In 2013, nine “privileged twentysomethings” faced the reality-TV switcheroo of the century when they arrived for the Canadian reality show The Project: Guatemala. They thought they were headed to a luxury retreat in Guatemala, but instead they’d been enlisted to build a community hall for orphaned children. Along the way, they’d also face tasks that would test them “physically, mentally and emotionally.” For one “challenge,” producers convinced the cast that they were about to die in a plane crash.

When they heard there was a “problem with the engine,” the young passengers screamed, cried, and prayed. As soon as the plane landed some could be seen sobbing, hugging one another, and kissing the ground. One young woman said through tears that she wanted to go home. Host Ray Zahab later revealed that it was all just a ruse.

“That’s not even the worst thing I've heard,” Love Is Blind alum Jeremy Hartwell told The Daily Beast during a recent phone interview. Having spoken with reality stars from across the decades (and around the globe) along with his Season 2 castmate Nick Thompson, he’s heard far too many anecdotes of deception, betrayal, and exploitation.

Some viewers might insist that “fame-hungry” reality stars know what they are signing up for, but some veterans of the genre argue the opposite. Earlier this year, Hartwell and Thompson founded the UCAN Foundation—which aims to provide legal and mental health support to cast members, advocate for change in the industry, and educate the public about the working conditions on these shows. In doing so, they’ve joined a growing number of former reality figures who’ve used their platforms to speak out about their experiences.

