In the deep forest of stars that lies at the center of galaxies, a voracious monster lives: a black hole millions or billions of times more massive than the Sun. These cosmic beasts are more ambush predators than hunters, though: they only feed on hapless stars and other objects that get too close. Otherwise, they are content to sit quietly if they can’t get any prey for long times.

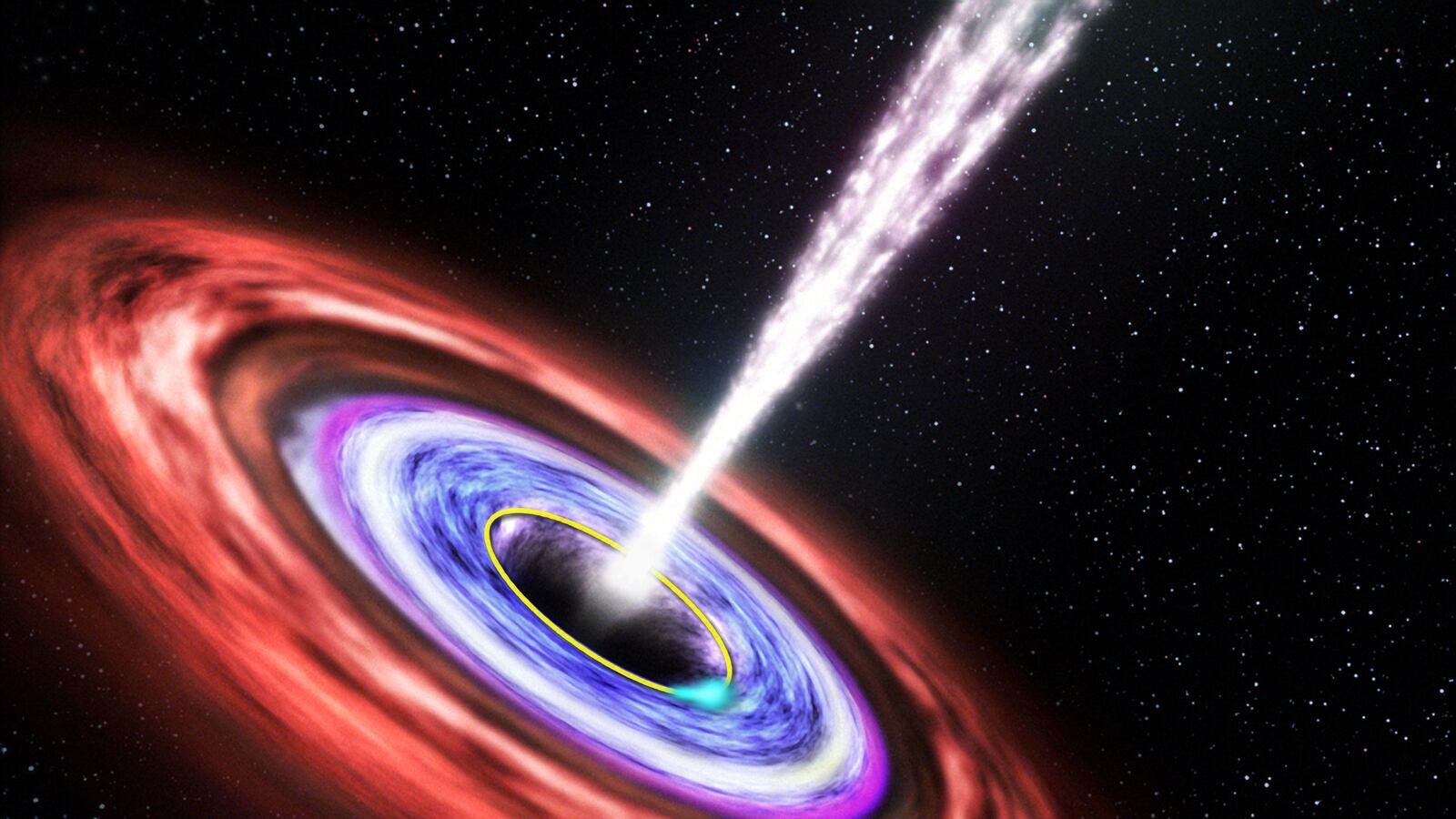

Sometimes a quiet black hole will wake up in a dramatic way, when a star, gas cloud, or even a rogue planet comes within gravitational reach. When that happens, forces similar to those that raise tides on Earth shred the unlucky object, eating some of its mass, and spewing the rest back into space. The stuff that doesn’t fall in can emit a lot of light, turning the black hole—perhaps briefly—into a tiger burning bright in the forest of the night.

Now, astronomers F. K. Liu, Shuo Li, and S. Komossa identified a pair of black holes in the act of cooperatively dismantling a defenseless star. Such pairs of black holes are rare, and a star drifting close enough to get shredded is rarer. Not least, this feeding frenzy could provide insight into the way the biggest black holes in the Universe form.

The size of the central black hole is correlated to the size of its galaxy. (More properly, it’s related to the mass of the central region of the galaxy, but that’s a detail.) Big galaxies tend to have huge black holes, just as a larger forest can support larger predators. One extremely massive black hole we know is nearly 7 billion times the mass of the Sun, and the galaxy hosting it—a huge blob of stars known as M87—is one of the biggest we’ve observed. (For comparison, the Milky Way’s black hole is about 4 million times the Sun’s mass.)

Did supermassive black holes like the one in M87 get that way by eating stars? (Lower-mass black holes, such as Cygnus X-1, are the remnants of very massive stars; those are a story for another day.) The answer is no: despite the stereotype, black holes don’t suck everything in around them. Just like anything else, their gravity is strongest close by, and diminishes approximately with the square of the distance. That means twice as far from the black hole, the gravitational force is roughly four times as weak. The Sun doesn’t feel a significant gravitational pull from the Milky Way’s black hole, which is more than 25,000 light-years away. Most any galaxy’s stars are far out of reach.

