SEOUL—America’s adversaries are calculating how best to exploit American weakness at a time of deep and bitter divisions in the United States. China has announced its move on Hong Kong. Russia is increasingly confident as it looks at the debility of the United States under Donald J. Trump. Iran continues to edge its way out of the nuclear straitjacket it had agreed to with the Obama administration.

And then, there’s North Korea.

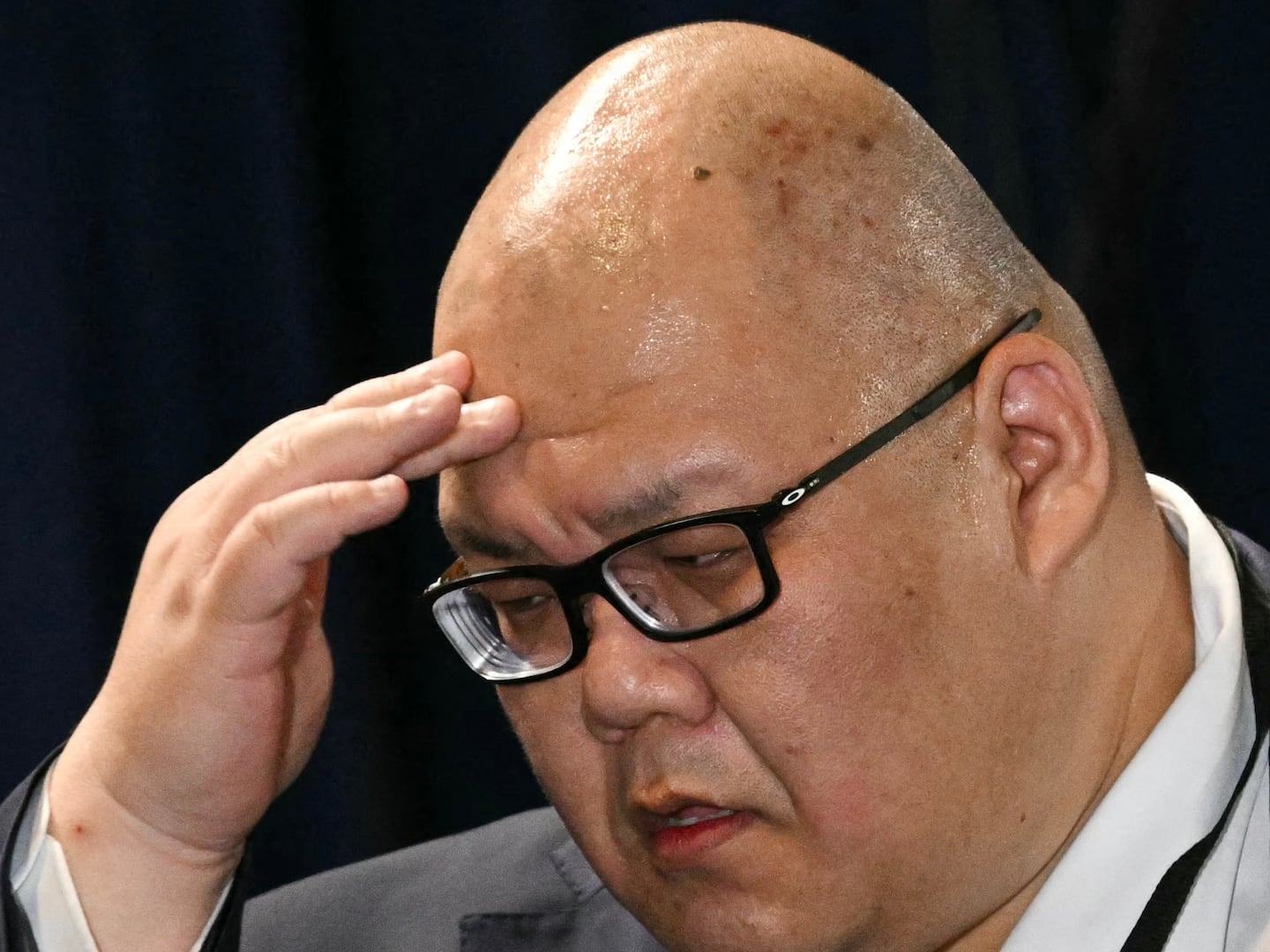

Kim Jong Un’s thinking may be as difficult to fathom as Donald Trump’s, but he’s watching carefully to see how the rest of the world responds to the American crisis and assess the optimal moment to show off his latest weapon of mass destruction. The risk is that the mercurial POTUS may decide a strong response to escalation of the North Korean threat would be a great way to distract from strife on his doorstep in the run-up to the presidential election in November.

Meanwhile Rodong Sinmun, North Korea’s leading mouthpiece has seized on America’s unrest, running photos of blazing scenes in American cities and reporting on protesters near the white House shouting “No justice, no peace” for the “lawless and brutal murder” of a black man by a white policeman.

Kim loves to keep his enemies guessing, but at a Workers’ Party session last month he talked up a “nuclear deterrent” and he looks likely to make good on his vow to reveal a “new” but hitherto undisclosed “strategic weapon” as promised at the dawn of the New Year.

U.S. analysts are worried Kim may feel the urge to show off his strength lest his adversaries, at home and abroad, suspect he’s bluffing.

Walter Sharp, a retired U.S. Army general and commander of U.S. forces in Korea from 2008 to 2011, expressed the concerns of his colleagues when he said he feared “we’re going to see a submarine here pretty soon that’s got a ballistic missile on it.” That would be what’s known as an SLBM, a submarine-launched ballistic missile, that a North Korean crew could fire at targets across the U.S from a sub menacingly close to America’s shores.

The United States has got to be ready with “the strong option” until North Korea agrees to “complete denuclearization and we have peace on the peninsula,” Sharp told a virtual meeting of the Korea Defense Veterans Association in Washington.

