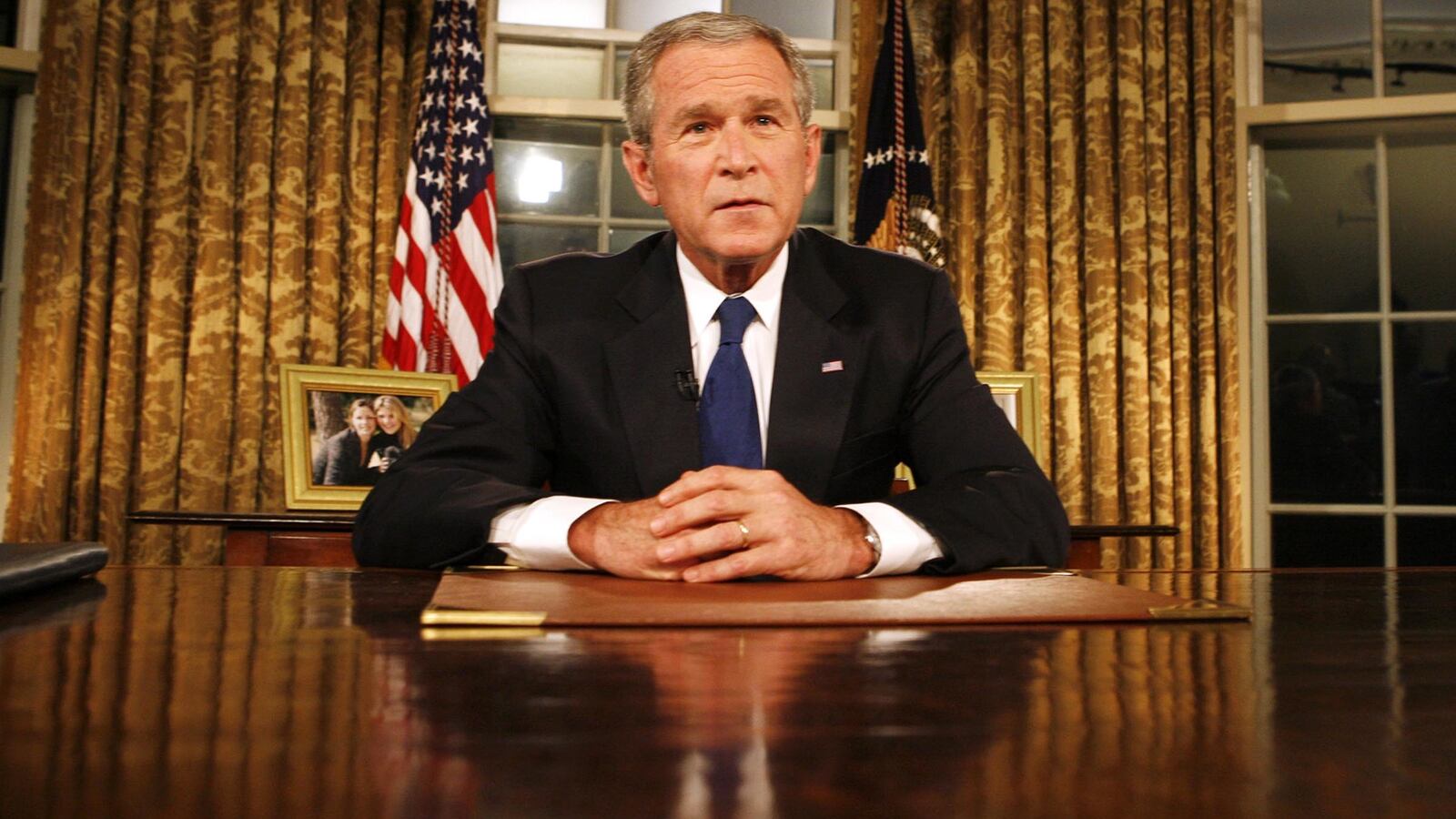

When it opens on Christmas Day, Adam McKay’s dynamite movie Vice will rain on the Bush parade, as it should. It promises to lay bare the yawning gap in competence between 41 and 43.

