In the days of ancient Greece, when city-states were constantly at each other's throats, the Olympic Games were said to bring peace. As the story goes, the ancient tournament occasioned a truce where Athens, Sparta, and the rest would pause from decapitating and doing war to sit down for a nice naked race, a lively round of pankration, or a ritual sacrifice of 100 bulls on the Great Altar of Zeus.

Like most Olympic legends, however, the truce was mostly myth, born long after the ancient games ended. In truth, there was a peace agreement, but it didn’t amount to much. The ancient Olympics were rife with scandal, bribery, doping, and outright war. In one particularly unfortunate incident, invaders crashed the final event of the pentathlon and turned a wrestling match into a battlefield, with rooftop archers and 5,000 troops clashing in hand-to-hand combat. By A.D. 393, the Games were abolished for corruption.

The myth of the Olympic truce lasted well into modernity. The Games were revived in 1896, when Greek poet Panagiotis Soutsos published a poem called “Dialogue With the Dead,” calling on his country to bring back the competition as a way to restore national pride. Over the past 123 years, they have operated in a similar mode: hailed as a kind of global team-building exercise—encouraging unity where there might otherwise be strife; celebrating gold and silver rather than killing for them.

For a brief moment in 2018, for example, some posited the PyeongChang Games could dissolve the conflict between North and South Korea. And organizers for the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo dubbed it the “Recovery Games,” claiming the competition’s resources would help Japan recover from the 2011 earthquake and the fallout of Fukushima. Neither prediction bore out—the DMZ is still lined by guards and some of the 2020 competition will take place in areas highly contaminated by nuclear waste. The irony of the Olympic truce myth may be best illustrated by a June op-ed in the Los Angeles Times: “For a more peaceful vision of the future, look to the Olympics.” The author was Henry Kissinger.