So could M87’s black hole have been born that way, like Lady Gaga sang? Supermassive black holes have been around for as long as their galaxies: those are the quasars used by BOSS to measure the acceleration of the Universe, as I described in my earlier column. However, early galaxies and their black holes were smaller than their modern cousins, so being born large is only part of the story.

We can learn the rest by studying their host galaxies. Like many others, our Milky Way contains traces of smaller, weaker galaxies it has devoured, and it currently is in the process of stripping material away from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. And that’s how it seems to work: two smaller galaxies merge, or a big galaxy munches a smaller one. The same principle appears to hold for supermassive black holes too.

Unlike a forest sustaining a small population of predators, most galaxies have only one supermassive black hole. If there is more than one, they tend to merge into a single larger black hole, a trick animals can’t do. (Territorial predators sometimes kill each other, of course, but the result of two lions fighting isn’t a single lion twice as large—though it’s a funny mental image.)

So there we have it: as smaller galaxies merge, so do their black holes. But how can we see that in action? Most galaxies in the nearby Universe, like the Milky Way, have “quiet” black holes: they aren’t actively feeding, so they aren’t bright like quasars. However, astronomers have spotted a few luminous black hole pairs, mostly in chaotic galaxies in the early stages of a merger.

That brings us back to the observation of a pair of black holes in the process of dismembering a star in a distant galaxy. This is the first time astronomers have identified a pair of black holes in a quiet galaxy, but even more excitingly, they are only separated by a distance about the width of the Solar System—much closer together than any other black hole pair we’ve ever seen. The researchers estimate it’s only about 2 million years (a mere cosmic moment!) before they merge entirely.

A pair of black holes in a single quiet galaxy isn’t enough. If we want to understand how the biggest black holes came to be, we need to see pairs at all stages: from separate galaxies, to the point where they are locked in orbit, to the final moments before they become a single black hole.

Like animal predators, these monsters may be rare, but they have their own beauty.