During the cascade of eulogies to George Herbert Walker Bush it was almost as though his son’s presidency had never existed, that it was being wished away by the solemn assembly of the nation’s elders in the national cathedral on Wednesday. Vice just scored the most nominations in the Golden Globe awards, six, including best comedy, and is a hot Oscar contender.

There was another reason to forget. The contrast between the elder Bush’s temperate skills in statesmanship and Trump was so explicit that it hung there in the atmosphere without needing words; so much odium is attached to this White House that there is no room left in our memories for the calamity of W’s administration.

We have, in fact, reached a puzzling state in our affairs when a movie can deliver a more sobering blast of history than any other tribunes.

The villain of Vice is one of the most malevolent figures in our recent history, Dick Cheney. Cheney is shown to emasculate W so completely in his first term that his accumulation of executive power amounts to a slow-motion coup by the vice president and his cohort of neocons.

McKay, talking to Jonah Weiner in the New York Times Magazine, said “Cheney is one of the most brilliant bureaucratic infighters in history, but he knew how to do this stuff so that you barely knew it was happening.”

Trailers for the movie show Christian Bale, who became obese to play the role, and had the help of amazing facial prosthetics, in the fateful minutes when he plays Bush into accepting him as his pick for vice president—after Cheney, assigned to make a search for candidates, has come up dry. (Cheney, who had been Bush senior’s defense secretary, had been attached to W’s transition team as a trusted family adviser.)

Sam Rockwell, as Bush, chews away at a fried chicken leg and guilelessly enthuses over Cheney’s brilliant idea.

But McKay isn’t just pursuing tone-perfect mimicry and physical resemblance. He’s diving into the Shakespearean depths of Cheney’s lust for power, with Lady Macbeth-style collaboration from his wife Lynne, played by Amy Adams. It will likely be compared to Doctor Strangelove (where Peter Sellers was similarly transformed into a bald demon) in the unnerving force of its satire.

Strangelove was allegory, not history, building on the behavior of some of John F. Kennedy’s hawkish generals at the time of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, the closest the world came to nuclear Armageddon in the Cold War. Vice is satire but hews far closer to actual events. Of course, the more Cheney becomes the indispensable villain to the story, the fewer become the Bush fingerprints at the crime scene.

McKay drew on two journalistic sources, Barton Gellman’s Cheney biography, Angler, and Jane Mayer’s The Dark Side. Gellman’s book grew from a series of investigative pieces he did, with Joe Becker, for the Washington Post in 2007, which for the first time unpeeled the true scale of Cheney’s influence.

That date is significant. It was near the end W’s second term, when the wreckage of Cheney’s work, human and geopolitical, was strewn across the Middle East, smoking like a pyre. Beginning in the wake of 9/11, Cheney had led W into giving priority to the wrong target, Saddam Hussein, rather than Bin Laden. As a result, Iraq was turned into a charnel house while Iran was left free to become the regional power that it was never able to be as long as Saddam was there. It doesn’t get dumber than that.

So it took at least six years to do the reporting that for the first time revealed how Cheney had set the agenda of regime change (one that Bush senior had adamantly rejected, foreseeing its consequences, at the end of his swift victory in the first Gulf War) and, leading W by the nose, had carried out.

Those six years were a lasting indictment of access journalism in Washington.

Cheney and his apostles, Paul Wolfowitz and Richard Perle, remaking the world according to their dark intent, suckered reporters into buying the basis of their policy, that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction and intended to use them. Their most successful con was getting the New York Times to swallow the “aluminum pipes” story where harmless imports were portrayed as formative steps in acquiring nuclear weapons.

Cheney, the draft-dodging chicken hawk, acted virtually unchallenged on network shows as pitchman for his dark scheme. He exhibited a telltale verbal trick, saying “in point of fact” when about to deliver a falsehood, reminiscent of Nixon’s flickering eyelids. There was no apology for waterboarding prisoners—Cheney said it wasn’t illegal and it wasn’t torture, and it worked. (FBI interrogation experts said it didn’t.)

On Comedy Central, Jon Stewart—often more vigilant than the Washington press corps—introduced a segment named “You Don’t Know Dick.” How true that was.

The New York Times and the Washington Post have since learned from their errors of omission and commission, to become the investigative powerhouses they now are.