The cast of season two of Love is Blind

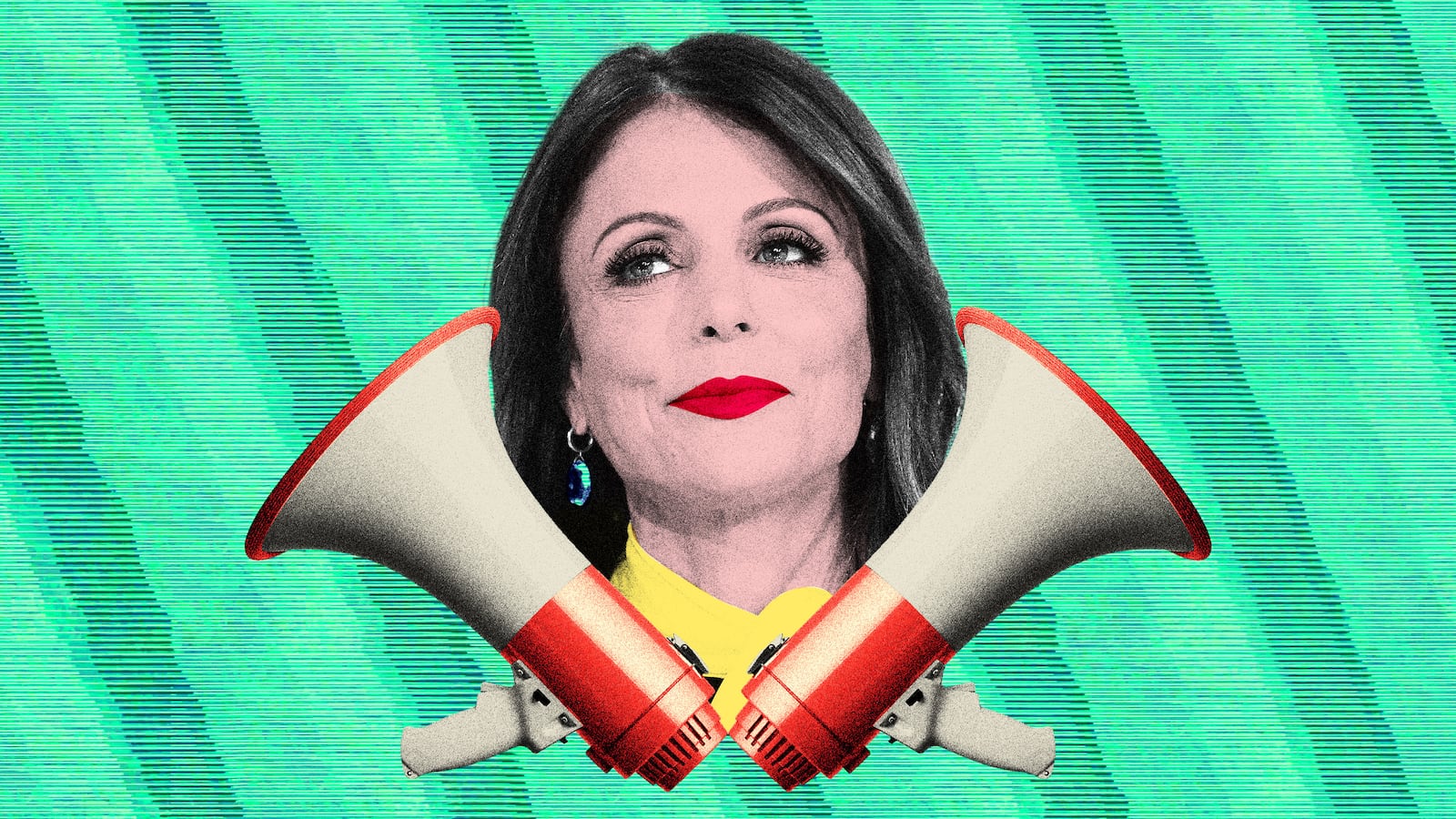

Netflix/Ser Baffo/NetflixNow, as Hollywood’s dual strikes press on and Real Housewives of New York star Bethenny Frankel pushes for a reality performers union, it seems our hot labor summer is coming for reality TV.

“To use the union slang,” WGA East executive director Lowell Peterson told The Daily Beast, “there’s more heat than ever.”

Defense attorney Mark Geragos, who is representing Frankel alongside attorney Bryan Freedman as she calls for a “reality reckoning,” told The Daily Beast that they’ve heard from hundreds of reality stars who are interested in their effort. “It may even be close to 1,000,” he said.

In August, Geragos and Freedman sent NBCUniversal (which owns Bravo, home of the Housewives, Vanderpump Rules, and Below Deck) a litigation hold letter that accused the company of “grotesque and depraved mistreatment” and covering up “acts of sexual violence.” (A representative for NBCUniversal did not respond to The Daily Beast’s request for comment.)

In their letter, Freedman and Geragos demanded that the conglomerate preserve all documents including those related to its policies “regarding sexual violence and harassment in connection with cast members and/or crewmembers on its reality TV Shows,” as well as those concerning the company’s “exploitation of underage participants” on those programs. They accused NBC of “Distributing and/or condoning the distribution of nonconsensual pornography,” and ordered the company to save all “audio and video of sexual activity involving cast members on NBC’s reality shows” still in its possession—“whether taken by cast members, crewmembers, or third-parties.” They also ordered that the company preserve all communications “from or to NBCUniversal employees and/or contractors, including but not limited to executives, concerning the suicide or attempted suicide of castmembers and/or crewmembers on NBC’s reality shows.”

Speaking with The Daily Beast, international feminist attorney Ann Olivarius compared the boundary manipulation and violations reality participants can face to the ways in which the porn industry can prey on young women as they break into the industry.

“I think we’ll see a lot of lawsuits coming out of these players,” Olivarius said of the reality studios. “We’ve actually been approached by a number of these women who have said, ‘No, what happened to me there was not the deal. It was not what I signed up for. I wasn’t told about this.’"

As Olivarius pointed out, a union would standardize and enforce reasonable workplace terms and conditions including wages and overtime. It could also provide a powerful venue to file complaints if and when things go awry. In other words, “a union could be God's gift for this whole profession.”

For some, however, the damage is already done. Looking back on his less-than-positive Love Is Blind experience, Thompson wondered aloud whether he’d ever feel “how I did before again.”

“It just impacts your life in ways that you could never even imagine.”

