As part of his Don Quixote-like quest to avoid criticism, Attorney General Merrick Garland has binged on special counsel appointments throughout his tenure at the U.S. Department of Justice.

Now, following a string of debacles, including allowing Special Counsel John Durham to continue his useless four-year probe of the Mueller investigation—elevating the Hunter Biden prosecutor, David Weiss, to special counsel status after a half-decade of investigation—Garland’s hand-picked Special Counsel Robert Hur has produced a report on President Joe Biden’s handling of classified information that rivals former FBI Director James Comey’s infamous political hatchet-job on Hillary Clinton’s campaign.

Hur concludes what everybody already knew—namely that no criminal charges are warranted in Biden’s handling of classified materials—but gratuitously slams Biden’s fitness for office by describing him as a “sympathetic, well-meaning elderly man with a poor memory.” By allowing this unprofessional, partisan dig to be published, Garland plays right into the hands of former President Donald Trump and the extreme right’s ageist attacks on the president.

To be fair, maybe Hur was only trying to exercise what he thought was proper prosecutorial discretion in not bringing a weak case. Or perhaps, he may just be an inept, clumsy writer/editor.

But it was Garland’s responsibility to ensure that Hur’s report did not stray from proper Justice Department standards. Garland should have known the risks when he picked Hur—who had clerked for conservative Chief Justice William Rehnquist, served as the top aide to Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who assisted Bill Barr’s distortion of the Mueller Report, and who was a Trump-appointed U.S. Attorney.

The bottom line is that Hur has produced a report that should have reassured the American people that President Biden did nothing wrong, but instead supplies Biden’s political rivals with ammunition for baseless attacks on Biden’s fitness for office.

Hur opens his report in a way that invites misinterpretation, by stating he “uncovered evidence that President Biden willfully retained and disclosed classified materials.” But Hur waits until the next paragraph to state that the evidence does not establish Biden’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

United States Attorney Robert Hur speaks at a news conference on Sept. 19, 2018 in Baltimore, MD.

Zach Gibson / Getty

The verb “uncovered” suggests evidence was hidden and only Hur’s skillful investigation discovered it. Nothing could be further from the truth, as the rest of the report demonstrates that President Biden hid nothing from the investigation and was entirely forthcoming. Hur’s wording also makes it sound like he believes Biden committed a crime, but he just can’t prove it when his report actually concludes there is a lack of evidence of Biden possessing criminal intent to commit a crime.

A report explaining the reasons for declination should be written in a very factual, non-pejorative way. Hur should have simply said that the evidence found in the investigation did not support a recommendation of criminal prosecution, and then gone on to explain what evidence had been evaluated.

Again, maybe Hur’s just a lousy writer. But an examination of his analysis belies that benign interpretation.

Hur justifies his put-down of Biden’s mental acuity and memory by invoking the Department of Justice’s Principles of Federal Prosecution, but those regulations do not support Hur giving his “I’m not a doctor but play one on TV” opinion about Biden’s mental acuity. Hur is suggesting that the “sympathetic” nature of Biden’s supposed age-related infirmities will make jurors unlikely to convict him.