But how deep can reporters ever get into deep government?

The First Amendment isn’t funded. Sustained forensic reporting needs deep pockets at a time when newsrooms have been shrinking. And administrations of both parties like to keep a lot of their activities secret.

In 2013 Leonard Downie, a former executive editor of the Washington Post, released a report on behalf of the Committee to Protect Journalists that said that President Obama had waged a war on leaks that was “the most aggressive since the Nixon administration.” Downie said Obama officials had severely limited the release of information that was essential to holding them to account.

David Sanger, chief Washington correspondent for the Times, said “This is the most closed, control-freak administration I’ve ever covered.”

Two of the most consequential pieces of journalism of that time did not involve any deep investigative journalism or any major funding: They were the release by WikiLeaks of 720,000 secret documents from the State and Defense departments and the series of revelations from Edward Snowden about the massive reach of surveillance conducted by the NSA and CIA.

The Times, the Post and The Guardian carefully checked and curated Snowden’s devastating picture of what seemed like a police state in the making—certainly the surveillance ranked in its paranoia with that of the notorious East German Stasi. Yet this and the WikiLeaks data dump, which revealed grotesque human rights violations in Iraq, were drivers in hardening Obama officials against the idea of being more transparent.

Hillary Clinton, who had voted for the Iraq war, joined hardliners in saying that Snowden, if he returned from Russia, should end up in jail.

Since then, of course, WikiLeaks has been sullied by its role in leaking Democratic National Committee emails hacked by the Russia’s military intelligence service masquerading as Guccifer 2.0.—although the orchestrator of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, denies the source was Russia.

What has changed significantly is that no editor would any longer trust Assange as either a source or collaborator. He’s far too much enjoying his role as an international man of mystery, leaving the impression that his main allegiance is to himself.

Journalism is in an even more challenging environment now. The First Amendment makes no distinction in terms of freedom to operate between Breitbart News and the Washington Post. Fox News is basically a captive mouthpiece of the Trump administration. Malfeasance in the White House has supplanted neocon plots as a target subject.

And, irony of ironies, agencies that were once players in the Cheney dark arts, like the CIA and NSA, now seem to be among the good guys as they endure the president’s continued insult stream. This halo effect has also embraced former spooks like Michael Hayden, James Clapper and John Brennan who, affronted by Trump’s assaults on the whole intelligence community, have rounded on him.

The new model of how to conduct a deep forensic investigation is Robert Mueller. There has never been a more leak-proof operation. In his rigor and judicial ethic Mueller is making a new kind of point about the limits of journalism: nobody knows how much he knows until he chooses to announce it in scrupulously prepared indictments.

Parsing Mueller has become a reporting mission much like those that used to be carried out when covering the Kremlin in the days of the Soviet Union. Every scrap of information is seized on for significance, while the whole picture remains inscrutable.

At least in this administration we don’t have to go looking for a hidden hand. The hand on the wrecking ball is clear. Instead of a sinister schemer there is a silver-haired cypher as veep happy to bide his time and keep his nose clean in a confederacy of grifters.

The chicken hawk’s wings were clipped in W’s second term. The president who had been deaf to his father’s cautions—indeed, he had pointedly disregarded them—realized, too late, that his own legacy would be contaminated, possibly beyond repair, by Cheney.

There were worries that Cheney had undergone a serious personality change. Brent Scowcroft, one of George H. W. Bush’s most trusted military advisers, complained, to a New Yorker reporter: “The real anomaly in the administration is Cheney. I consider Cheney a good friend—I’ve known him for 30 years. But Dick Cheney I don’t know anymore.”

But there was another Bush problem. They began to think like a dynasty. To them the presidency acquired the attractions of a 19th century hereditary monarchy. With W gone Jeb decided that 2016 would need another Bush. After all, the Clintons thought in the same terms.

Who in their right mind could really believe that the only talent pool for presidents could exist in two families? The conceit was delusional but, in the case of Hillary, all-devouring. Her nomination was locked up. It seems so Boomer, a generation with a consuming sense of entitlement and, in this case, name recognition was deemed sufficient to qualify.

Luckily there isn’t much chance of a Trump dynasty. If the current indicators are true, Junior is likely to end up in premises far more confined than the White House.