Reality television exploded in the 1990s and early 2000s, but the genre had really got a boost in the late ’80s. Amid the 1988 writers strike, studios developed shows like Cops, America’s Most Wanted, and Unsolved Mysteries to fill the hole left behind by scripted series. Then, in the 1990s, reality flourished even further as studios embraced conglomeration and sought out formats they could reproduce internationally—like Big Brother. By the 2000s, seemingly everyone wanted in on the reality game.

During strikes, studios can sometimes use reality television as a cudgel—a reminder to unionized writers that their work is replaceable. According to WGA executive director Peterson, however, that tactic didn’t pan out during the last strike—which has only emboldened writers this time around.

If anything, Peterson said, studios’ insistence on treating all content as interchangeable only bolsters the guild’s argument to organize the writer-producers who help create so-called “reality” television by writing questions, creating “characters,” and stringing together or even creating narrative.

“If studios say, ‘Hey, it’s all content, we don’t care,’ then it sort of undermines the argument that there’s something unique about reality TV,” Peterson said. In the long term, he predicts, the unscripted world will begin to look more and more like its scripted counterpart—at least from a labor perspective.

Even the term “reality television” seems to obscure the production work that goes into it. As Peterson put it, “I think it’s a bit of a marketing smokescreen.” The WGA East’s reality writers workshop includes training for skills like character creation and story arcs generation.

Then again, there’s something poetic about that little deception; bait-and switches are, after all, the genre’s bread and butter.

Gary King in Below Deck: Sailing Yacht

BravoMillennials of a certain age will likely never forget 2003’s Joe Millionaire, in which a group of women competed for a man they believed to be a millionaire who was actually an “average Joe.” These days, we have The Ultimatum—which, at least during its first season, apparently did not tell some of its contestants they’d be giving an ultimatum or partner swapping at all. Lifetime’s scripted hit UnReal unmasked the manipulation that goes into The Bachelor, and earlier this year, TLC unveiled its unholy dating show MILF Manor—which appeared to surprise its participating mother-and-son duos with the news they’d be dating across decades-wide age gaps.

According to Hartwell and Thompson, the manipulation starts before the cameras start rolling. Hartwell recalled that a former casting director once told him that casting departments come up with character archetypes to deliberately seek out. “She said from the very first contact they have with you, they are manipulating you,” he said. “Slowly moving you along a set path in a certain way, gaslighting you, making promises they know they can’t keep, pretending to be your friend even though they know it’s going to be betrayed later.”

Thompson recalled talking to his producer for 10 to 12 hours through a series of digital meet-ups and virtual happy hours before Love Is Blind Season 2 began. Producers will present themselves as participants’ friends, he said, and assure them that their program is “different from other shows.”

As for the whole “they knew what they were signing up for” thing, reality television contracts can be vague—and as Hartwell and Thompson point out, those signing them tend to expect that they’ll still be treated like human beings. “You think to yourself, ‘Well, I’m just going to be me,’” Thompson said. “‘What could possibly go wrong?’

“Then they edit a scene out of order, or they conduct Franken-biting,” he added, referring to a commonly deployed editing trick in which producers splice together quotations or otherwise manipulate audio to put new statements in contestants’ mouths.

Contestants might know going in that they’ll need to give up their phones, as was the case on Love Is Blind, but as Thompson noted, they might not realize that their wallets, passports, and credit cards will also be confiscated on Day One. They might not expect to be held in a room without a hotel key, or filmed for 18 to 20 hours per day.

“All of this stuff is just not presented in any meaningful or, or comprehensive way that the average person can understand,” Thompson said. The show’s contract also includes a $50,000 penalty for leaving early—guaranteeing that the vast majority of contestants cannot exit unless granted an exception. Once you’re there and they’ve taken your credit card and passports, the two said, leaving becomes pretty much impossible.

Attorney Olivarius likened the idea that reality stars don’t deserve sympathy because they wanted fame or because they “knew what they were signing up for” to saying that a girl was “asking” to be raped because of what she was wearing at the time.

