This is a story about the Three Little Pigs. A lot of dead oil workers. And British Petroleum.

From the minute the Deepwater Horizon offshore rig exploded, BP has hewed to a party line: it did everything it could to prevent the April 20 accident that killed 11 men and has been spewing millions of gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico ever since. Some critics have questioned the veracity of that position.

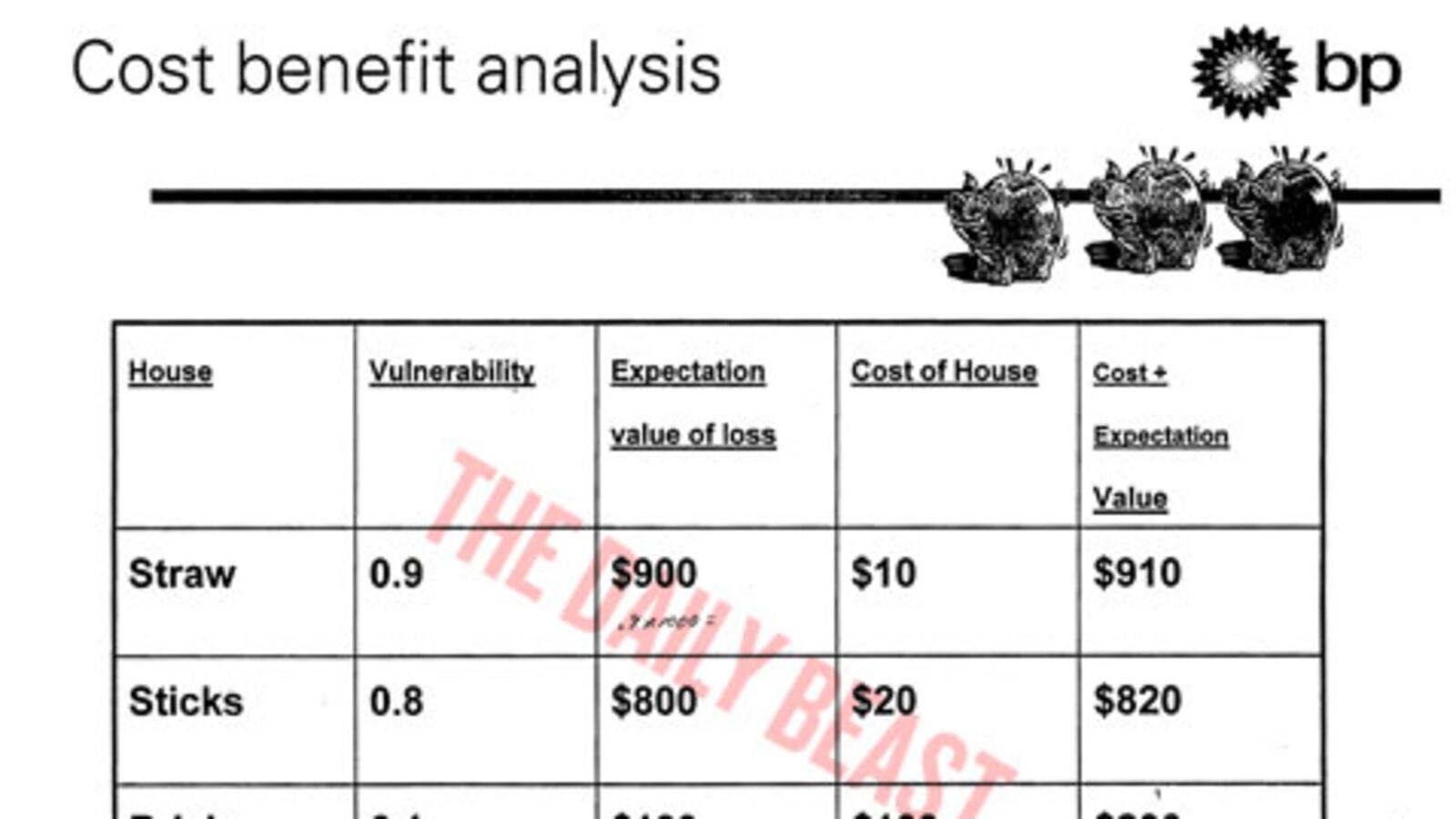

Now The Daily Beast has obtained a document—displayed below—that goes to the heart of BP procedures, demonstrating that before the company’s previous major disaster—at a moment when the oil giant could choose between cost-savings and greater safety—it selected cost-savings. And BP chose to illustrate that choice, without irony, by invoking the classic Three Little Pigs fairy tale.

EXCLUSIVE: This internal BP document shows how the company took deadly risks to save money by opting to build cheaper facilities for workers. The company estimated the value of a worker's life at $10 million.

A BP spokesman tells The Daily Beast that the company has “fundamentally changed the culture of BP” since the previous disaster, an explosion at a Texas refinery five years ago. But given that a $500,000 valve might have prevented the massive spill that is now threatening to devastate the Gulf of Mexico, one has to wonder.

