answers to the questions. They’re not interested in the truth, it’s not like they made a mistake.”

Torton and Basquiat’s contemporaries believe the questions alone fuel interest, not the reality. But without the truth, it’s hard to imagine that Tiffany & Co. have much respect for his art or life. “They wouldn’t have let Jean-Michel into a Tiffany’s if he wanted to use the bathroom, or, if he went to buy an engagement ring and pulled a wad of cash out of his pocket. We couldn’t even get a cab,” Torton says.

Curators within the art world are also adamant that the blue had no connection to Tiffany’s in its original conception. Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one longtime curator of Basquiat’s paintings offers, “Let’s say he did reference that color on purpose—which seems out of character for him to do something that simple—I think it really flattens his artistic approach. He was a really deep thinker. His work wasn’t like, this symbolizes this. Everything references something but then it tells a story of that thing. But let’s say he did though… to use it in an ad, it wouldn’t have been the context. It wouldn’t be used to sell Tiffany’s but to say something critical, maybe about blood diamond-extraction or something. I just think it’s a reach.”

In trying to determine what exactly the blue could be referencing, it’s also important to note just how often Basquiat used that shade in other works. Chaédria LaBouvier, one of the foremost Basquiat curators in the world whose recent Defacement exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum was widely considered a seminal showcase of the artist’s most urgent work and political themes, writes via email: “Photography, age and protective glass covering can change how the color looks to the eye, especially for Basquiat’s works, because many of the early works are not primed and a lot of his works are not glazed, or with a glass covering. The robin’s egg blue in Equals Pi and colors very similar to it show up in few other works, particularly in his early period from about 1980-1983, in which Equals Pi was also created. You can see the picture peeking through In Italian, it makes an appearance in Untitled (History of the Black People) and Six Crimee, and seems like a monochromatic meditation in acrylic and oil stick.”

As much as Tiffany’s would like to take credit for the blue used here—which wasn’t trademarked until 1998, long after Basquiat’s passing—it doesn’t bear any actual weight, according to his friends and experts. What the ad and other commercialization efforts do is, perhaps, shroud Basquiat’s work in a mystique that belies the artist’s desires. There is little doubt that he didn’t want his art explained, given his famous saying: “It’s like asking Miles, ‘How does your horn sound?’” But as Torton tells us, “I don’t know the truth but I know a lie when I see one.”

Six Crimee by Jean-Michel Basquiat

The Museum of Contemporary Art

The true tragedy of this flattening of Basquiat’s style, image, and interpretive power is the potential impact it has on further scholarship of his work and his life. There are signals through stories of his life and how he handled consumerism that unlock his perspective. The hearty laugh Diaz loosens from his chest when describing how he and Basquiat once rolled up to “a fancy West Broadway boutique when there were very few fancy boutiques on West Broadway” in coats wielding seltzer bottles like machine guns and opening fire on all the “feathery” merchandise spoke to his opposition of crass materialism. Or, the time he defended Alexis Adler and mutual friend Felice Rosser from some “rough characters,” giving them hell outside a club, the first time they ever met him.

You can hear the same respect and trickster-god awe from Torton when he describes Basquiat’s subverting of race and class stereotypes when dealing with dealers. “The idea of having an underappreciated white assistant was very much a Basquiat invention, he was very conscious of it. We played it to the tee. I had a tie on, so I look like a businessman or a lawyer to a lot of people, and he’d set people up who were trying to make a business deal with him. He’d be like, What are you going to my assistant for? Like, if I was white and he was Black you wouldn’t do that. It was so calculated that it was painful,” he laughs. “And we’d give each other high-fives. It was vicious.”

Courtesy Al Diaz

It’s this, the spirit of who Jean-Michel was to his friends, the love, interlocking meanings and messages, and the agency he wielded when producing art, that they feel is lost most. There are some things that ads for 1800 Tequila, Reebok shoes, and Coach bags just won’t capture. Though many of his paintings will be hung on the walls of fancy businesses and academic institutions that most interested parties won’t be able to see, the art itself still holds an indelible spirit and power divorced from the machinations of capital.

There was a moment in 2012 when Adler realized just what was attracting new generations to Basquiat, during a seminar at The New School on Basquiat’s work. “The room is packed with young people hungry for information. Al Diaz and Michael Holman, both good friends of mine, were all on the panel. They called on me to address questions and everything. And then afterwards I realized, oh my gosh, all these people want to know more about Jean. The museums and the art world were aware of him but now this cultural icon has come to the fore and people are appreciating him and that’s cool. [The merch], I don’t believe that’s what’s fueling the interest in Jean-Michel Basquiat. The seminar happened before all the merch. People are interested in his art and what it says to them. It speaks to them. And that’s where Jean is communicating. He’s not doing it through the merch.”