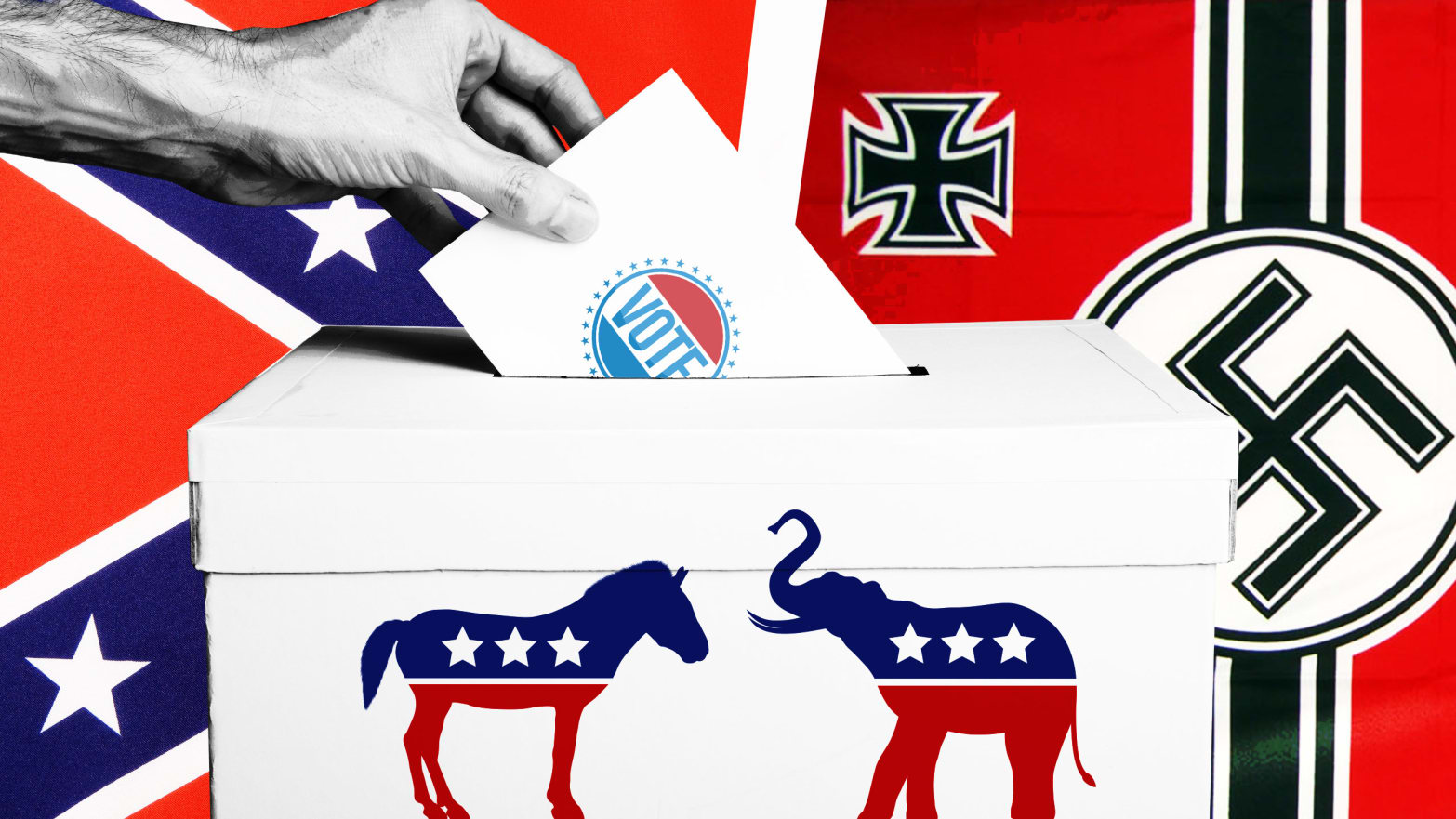

As the midterm elections approach, racist extremism is coming up for a vote.