It’s been nearly six months since Kim first brandished the threat of another fearsome weapon capable of spreading death and destruction far beyond his borders, and many analysts believe he is eager to carry out a fairly spectacular test quite soon despite the risks.

Incredibly, that’s a prospect about which the Pentagon, at least until recently, did not seem overly concerned. It seemed a fundamental shift in strategic thinking about Kim had transpired since the days three years ago when he was testing intercontinental ballistic missiles and nuclear warheads and Donald Trump was taunting him as “rocket man.”

Policy hawks in those days loved to portray Kim as a mad tyrant who might actually launch nukes at the United States. Officially, the mood changed when Kim and Trump sat down in Singapore nearly two years ago. They got nowhere on nukes despite a lot of flowery language. Then there was the abortive Hanoi summit in February 2019 and, four months later, the impromptu get-together at the truce village of Panmunjom on the North-South line. Still no go on nukes.

Summits, optimistic pronouncements, and supposed “love” letters aside, it’s clear that Kim never had any intention of giving up his nuclear arsenal. So the administration has privately moved to a policy of deterrence, which means de facto acceptance of North Korea as a nuclear weapons power.

The change was evident in remarks last month by Drew Walter, deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear matters. Speaking at a Washington think tank, he talked up the urgent need for nuclear modernization to meet and exceed the rapid Russian and Chinese build-up, but said North Korea would be deterred by America’s existing arsenal. The North, he ruminated, was “not yet on the scale of some of our other nuclear-armed potential adversaries.”

North Korean SLBMs would fit into Kim's strategic picture of mutual deterrence, which already has reached a point of no return since diplomacy has gone nowhere and threats to eliminate North Korea’s arsenal by force only beg retaliation. If Kim could not quite wipe out the United States, he still could cause one hell of a lot of pain.