“What they share, all of these shows, is that people in the business look at them as if they’re the loser… they’re not the ‘talent,’” Olivarius said. In many cases, she added, contestants on these shows are seen as having a lot to gain from their exposure on TV—which can strengthen the resistance against them when they do speak out.

Both Olivarius and Geragos noted that many of the liability waivers and non-disclosure agreements studios ask participants to sign are legally unenforceable, especially after California tightened its restrictions on NDAs. That said, most of these shows’ participants lack the funds and clout required to actually challenge these pacts.

Enter, Bethenny Frankel—a mega-wealthy entrepreneur and leading member of reality television’s rarefied celebrity class who also now happens to be clamoring for a reality union, with help from two high-powered attorneys.

The WGA has seen an uptick in organizing interest from reality workers during the strikes, Peterson said, and beyond that, the reality-check statements from Frankel and other high-profile genre stars seem to indicate “that people are sort of fed up.”

“You wouldn’t ever have thought of reality stars going public with their gripes 10 years ago, would you?” Peterson asked. “I don’t think so.”

Bethenny Frankel in Real Housewives of New York

BravoAt this point, Geragos said, he and Freedman have heard from former cast members from across the spectrum of reality television—not just at NBC, but at “almost every single network and production company.” NDAs have become a key battleground, as Freedman and Geragos have alleged that “unlawful” NDAs have silenced “hundreds or thousands” of people and helped “hide civil and criminal wrongs.” A representative for Bravo, meanwhile, told The Wrap that these agreements “are not intended to prevent disclosure by cast and crew of unlawful acts in the workplace, and they have not been enforced in that manner.”

Geragos described the team’s tactic as a “three-pronged war”: Beyond advising NBCUniversal to retain certain records in case of any potential litigation, the attorneys have also partnered with SAG-AFTRA on the labor organizing front and plan to focus on legislation next.

Buzz aside, however, as Hartwell and Thompson pointed out, there are some very real, practical obstacles standing in the way of this effort. For one thing, most reality stars are contract workers—which means that their organizing will likely look a little different, since contract workers cannot legally unionize in the same way full-time employees can. That said, Hartwell also alleged in his 2022 lawsuit against Netflix, Love Is Blind producer Kinetic Content, and Kinetic’s casting company Delirium TV that the streamer “willfully misclassified” contestants as independent contractors. He and Thompson allege that they both received W-2 forms.

In a statement to Variety last summer, Kinetic Content noted that Hartwell participated in the season for “less than one week,” adding that there “is absolutely no merit to Mr. Hartwell’s allegations, and we will vigorously defend against his claims.” Representatives for Netflix and Kinetic did not respond to The Daily Beast’s request for comment.

More than any scandalous anecdote, a source told The Daily Beast that labor misclassification could ultimately pose the real existential threat to studios’ current reality methods—especially given the hefty penalties California can impose for such infractions.

Looking back on his 15 years of experience working to organize reality television writer-producers, Peterson noted that different factions have used different methods—sometimes, even within the same guild. While the WGA East works to unionize production studios, many of which produce multiple reality shows at once, its counterpart on the West Coast organizes individual productions. The guild’s two biggest obstacles? Employer opposition (in other words: union busting), and making sure that people both within and outside the guild remain invested in the fight.

“At the end of the day, there isn’t a magic bullet,” Peterson said. “There’s only solidarity and leverage.”

Ultimately, Peterson said, the goal is to organize enough reality studios and shows to begin setting industry-wide standards. “It’s not as painstaking and slow as it sounds, but it’s still brick-by-brick and not building-by-building,” he said.

The public’s growing awareness about the working conditions on these shows can be a useful source of pressure—and an army of angry Housewives could help with that. The key, Peterson said, is to determine which discussions might compel studios to settle, for fear of duking them out in public.

Still, Peterson added, “To be successful, it’s got to be run as a real organizing campaign, where you have the support of the people actually doing the work and you make sure that they’re committed and willing to take risks.”

Thompson stated it even more plainly: “If we’re going to actually organize, it’s not about one person—it’s about all of us.”