More than a dozen Republican candidates this year have flirted with or endorsed white supremacy. They range from trolls, like neo-Nazis using long-shot campaigns as a loudspeaker for hate, to career politicians who’ve moved toward more open racism after Donald Trump’s election. While the most fringe candidates certain to lose, they may succeed in giving a bigger platform to white nationalist thinking and influence over the Republican Party. And while the GOP condemns those fringes, the career politicians who voiced similar views have largely avoided party backlash.

“There are more far-right candidates this year than we’ve ever seen, frankly,” Heidi Beirich, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, told The Daily Beast. “As to why that is, Trump's obviously the big issue here, right? He ran a campaign that traded in racism and anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, misogynistic rhetoric, and he won. I think in prior election campaigns, people who engaged in those tactics failed.”

Douglas Heye, a former Republican strategist and communications director, also connected some of the extremist trend to Trump.

“Some are being nominated, which raises their profile,” Heye said. “I think Trump has certainly brought some folks out on the fringe who wouldn’t be running otherwise.”

While some Republicans’ policies, like opposition to publicly funded housing and criminal justice reform, disproportionately harm people of color, Trump’s brand of right-wing populism brings a more overt racism, informed by his anti-Hispanic, anti-Muslim presidential campaign, and his false claims that the first black president was born in Kenya. His policies, including a ban on travel from several predominantly Muslim countries, separation of immigrant families at the southern border, and a crackdown on legal immigration, are in line with white nationalist goals.

Trump doesn’t have to be an outright white nationalist in order to enable them, said David Neiwert, a researcher on extremism and author of Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump.

“They seized onto Donald Trump, because he was their avenue” to the mainstream, Neiwert said. “That’s not to say Donald Trump is necessarily a white supremacist consciously. I don’t see any indication that he’s one of these white supremacist ideologues, but I certainly think he has absorbed a lot of white supremacist attitudes, and that’s not uncommon in America.”

Among these racist riding Trump’s coattails is former U.S. congressional candidate Patrick Little, a neo-Nazi who launched a bid to unseat Sen. Dianne Feinstein. Running as a Republican, he advocated for deporting Jews and praised Adolf Hitler on the campaign trail. He won 89,867 votes in his failed primary race in June. That’s just 1.3 percent of the overall vote for either party, but it’s still nearly 90,000 votes for a neo-Nazi.

Republicans disavowed Little, as they did with Arthur Jones, who won his uncontested congressional primary in Illinois in March despite claims to have been an American Nazi Party leader. Republicans also disavowed Paul Nehlen, who photoshopped Jews’ heads onto pikes during his failed bid for the House seat of Rep. Paul Ryan in Wisconsin. They disavowed Missouri state house candidate Steve West who won a contested primary despite going on a radio show to declare that “Hitler was right” about Jews.

There were more. Hawaii Republicans condemned white supremacist candidate Bryan Feste, and North Carolina Republicans condemned Russell Walker, who won his contested primary while declaring that “God is a racist and a white supremacist.” California Republicans condemned John Fitzgerald, an anti-Semite who won his uncontested congressional primary and recently appeared on two neo-Nazi podcasts. David Reid Ross, a Colorado candidate who won his uncontested state house primary, quit his campaign after media revealed his alt-right blog. National Republicans this July pulled their support from Seth Grossman, who is running for a House seat from New Jersey, after Media Matters reported on his praise for white nationalist writings.

Despite all of the disavowals, those candidates won more than 170,000 votes this year. With the possible exception of Grossman, none will likely take office in 2018. But that doesn’t mean their campaigns are harmless.

“When you run a campaign, whether you win or lose, you achieve greater name-recognition, you build supporter lists, you get your views aired on television or the radio,” SPLC’s Beirich said. “So there are reasons to run, even if you don’t think you can win. There’s also a downside for the rest of us Americans in the sense that these folks, win or lose, are pushing some pretty extreme ideas into the mainstream.”

Meanwhile, another set of less extreme candidates have coasted along without party condemnation.

In Virginia, U.S. Senate candidate Corey Stewart’s nomination set parts of the Republican establishment spiraling. With ties to neo-Confederate groups and the organizer of the deadly, Nazi-heavy Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville last year, Stewart reportedly prompted a wave of resignations from the Virginia GOP when he narrowly won his primary race with more than 136,000 votes. (This was after nearly winning the 2017 gubernatorial nomination.) But despite unofficially distancing themselves from him, the state party has not disavowed Stewart.