In effect the Pentagon is discounting North Korea as a serious nuclear power, treating it almost as an afterthought when talking about China and Russia. So Kim has to show he means business, which is what he was talking about at the recently convened central military commission of the Workers’ Party to discuss “new policies for further increasing the country’s nuclear war deterrence.”

Rodong Sinmun, the party newspaper, said the meeting was all about “putting the strategic armed forces on a high-alert operation.” Critical to the North’s readiness to test an advanced new model missile is that engineers by now have mastered the use of solid fuel, greatly reducing the time it takes to prepare the missile for launch.

“It is the first time for North Korea to use the term ‘high alert’ to describe nuclear forces,” Cho Dong-joon, professor at Seoul National University, told Dong A Ilbo, a leading South Korean newspaper. “Nuclear weapons can be used in a very short period of time.” Ryu Sung-yeob at the Korea Research Institute for Military Affairs was quoted as saying North Korea “is able to immediately launch a nuclear attack anywhere in Northeast Asia.”

North Korea “wants to go back to chapter one of the nuclear game,” said Choi Jin-wook, former director of the Korea Institute for National Unification. Kim faces one perpetual problem. “He seems to be in a dilemma,” Choi observed. “Nukes are not food that the North Korean people need badly.” But other analysts doubt that food security will deter Kim’s tests for long.

“They have to do it,” said Steve Tharp, who’s spent a career analyzing North Korea as an army officer and civilian official in the U.S. command here. “I learned a saying in Chinese many decades ago which applies perfectly to the North Koreans: ‘You can't teach a dog not to eat shit’—bad habits are hard to break.”

Just as important as the SLBM itself would be the submarine from which to fire the damn thing. A 3,000-ton sub capable of carrying three missiles is being built at the Sinpo shipyard on the northeastern coast, according to Yonhap, the South Korean news agency, and a 2,000-ton model already is afloat at the base, along with all the gear needed to blast away. The Washington think tank 38 North, which specializes in North Korea, fueled concerns by reporting that satellite imagery showed a strange 16-meter-long object near where the sub is under construction.

Then there are reports that some folks at the Pentagon are thinking maybe the U.S. should conduct its first nuclear test in nearly 28 years. Just the way to show off our great new stuff and scare the bejeezus out of the Chinese and Russians, goes the thinking. Such loose talk adds urgency to Kim’s stubborn drive to bolster his strategic deterrence by making good on his New Year’s “surprise.”

Walter didn’t help by saying the U.S. could conduct a nuclear test “relatively rapidly,” according to the military newspaper Defense News if Trump is so inclined. Conducting such a test at short notice might produce “limited diagnostics,” said Walter, but still might happen amid “widespread concern” about the way Russia and China “appear to interpret and adhere” to the terms of the comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty.

If the past is precedent, as long as the Americans entertain notions of a bigger, better nuclear network to counter China and Russia, Kim will factors his own nukes into the equation.

Rather than give short shrift to North Korea as a nuclear threat, Pentagon strategists may want to remember Kim’s view that his nukes are central to the global arms race.

“No doubt Kim understands the implications of renewed nuclear testing by the United States,” said Evans Revere, a former senior U.S. diplomat in Seoul and Washington. The call for increased “nuclear deterrence,” said Revere, “could be his way of signaling Washington that he has cards he can play.”

In fact, North Korea has already tested an SLBM, albeit from an underwater platform, not a submarine. Kim witnessed the launch last October of an early version that soared about 600 miles above the earth’s surface and flew 300 miles not far from his enormous villa complex near the east coast port of Wonsan.

And SLBMs are not his only weapon of choice. He has also developed intercontinental ballistic missiles, ICBMs, that could be launched from North Korea and hit anywhere in the United States. His freeze on testing such weapons came only after he was sure they worked.

A report by Joseph Bermudez, long-time analyst of satellite imagery, focused on North Korea’s nuclear and missile sites, exposed a new facility near Pyongyang airport that was “almost certainly related to North Korea’s expanding ballistic missile program.” The report included imagery of a facility big enough for any “known North Korean ballistic missiles and their associated launchers and support vehicles.”