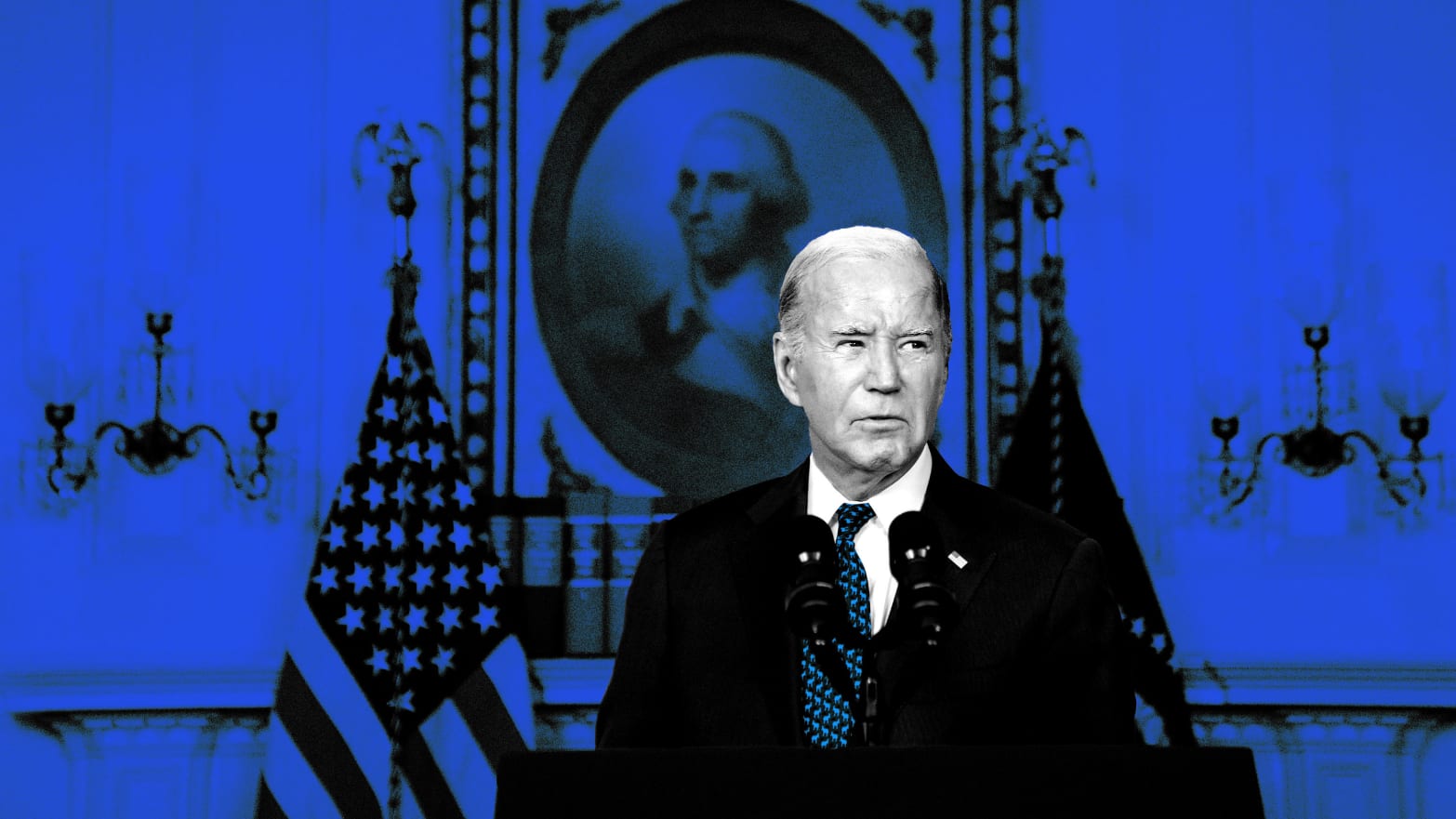

President Joe Biden delivers remarks in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House on Feb. 8, 2024.

Nathan Howard / Getty

But the DOJ regulations cited by Hur actually cut against this as a reason for declining prosecution:

“Where the law and the facts create a sound, prosecutable case, the likelihood of an acquittal due to unpopularity of some aspect of the prosecution or because of the overwhelming popularity of the defendant or his/her cause is not a factor prohibiting prosecution. For example, in a civil rights case or a case involving an extremely popular political figure, it might be clear that the evidence of guilt—viewed objectively by an unbiased factfinder—would be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction, yet the prosecutor might reasonably doubt, based on the circumstances, that the jury would convict. In such a case, despite his/her negative assessment of the likelihood of a guilty verdict (based on factors extraneous to an objective view of the law and the facts), the prosecutor may properly conclude that it is necessary and appropriate to commence or recommend prosecution and allow the criminal process to operate in accordance with the principles set forth here.”

In other words, a prosecutor should not decline to prosecute just because he is worried about losing due to the defendant looking sympathetic to the jury.

Of course, prosecutors have to take into account how a defendant will come across to a jury, but while a sympathetic defendant may make a case hard to win, that is not a reason to decline prosecution at the outset.

Hur also asserts on page 249 of his report that by the time of trial or sentencing Biden “would be well into his eighties, an age when relatively few people are prosecuted” and again cites DOJ regulations. But those regulations do not give any statistics about how many people are prosecuted at that age, nor does Hur offer any such statistics. In the comments to the regulations, “advanced age” is referenced as a factor that can be considered part of “personal circumstances,” but there is no specific age range given.

President Joe Biden answers questions about Israel after speaking about the Special Counsel report in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House in Washington, DC, on Feb. 8, 2024.

Mandel Ngan / Getty

In fact, as pointed out by one legal commentator, the observations about Biden’s ability to recall various facts today are irrelevant to his actions at the time being investigated, and Hur should have followed the basic DOJ protocol of “put up or shut up.”

The amount of writing that Hur devotes to comparing Biden’s actions to Trump’s is also questionable. On the surface, Hur appears to be legitimately explaining that the past cases do not justify charging Biden.

For example, Hur notes on page 10:

“Historically, after leaving office, many former presidents and vice presidents have knowingly taken home sensitive materials related to national security from their administrations without being charged with crimes. This historical record is an important context for judging whether and why to charge a former vice president and former president, as Mr. Biden would be when subject to prosecution—for similar actions taken by several of his predecessors.

“With one exception, there is no record of the Department of Justice prosecuting a former president or vice president for mishandling classified documents from his own administration. The exception is President Trump.”

Hur goes on to explain aggravating factors in Trump’s actions that potentially justify why Trump is being charged. But this is improper to do because Hur is commenting on a different, pending prosecution of a different person in a case over which he possesses no authority. The nefarious aspect of this comparison is it gives a roadmap for Trump to argue why Hur’s comparison is wrong. It would have been enough for Hur simply to say that the weight of historical precedent cuts against Biden in the absence of aggravating factors like being given multiple chances to return documents and obstructing justice. But by specifically invoking the Trump case, Hur invites comparison.

Attorney General Merrick Garland’s formative experience at DOJ was during the era of independent counsels, not special counsels. The difference is important because independent counsels operated outside the supervision of DOJ and the attorney general, but special counsels do report to the attorney general.

Perhaps Garland unconsciously defaults to this earlier era of a codified “hands-off” approach, but that is the wrong approach. Garland had a duty to oversee this investigation and the report produced. He failed, and the consequences of that failure—like his delay in appointing Special Counsel Jack Smith—loom large over the future of our country.