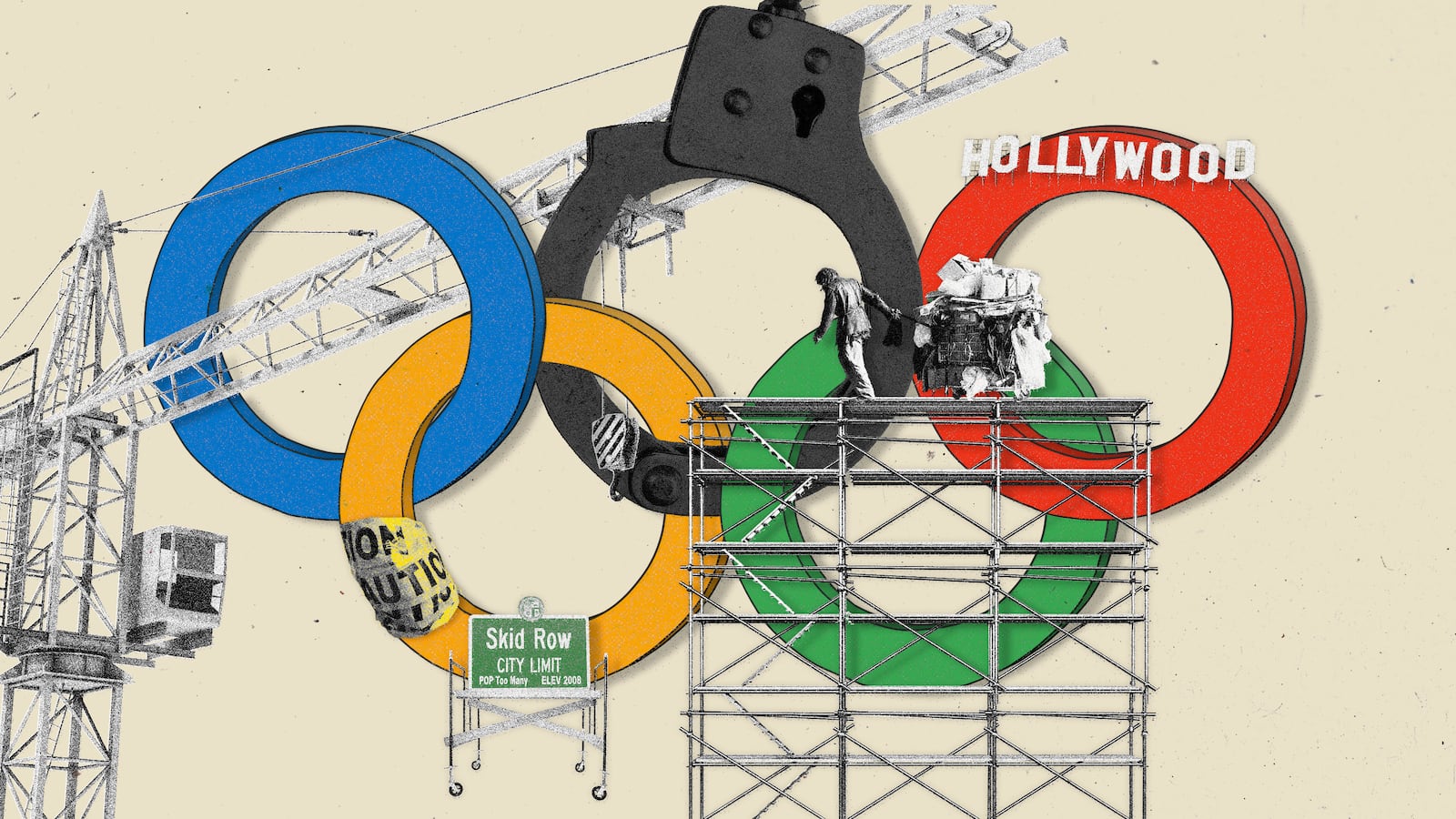

The Kissinger article came at a moment of heightened Olympic-related tension in Los Angeles. The 2028 Games were awarded to the city two years ago in a controversial and unprecedented move–one which will stretch preparation out over the next decade. For an organization called NOlympics, born out of the L.A. chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, that distant arrival poses a major risk for the city—a place already struggling with a homelessness crisis, rabid gentrification, and one of the most notorious police forces in the country. The Games, they claim, will displace marginal populations, further militarize law enforcement, and redirect city resources towards the interests of a wealthy few. The president of L.A.’s Olympic Organizing Committee, for example, is sports executive Casey Wasserman, grandson of mega-Hollywood agent Lew Wasserman, whose Beverly Hills estate was the county’s most expensive house last year, and who logged a flight on Jeffrey Epstein’s private jet.

From NOlympics’ view, the Games not only fail to “realize a more peaceful vision of the future,” but actively sow division, widening the gap between the working poor and monied elite. For the past two years, the group has mounted a campaign with a simple mission: kick the Olympics out of Los Angeles. Recently, as that effort has gained traction with a growing coalition of Angelenos, the goal has become more ambitious: to disprove the myth of the Olympic truce, raise awareness about the Games' proven material consequences, and foster a global movement to end the mega-event for good. Their slogan: No Olympics Anywhere.

By most metrics, L.A. was an unlikely contender for the 2028 Games. In early 2015, after a committee helmed by Wasserman announced a bid—then for the 2024 Olympics—the city lost out to Boston. But a small coalition of Boston activists pushed back on the city’s selection, filing FOIA requests, soliciting polls, and mounting a campaign to pull out of the project. By July, Boston dropped out, kickstarting the search for a new host. In round two, L.A. competed against four other cities—Paris, Hamburg, Rome, and Budapest—but three withdrew, leaving the Cities of Angels and Lights to duke it out. In September of 2017, with global interest in hosting the Games on the decline, the IOC announced an unusual move: a tie, awarding 2024 to Paris and 2028 to L.A.

At the time of the announcement, NOlympics had been underway for several months. Jonny Coleman, an L.A.-based journalist (or “content serf,” as he puts it) and early organizer, dates the first meeting back to April of that year. Coleman has salty brown hair, clear glasses, and, like many of his peers, an encyclopedic memory of Olympic wrongdoing. The writer joined the Democratic Socialists of America in the wake of the 2016 election, alongside scores of millennials disillusioned with the liberal establishment and their failure to address spiking inequality. Coleman joined the chapter’s Housing and Homelessness committee, and as L.A.’s Olympic bid grew increasingly realistic, Coleman said, the group decided to get involved. They wanted to combat the city’s myriad social justice issues, building off the work of L.A.’s vibrant activist community, without stepping on anyone’s toes. There were already many established groups—Black Lives Matter, L.A. Poverty Department, and the L.A. Community Action Network, to name just three—working on problems from housing to gentrification to policing. The Olympics presented a new and complex challenge, operating at the nexus of all three.