That report “suggests that Kim has been talking about an ICBM that can deliver nuclear weapons to attack the U.S.,” said Bruce Bennett, who’s been studying North Korea’s military and political moves for years at the Rand Corporation. But Kim knows that an ICBM launch would be a massive provocation. Trump has tried to minimize the threat of shorter range ballistic missiles, which Kim has tested repeatedly, as more localized “theater” weapons. But their launch from submarines would be as dangerous for Americans as ICBMs—or more, since there would be less warning time for U.S. missile defenses.

“I am guessing [Kim] will continue with theater missile tests as opposed to a nuclear weapon test through the U.S. election,” said Bennett. “He might try an SLBM as part of that testing process” though “he would not want to test an ICBM until after the election—that would be taking a big risk of a serious U.S. response.”

Several analysts see a North Korean SLBM test as highly likely and imminent. The looming second anniversary of the first summit between Kim and Trump adds urgency to Kim's quest. The logic here is, since the U.S. did not live up to its side of the agreement, whatever that was, then he's justified in defying the Americans and testing whatever he wants to test.

It was at the Workers’ Party session on December 31, as KCNA reported at the time, that Kim “confirmed that the world will witness a new strategic weapon to be possessed by the DPRK,” the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. “We cannot give up the security of our future just for the visible economic results,” Kim told the meeting. “We should more actively push forward the project for developing strategic weapons.”

Bruce Klingner, a former CIA official who specializes in northeast Asia at the Heritage Foundation, notes Pyongyang at the party plenum in December threatened its new weapon “in the near future” after the U.S. refused to yield to the North’s demands on sanctions. Typically, the North “takes time to produce official policy statements,” as Klingner observed.

“Experts are uncertain what the new weapon will be,” Klingner said. “North Korea has already demonstrated it has hydrogen (thermo-nuclear) weapons” in its last nuclear test in September 2017. Logically, bigger and better delivery vehicles could be next.

Toward that end, Klingner sees the SLBM as one of several new weapons that North Korea may test. A new SLBM has been “in development” but is “unlikely to have sufficient range to reach the continental U.S. from North Korean waters."

But Kim’s obvious objective would be to take the subs and their deadly arsenal far outside his own waters, and far closer to the United States in what could become an extremely dangerous game of cat and mouse for American defenses.

As eager as Kim might be to order another missile test, the most recent Workers’ Party meeting was also about morale-boosting.

“With sanctions and the pandemic cutting North Korean trade, the Kim regime has less material benefits to distribute among loyalists,” said Leif-Eric Easley, international relations professor at Ewha University in Seoul. “When you’re running low on cash, you can still dole out shiny medals and fancy titles. Kim appears to be rewarding those who have delivered successful weapons tests”

Among those getting new titles were Ri Pyong-chol, formerly commander of the North’s air force, who was named vice chairman of the commission as a reward for overseeing the North’s nuclear and missile program, and Pak Jong-chon, chief of the North’s artillery, named a vice marshal.

“Further promotions might hinge on the long-awaited 'new strategic weapon’ that may be a ballistic missile submarine,” said Easley. “North Korea is set on strengthening its claimed nuclear deterrent irrespective of U.S. policy, but Pyongyang is likely to use some trumped-up threat from Washington as an excuse for its next major test.”

Robert Collins, formerly an intelligence analyst with the U.S. Forces Korea command and author of authoritative studies of the North Korean ruling establishment, was not impressed by the promotions. “This is not a leadership strengthening act,” he said, “just a reward.”

One name that went unmentioned was that of Kim’s younger sister, Kim Yo Jong, often seen as a successor if he finally succumbs to his many physical issues, ranging from obesity to diabetes.

“Little sister,” said Collins, “has not the slightest idea about the military.”