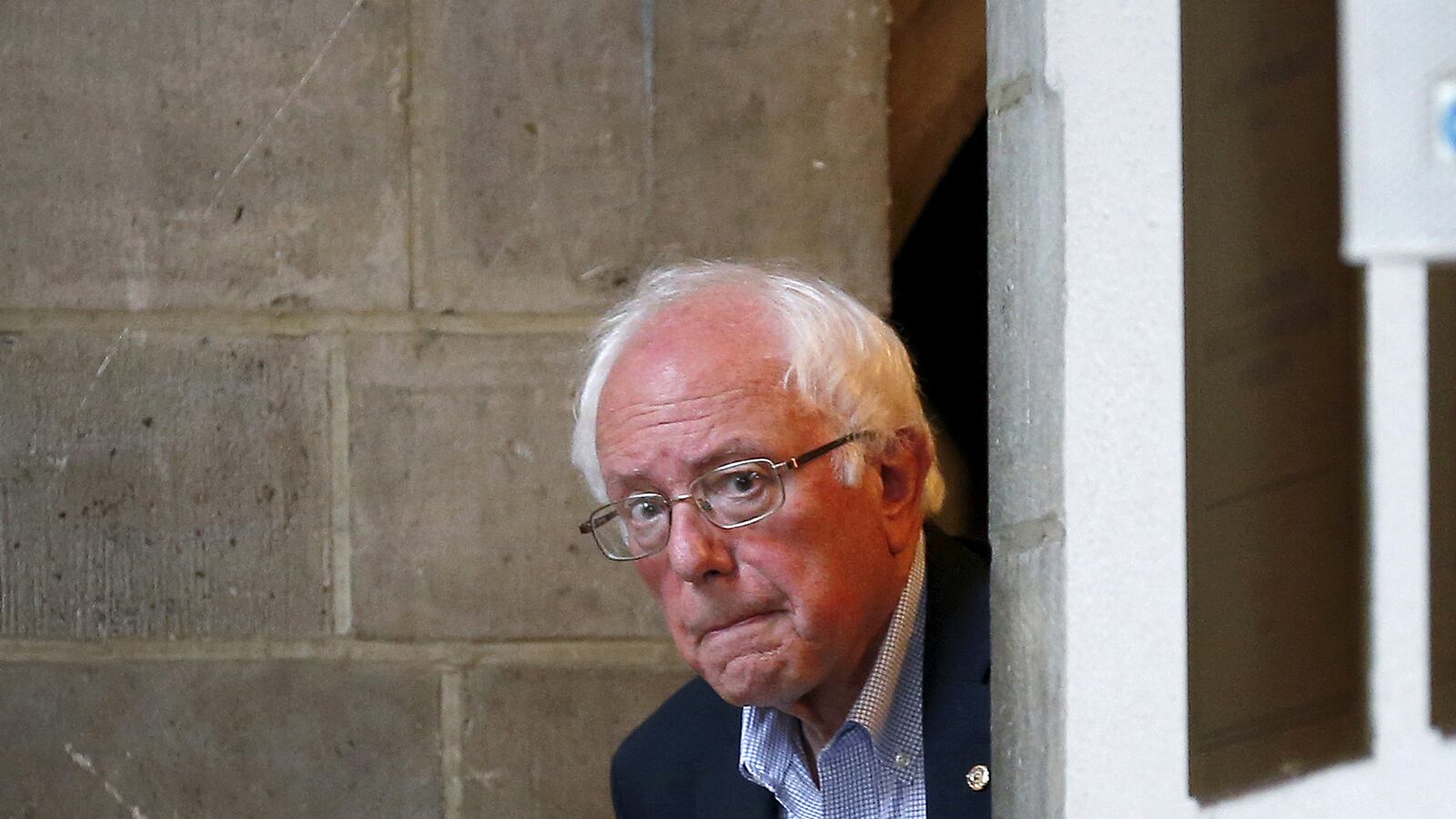

When Sen. Bernie Sanders regales his campaign crowds with a portrait of The Way Things Are Going to Be, his “Medicare for All” program takes center stage. In a Sanders administration, the candidate promises, every man, woman, and child in America will share in a government-run, government-funded health-care system.