In Florida, Republican gubernatorial nominee Ron DeSantis has spoken at events alongside alt-right troll Milo Yiannopoulos, and led a political career heavy with racist gaffes like describing votes for his black opponent as “monkey[ing] this up.” He’s pushed dog-whistle conspiracy theories, including falsely implying Obama was a communist and claiming that ISIS might recruit from Black Lives Matter. He received more than 900,000 votes in the state’s Republican gubernatorial primary and is running practically tied against Democrat Andrew Gillum.

And then there’s a white supremacist whose views haven’t earned him party condemnation, but seven terms in Congress.

Steve King, a congressman from Iowa, has won seven elections to national office, all while pushing a nationalist, anti-immigrant agenda. But after Trump’s campaign, King’s rhetoric became undeniably white supremacist. During the 2016 election, King began openly championing Europe’s racist elite, including meeting extremist Dutch politician Geert Wilders.

“Wilders understands that culture and demographics are our destiny,” King tweeted in 2017, parroting a white supremacist talking point. “We can’t restore our civilization with other people’s babies.” He refused to backtrack on the tweet, and offered similar after multiple retweets of open white supremacists and neo-Nazis over the past two years. He’s tweeted white supremacist slogans and used them to praise autocratic leader Hungarian Viktor Orbán. He’s promoted white nationalist writer Peter Brimelow, placed a Confederate flag in his congressional office (he represents Iowa, which was part of the Union), and called undocumented immigration a “slow-motion holocaust.” He recently endorsed a white supremacist for mayor of Toronto, Canada

White nationalists falsely describe the growth of a non-white populace as “white genocide” or “replacement.” In September, King gave an interview to a far-right Austrian news site, the Huffington Post reported. During the interview, King voiced fears that Hispanic and Muslim Americans would come to overtake their white neighbors. He’s previously declined to answer whether he is a white supremacist or white nationalist, telling the Huffington Post that “I don’t answer those questions. I say to people that use those kind of allegations: Use those words a million times, because you’re reducing the value of them every time.”

Condemning all these racists on the party’s fringe is overwhelming, said Heye, the former GOP strategist.

“You condemn the rhetoric as much as you can. I think the challenge is, because there are so many examples of it, every time you see a Republican member on TV or walking down the halls of Congress, they’re asked to apologize for something else they didn’t do,” he said. “Do you have to condemn every time a party county committee chair says something? I’ve done a lot of it, but given there are thousands of counties in the country, is that being done every time and does that need to be done every time?”

Beirich, however, called the condemnations “completely lackluster.” Although some Republicans had spoken out, “for the most part, we’re not seeing Republicans across the board decry the current political system and extremist candidates running for office,” she said. “They’re not putting up a stopper to the stuff infiltrating our mainstream politics.”

Neiwert, the Alt-America author, went further.

“Moderates have been the problems all along. They’ve been enablers,” he said. “In the past, when we’ve pointed out the trends of right-wing extremism flowing into the mainstream Republican Party and the mainstream conservative movement, we’ve been dismissed as alarmist.”

It’s worth examining how moderate Republicans found themselves playing whack-a-mole with the extremist candidates popping up across the country.

While the GOP has been the home of a majority of white voters, especially in the South, for decades, the party has gone in a more extreme direction over the past decade, experts say.

“It’s a trend that’s been building within the Republican Party within the past 10-15 years. There’s been an increasing amount of traffic in ideas, agendas, and talking-points between right-wing extremists and mainstream Republicans,” Neiwert said. “It dates back to even before 9/11. But I would say it increased dramatically between the Obama years. It’s been reflected in the acceptance of very extremist ideas, mostly from the ‘patriot’ radical right: the patriot movement, the militia movement.”

Republicans should have drawn a line in the sand in 2010, said Virginia Republican Matt Walton, who previously ran for state office and worked on Gov. John Kasich’s presidential campaign. The 2010 elections marked the height of the fringe Tea Party movement, a right-wing populist movement that scholars say was partially fueled by anti-black racism after Barack Obama’s election as president.

