The new documentary Billion Dollar Heist ends with a jolting premonition: In the next five to 10 years, a cyberattack threatening major national infrastructures—banking, transportation, telecommunications, water supplies—is all but guaranteed.

The warning comes from Misha Glenny, a London-born cybersecurity expert and the author of the 2008 book McMafia: A Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld (later adapted into a TV series starring David Strathairn and James Norton). Glenny appears in the film to help explain the story, through which a cabal of hackers committed the most ambitious digital heist in history, stealing $81 million from Bangladesh’s central bank. If someone could get away with a crime of that magnitude in 2016, there’s worse around the corner, Glenny argues, especially as artificial intelligence becomes more sophisticated.

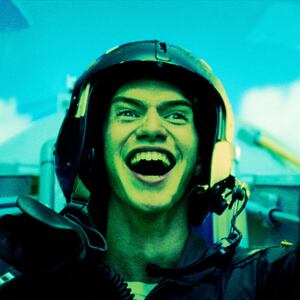

British journalist and broadcaster Misha Glenny.

David Levenson/Getty“It’s a permanent black-swan situation,” Glenn tells The Daily Beast, referring to a common theory of probability. “You have a low risk of something bad happening, but if something bad does happen, then every year the consequences are going to be even greater because of the scale of our dependency on complex, networked computer systems.”

In less than 90 minutes, Billion Dollar Heist (now available on VOD) details how the Bangladesh bank crime was orchestrated. The hackers spent months slowly infiltrating the South Asian country’s equivalent to the U.S. Federal Reserve, hiding malware in an email sent to 36 of the bank’s employees. Once the programmers gained access to SWIFT, the international system that facilitates transactions from one bank to another, they could launder money via accounts they’d set up in the Philippines. Those funds were then converted to cash by way of Chinese casinos.

The thieves had set their sights on stealing nearly $1 billion, almost all of the bank’s holdings. They were clever about it, too, executing the scheme over four days in February when both Bangladesh and China had banking holidays. An intermediary rejected some of the hackers’ transfer requests, which is why the group only made off with $81 million. But it was still a seismic payday that raised major alarms for cybersecurity specialists like Glenny. An FBI agent featured in the documentary compares the operation to Ocean’s Eleven, where everyone involved has a specific part to pay.

The National Security Agency and the United Kingdom’s Government Communications Headquarters believe the heist was carried out by the Lazarus Group, the same North Korean agency that hacked Sony Pictures in 2014, exploited cryptocurrency operations in South Korea in 2017, and attempted to breach AstraZeneca in 2020 while the pharmaceutical company was conducting COVID-19 vaccine research.

Unlike Russian or Chinese infiltrators, Glenny says, the North Korean perpetrators are more interested in money than espionage. Factions like Lazarus recruit computer whizzes as young as 12 years old, training them to carry out elaborate plots in exchange for cash or luxury goods. Every day, there are thousands of small cyberattacks across the world, according to Billion Dollar Heist, which was directed by Daniel Gordon (30 for 30, The Trials of Oscar Pistorius).

Glenny lists cybercrime as one of the four leading threats to humanity, the other three being climate change, pandemics, and weapons of mass destruction. As former New York Times cybersecurity reporter Nicole Perlroth points out in the film, the internet was originally set up to share resources at the Pentagon, not to absorb the complicated banking and security clearances required today. Now that AI programs like ChatGPT can write disruptive malware, the likelihood of an offensive far greater than the one involving the Bangladesh bank has escalated. After all, most tech companies prioritize innovation over security.

“Artificial intelligence is going to take us on to another level,” Glenny says, “not just in terms of what we can do with network systems, but what can be done to us with network systems.”

He recommends taking a couple of precautions. First and foremost, if your computer or phone prompts you to update its software, do so immediately—it could be a response to a security breach that’s rendered consumer data vulnerable. Secondly, install an antivirus program. Finally, make your passwords as hard to guess as possible.

Of course, individuals aren’t likely to be targeted in the same way that banks and multinational corporations might. Regardless, viruses spread.

“If you use basic digital hygiene, you are reducing your risk level very dramatically—down to about a 3 percent to 4 percent risk, instead of about 16 percent to 20 percent,” Glenny says. “Then, usually, the only way that you’re going to be attacked is if you open an attachment for what is obviously not a not a serious email or you are being targeted. But if you’re being targeted by somebody like the Lazarus Group or that level of hacking, then there’s nothing you can do about it anyhow.”