The city had ambitious plans for the Games. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who made LA2028 a centerpiece of his tenure, has boasted of hosting the most lucrative Olympics in history, predicting a whopping $1 billion surplus. The profit margin would be an extreme outlier for the mega-event, which has gone over budget almost every year since 1968, according to a 2016 study from Oxford University. Even for the last Los Angeles Games in 1984, which often ranks among the most lucrative in history, profits peaked at $223 million.

To Garcetti’s credit, L.A.’s Olympics proposal was unlike almost any other. Having hosted the Games in 1932 and 1984, the city claimed they could realize a “No Build Olympics” by repurposing existing structures. The event would come at minimal public expense, the bid committee argued, announcing an initial budget of $5.3 billion—a dramatic drop from the average cost of $8.9 billion, according to the Oxford study. (L.A.’s estimate has increased three times since. It’s now $6.9 billion). “Using our existing world class venues, LA 2028 does not need to build any new stadiums or housing,” city spokesperson Alex Comisar wrote in an email, “and will be low-risk, privately funded and fiscally responsible just like the 1984 Games.” The Olympics would serve a public good, he added, generating revenue to fund youth sports programming around the city. “I think we can guarantee universal access to sports,” Garcetti told the Los Angeles Times this year, “possibly forever.”

The NOlympics crowd are wary of those proposed benefits. After the 1984 Games, most of the oft-cited surplus was sent back to the International Olympic Committee, and the remaining $93 million was placed in the care of the LA84 Foundation, a “grant making and educational” non-profit which funds youth sports for underserved populations across Southern California. But NOlympics argues the funds have not been sufficiently reinvested in the city. While tax returns from 2017 put LA84’s assets at over $165 million, their annual contributions hover around $2 to 3 million (the largest expense that year—$345,000—went to a Youth Sports Summit targeted at adults, where tickets cost $395 each).

In an examination of LA84’s returns with former IRS investigator Martin Sheil, The Daily Beast found that LA84 repeatedly donated less than their required annual threshold. Typically, yearly contributions for nonprofits must be equal to their returns on investment. In 2017, tax forms indicate LA84 fell more than $2.6 million short of its required donations; and in 2016, they should have spent an additional $6.1 million. Meanwhile, the foundation had nearly $22 million invested in companies like Blackstone, a controversial private equity firm recently “blasted” by the U.N. for their role in exacerbating the American housing crisis—the very issue NOlympics wants to combat.

The nonprofit has a five-year period to remedy each discrepancy of this kind, though the gaps raise questions about why a nonprofit so well-endowed would face this problem at all. (LA84 did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

But the crux of NOlympic’s concerns lie not with the potential revenue gained by hosting the Games so much as what might happen in pursuit of it. Los Angeles is in the midst of a homelessness epidemic—a crisis so drastic local officials recently called on Gov. Newsom to declare a state of emergency. The 2019 homeless count found that nearly 60,000 people in the county are unhoused and more than half of them live in L.A. proper—a 12 percent and 16 percent increase from last year, respectively. As NOlympics organizers point out, the Games have adverse effects on the groups most vulnerable to homelessness. A 2007 study from the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions found that host cities saw rent spikes, forced evictions, reductions in affordable housing, and widespread gentrification as a direct result of the Games.

For their part, the LA28 organizing committee argues displacement won’t be an issue because the city won’t be constructing anything. But even without the need to build stadiums, NOlympics organizers claim the Games will shift development priorities away from affordable housing to hotels and tourist accommodations. That prediction has already come true. A 2019 report from real estate developer Atlas Hospitality Group found that L.A. opened more hotel rooms last year than anywhere else in the state, and estimated that more than 10,000 would open in the next few years. One contributor to that statistic is The Fig—a new complex equipped with 300 hotel rooms, 200 units of student housing, and 200 apartments, which the L.A. city commission approved in February. The problem: dozens of families already live there in rent-stabilized units—a rare find in Los Angeles’ strangled housing market, and one that won’t be replicated in the new buildings. According to the L.A. Times, the city council hired consultants to determine how much public assistance they could provide the project, “citing the need for hotel rooms to accommodate tourism and the future Olympic and Paralympic Games.”