“I think the party didn’t do a very good job stopping that rise early on and now you see where we’re at today.”

As Tea Party momentum died off, another, more explicitly racist movement made a play for control of the Republican Party. The alt-right, a loose coalition of fascist and white supremacist tendencies that coalesced on the internet during the 2016 presidential election, started dabbling in “entryism,” a political technique in which extremist groups infiltrate a sympathetic mainstream group and try to pull it to the fringes.

White nationalist Richard Spencer “in particular is very explicit about how they want to become the Republican Party and take over the Republican Party—they’ve been very clear about that,” Neiwert said. “White supremacists have been doing that for years. They want to be accepted into the mainstream again and have mainstream power.”Beirich highlighted the case of James Allsup, a member of a white nationalist group who had won a minor, uncontested seat in his county’s Republican Party, as The Daily Beast first reported.

“He’s been talking about how we can infiltrate the Republican Party from the right and shift it toward our position,” Beirich said. “Since Trump started running for office, [white supremacists] are talking a lot about politics, and a lot about entryism, and a lot about voting in a way they never did before, because they used to think the whole system was rigged against them, so what was the point?”

Although national and state Republicans disavowed Allsup, he has retained his seat, and local Republican leaders invited him to speak at an event where one defended him as the victim of “label lynching.”

The Republican Party’s post-9/11 drift, accelerated by fascist entryists and the election of Trump has set the GOP’s “underlying trend” toward “right-wing authoritarianism,” Neiwert said. That rightward lurch has freed incumbent politicians like King to turn more openly racist.

“Steve King was always a right-wing twit, a very far-right jerk, but it’s only been since Donald Trump was elected that he’s been willing to be more or less explicitly white nationalist,” Neiwart said, although as King’s policies go, “that’s the way he’s always tended anyway. That was always what underlay a lot of Steve King’s nativism and his Islamophobia: his white nationalist attitudes.”

The trend has also put moderate Republicans in a tough spot.

“You’ve got a broad part of the party that’s trying to look long-term here in Virginia, with the way it’s been trending more blue since 2009 statewide,” Walton said. “But at the same time, you’re getting a more far-right electorate coming out in primaries and conventions, which is forcing candidates to become more of an extremist when it comes to getting the nomination.”

Walton said he was not permitted to renew his state GOP members in 2016 because he did not support Trump in the general election, and that he’s experienced continued friction with the party over his refusal to back Stewart.

He’s not alone in his discomfort with Stewart, who has attended neo-Confederate events and led rallies with Unite the Right organizer Jason Kessler.

In August, a staffer for U.S. House candidate Thomas Oh sent an email to prominent Virginia Republicans saying he did not want his campaign materials displayed near Stewart’s.

“I personally met Mr. Stewart myself. Although I think he is a great person, I think it is best to let the two campaigns run separately,” the staffer wrote in the email, parts of which were first reported by the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “I have personally seen for myself at the local Farmer's Market and the Arlington County Fair yesterday, people pointing to Mr. Stewart's sign and saying out loud ‘Is that the Nazi? Never in my life will I vote for him.’ Thomas' sign happened to be directly next to his.”

If this is the year of extreme-right candidates, what’s to stop 2020 from looking the same? Trump’s election led us here, Walton said; the end of his administration might lead us out.

“I hope that by 2020 or even 2022, the fever has broken,” he said. “I think we need to see a change in leadership at the presidential level for the Republican Party for a full-on changing of the guard. I think it would be wise for the Republican Party, looking long-term, to take a hard look and make course corrections.”

But Trump isn’t the leader of the most extreme crowd; he’s a barometer for acceptance of their views, and vessel in which they can push those views further into the mainstream, Neiwert said.

“I really believe Donald Trump could disappear overnight and we’ll still have this problem for another ten years, maybe a full generation or longer,” he said. “Because it’s going to be systemic. It’s baked into our culture now in ways that other cultural trends aren’t.”

November 6 will be a referendum on the fringes: a chance for Americans to reject racist extremism, whether or not Republicans have denounced it as such.

“It’s sort of like the gates have been opened now and I don’t know when they’ll be shut,” Beirich said, “or if other people can follow Trump’s path and be successful. We’ll have to see.”