Some context. In March 2005, BP’s Texas City Refinery caught fire. The explosion killed 15 workers, injured 170 plant employees and residents of nearby neighborhoods, and rocked buildings 10 miles away. Most of those who died were in trailers next to the isomerization unit, which boosts octane in gasoline, when it blew up.

Attorney Brent Coon represented families of the workers killed, and discovered internal BP documents that showed the oil giant had chosen to use trailers to house workers during the day, rather than blast-resistant structures, in order save money at the refinery.

Throughout his work on the case, Coon used a Three Little Pigs analogy to illustrate the cost/benefit analysis that he believed BP used to choose the less expensive buildings, with the trailers representing straw or sticks, versus stronger material the lawyer said should have been used. But whenever Coon brought up the fairy tale, he says that BP’s attorneys objected.

Then Coon received a set of documents through discovery.

“Right there we found a presentation on the decision to buy the trailers that showed BP using “The Three Little Pigs” to describe the costs associated with the four [refinery housing] options.” Says Coon: “I thought you’ve got to be f------ kidding me. They even had drawings of three pigs on the report.”

The two-page document, prepared by BP’s risk managers in October 2002 as part of a larger risk preparedness presentation, and titled “Cost benefit analysis of three little pigs,” is harrowing:

“Frequency—the big bad wolf blows with a frequency of once per lifetime.”

“Consequence—if the wolf blows down the house then the piggy is gobbled.”

“Maximum justifiable spend (MJS)—a piggy considers it’s worth $1000 to save its bacon.”

“Which type of house,” the report asks, “should the piggy build?”

It then answers its own question: a hand-written note, “optimal,” is marked next to an option that offers solid protection, but not the “blast resistant” trailer, typically all-welded steel structures, that cost 10 times as much.

At Texas City, all of the fatalities and many of the serious injuries occurred in or around the nine contractor trailers near the isom unit, which contained large quantities of flammable hydrocarbons and had a history of releases, fires, and other safety incidents. A number of trailers as far away as two football fields were heavily damaged.

Coon says that during the discovery process, he found another email from the BP Risk Management department that showed BP put a value on each worker when making its Three Little Pigs calculation: $10 million per life. One of Coon’s associates, Eric Newell, told me that the email came from Robert Mancini, a chemical engineer in risk management, during a period when BP was buying rival Amoco and was used to compare the two companies’ policies. This email, and the related Three Little Pigs memo, which has never before been publicly viewed, attracted almost no press attention.

The BP spokesman, Scott Dean, tells The Daily Beast: “Those documents are several years old,” and that since then, “we have invested $1 billion into upgrading that refinery and continue to improve our safety worldwide.” BP’s current chief executive, Tony Hayward, has consistently tried to distance himself from the track record of his predecessor, Lord John Browne, who resigned abruptly in 2007, after the company’s safety record and his private life both came under scrutiny.

The refinery explosion resulted in more than 3,000 lawsuits, including Coon’s, and out-of-court settlements totaling $1.6 billion. BP was also convicted of a felony violation of the Clean Air Act, fined $50 million and sentenced to three years probation. Last year, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration levied the largest monetary penalty in its history, $87 million, for "failing to correct safety problems identified after a 2005 explosion that killed 15 workers at its Texas City, Texas refinery."

So has BP changed since Lord Browne left? Does BP’s Three Little Pigs decision matrix apply to the Deepwater Horizon tragedy?

We know that the Deepwater well lacked the remote-control, acoustical valve that experts believe would have shut off the well when the blowout protector failed. The acoustic trigger costs about $500,000. How would that stand up to a similar “Maximum Justifiable Spend” analysis (especially when BP’s liability is officially capped at $75 million by federal law)?

Meanwhile, officials along the Gulf Coast continue to question whether BP has tried to cut corners on the containment of the oil gushing from the well. Just yesterday, Pensacola City Councilman Larry Johnson grilled BP’s Civic Affairs Director Liz Castro about why her company has failed to use supertankers, used to successfully clean similar sized spills in the Arabian Gulf in the 1990s, to assist with oil recovery.

“These tankers saved the environment and recovered approximately 85 percent of the crude oil,” Johnson lectured. “I think BP didn’t bring the tankers in here because it was more profitable to use them to transport oil.”

When Castro couldn’t answer technical questions, Johnson and his fellow council members banished Castro until she came back with people who could.

And while BP has repeatedly stated that it will pay all necessary and appropriate clean-up costs and verifiable claims for other loss and damage caused by the spill, the Florida Congressional delegation has repeatedly asked BP to place $1 billion in an escrow account to reimburse states and counties—instead the states have received $25 million block grants, plus $70 million to help with advertising campaigns.

While BP did announce a $500 million research project yesterday, to study the impact of the oil disaster on marine life over 10 years, that’s cold comfort to those worried about their livelihood. For all of BP’s pledges that it’s delivering a figurative brick house, a solid plan, to stop the leak, contain the spill and clean up the shore, too many people on the Gulf feel like they’re living in a house of straw.

Rick Outzen is publisher and editor of Independent News, the alternative newsweekly for Northwest Florida.