That displacement goes hand in hand with another key concern: the overextension of law enforcement. The same 2007 report wrote that staging the Olympics “also involves ‘clearing’ homeless persons off the streets, often by forcing them to move to other cities or areas, or jailing them.” The 1984 Games, on which the 2028 Olympics are modeled, brought about an unprecedented wave of mass arrests—of unhoused people, but primarily of black and Hispanic youth, in what would later be dubbed the “Olympic Gang Sweeps.” In the five years following the Games, according to The Nation, there was a 33 percent increase in citizen complaints of police brutality. Part of NOlympics’ platform stems from a fear that the future Games will bring similar conditions, in the name of “cleaning up the streets” for two weeks in the international spotlight. It’s a fair concern—even the current President of the Los Angeles Police Commission Steve Soboroff agrees. In an email exchange FOIA’d by NOlympics, Soboroff sent a Curbed article about the mistreatment of the homeless during the 1984 Games to Wasserman. “It’s a different LAPD than 1984,” he wrote, “but the questions are valid.”

In early September, Coleman and a dozen other NOlympics organizers filled the front rows at a meeting of L.A. City Council’s homelessness and poverty committee. They weren’t the only organizers there. The meeting hall was packed with activists from various groups—all from Services Not Sweeps, a coalition of community organizations dedicated to bringing unhoused people aid, rather than raids (or “sweeps”) from law enforcement. They had come to protest a proposed ordinance called 41.18.(d), which would make it a criminal offense to sit, lie, or sleep within 500 feet of schools, parks, day-care centers, and a wide range of other public facilities.

When the public comment section arrived, a writer and NOlympics organizer named Molly Lambert got up to read a statement. It came from a woman named Tessa, a Los Feliz resident and mother of two.

“My children are old enough to ask about the camps they see and they are old enough to be told the truth,” Lambert read. “Inside these tents are people with medication, including life saving medication which is regularly confiscated by the police. Inside some of these tents are people who can’t afford to rent some of the most modest apartments in our unaffordable city. Inside some of these tents are children, including children who share classrooms with my children and yours. When we tell unhoused people that they are breaking the law by existing in spaces adjacent to schools and parks, we are not helping our kids. We are lying to them. We are telling our kids that only some people should have access to human rights—that being poor is a crime. We’re telling them to turn away from people who suffer—to resent seeing them at all.”

Lambert choked up as she finished. She wasn’t the only one. The meeting hall erupted in hoots, cheers, and applause. The three council members who had shown up seemed bored. One picked at the label of his water bottle. An audience member yelled: “Pay attention!”

Several city officials who spoke to The Daily Beast for this article expressed confusion at NOlympics’ campaign—at their frequent appearances in city meetings that have no obvious association with the Games. A representative for the mayor’s office, who spoke to the Daily Beast on background, claimed the group had misrepresented their intentions. “The D.S.A.’s arguments have changed over time. The city isn’t building anything—there are none of the normal expenses that you see with Olympics stadiums,” he said. “They’re constantly evolving their complaints. It’s disingenuous. This has nothing to do with the Olympics. This is about a problem with the city and the mayor.”

But for critics of the Games, those things are inseparable. Supporters see the Olympics as a truce—a cartoon pause button, where existing tensions and problems are put on hold for an international celebration of human achievement, like some global Hands Across America with billions of dollars at stake. But the Olympics aren’t merely a celebration of otherworldly athleticism—they’re a massive undertaking that has a proven impact on local priorities and in determining who benefits from public resources and who is punished by them.

Representatives for the Olympic Organizing Committee and the Mayor’s Office told The Daily Beast that even if they wanted to end the Games, they couldn’t. They signed the contract. The deal is done. But there is precedent for a movement of this nature. In 1972, after Denver agreed to host the 1976 Winter Games, the city rescinded their bid. The move came after a city-wide referendum, pushed onto the ballot by activists in both parties—fiscal conservatives wary of using public funds, and progressive lefties concerned for the environment. If NOlympics can rally something similar, they may be poised to recreate that model.

“This is happening at a time when there’s widespread skepticism about the benefits of the Olympics,” said Jules Boycoff, Olympics scholar and author of the upcoming book Activism and the Olympics: Dissent at the Games in Vancouver and London. The group has already found supporters across the globe–on Nov. 18, NOlympics will host an to discuss the Games' impact on working people, with presentations from far-flung advocates like Tokyo's anti-Olympics group, Hangorin No Kai. “They should rally their resources to get a referendum," Boycoff continued. "It’s complicated in California, but that’s the best way to kick the Games out for good.”

An earlier version of this article identified Steve Soboroff as the Los Angeles Chief of Police. He is the President of the Police Commission.