But the single-payer system that Sanders is evangelizing isn’t just a figment of progressive utopian fantasies. Single-payer health care has already been tried—and failed—in Sanders’s home state of Vermont, where the proposal collapsed under its own weight last year before it was ever implemented.

Deciding why it failed in Vermont is key to whether you buy into the candidate’s promise to extend the program nationwide.

According to critics, from The New York Times’ Paul Krugman to USA Today’s editorial board, Sanders’s single-payer plan is something between a well-intentioned fool’s errand and a political pipe dream, an unrealistic idea that has been proven not to work in the senator’s own backyard.

But closer to home, activists say Vermont’s failure even to implement its plan for universal health care was a failing of political will, not the policy itself. In better hands, they say, the policy can still work. To know the difference, it’s important to understand how Vermont got so close to single-payer in the first place.

In 2011, the state’s Democrat-controlled legislature approved a government-run, government-financed health-care system for all Vermonters. The state’s new Democratic governor, Peter Shumlin, signed the bill into law after campaigning on a pledge to enact single-payer himself. A cost estimate of the program, known as Green Mountain Care, was ordered, but long delayed.

Elections came and went, including Shumlin’s own 2014 reelection, which was so close Vermont law required the final decision to go to the legislature after Shumlin failed to win a majority of the vote in November. As the state waited for the legislature to take up the election results, Shumlin announced that he would not pursue single payer after all when the long-awaited financial projections showed “the promise and the peril” of a single-payer system. The promise, of course, was a chance to give nearly every Vermonter reliable access to quality health care.

But the very real peril came in the cost for the program, an estimated $4.3 billion a year, almost the size of the state’s entire $4.9 billion budget. To make up for the $2 billion shortfall, taxes would have to go up, a lot. Businesses would see an 11.5 percent payroll tax increase, on top of whatever they chose to provide for employee health care, while individual income taxes could jump by up to 9 percent. The report recommended against moving forward “due to the economic shock and transition issues,” and Shumlin agreed.

“I wanted to fix this at the state level. And I thought we could,” Shumlin said in a statement issued with the financial report. But he called implementing single-payer health care in 2015 “unwise and untenable.”

Despite the ominous budget projections at the time, single-payer advocates now say they believe Shumlin’s decision was purely political.

“Right up to the last gubernatorial election, Gov. Shumlin was saying he was going to do everything he could to make single-payer health care a reality in the state. That was quite frankly why we didn’t run a candidate against him,” said Kelly Mangan, the executive director of the Vermont Progressive Party. “Almost immediately, he turned around and said, ‘Oh, yeah, we can’t afford single-payer health care. It’s not going to happen.”

Mangan described single-payer advocates today as “fatigued and very disheartened.” As Vermont’s state budget continues to be squeezed by Medicaid costs, she said the possibility of returning to the issue any time soon seems unlikely. She also worries that Vermont’s example will damage future prospects nationally. “I think it will have a ripple effect. People will use it as an excuse to do nothing by saying, ‘If they couldn’t do it there, then it can’t be done,’” she said.

Dr. Gerald Friedman, an economics professor at UMass-Amherst and a part-time Vermonter, has worked with Sanders to develop and calculate the cost of his plan and says the budget wasn’t the problem for the Vermont proposal. The governor was the problem.

“On the economics, it would have been cheaper, but the governor just lost the political will,” Friedman said.

But the professor acknowledged that any national health care proposal from Sanders would face the same political headwinds that Shumlin ran into. “It’s going to be a tough road, and Vermont is a lesson,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that it happened the way it did.”

Even with the Vermont debacle in the rearview mirror and Friedman’s own projections that Sanders’s “Medicare for All” would cost north of $14 trillion over 10 years, the politics of single-payer are still working for Sanders. The latest Kaiser poll showed 81 percent of Democrats favor a “Medicare for All” proposal, while 60 percent of independents favor it, too.

Clinton has dismissed Sanders’s proposal as unrealistic and a danger to the reforms that have already been enacted through the Affordable Care Act. That argument seems to be falling flat in New Hampshire, where the latest WMUR poll showed Sanders trouncing Clinton by nearly 30 points. But at least Clinton can count on some support when the campaign gets to Vermont. Gov. Shumlin, who will not run for reelection, has announced he’s with her.