American pop culture would be unrecognizable had a short Jewish kid from New York’s Lower East Side not fished a magazine out of a gutter one day after school.

Jacob Kurtzberg was a thug by default. His immigrant family paid $12 a month to live in a Suffolk Street tenement, where violence was as ubiquitous as poverty. For protection more than sadism, Kurtzberg’s friends were gang members, engaging in what they called “climb-outs,” the art of chasing or being chased up fire escapes to get money or settle scores.

“You fight on the roof,” he would reminisce, “and you fight all the way down again.” Kurtzberg’s early ambition in life was to be a corrupt politician, reaping the downstream benefits of violence, rather enduring than its upstream difficulties.

But walking home from P.S. 20 sometime in the late 1920s, Kurtzberg saw a piece of trash that, mysteriously, compelled him.

“It was a rainy day, and it was floating toward the sewer in the gutter. So I pick up this pulp magazine, and it’s Wonder Stories, and it's got a rocket-ship on the cover, and I’d never seen a rocket ship. I said, ‘What the heck is this?’” Kurtzberg recalled, near the end of his life. He hid the magazine under his pillow, since “if the fellows caught me reading it or doing anything academic out of school,” Kurtzberg might have to run up a fire escape.

Some superheroes get their powers from archeological specimens. Others are transformed by magic words, or genetic secrets, or medical experiments. A rocket ship on the cover of a magazine turned Jacob Kurtzberg into Jack Kirby, King of Comics, the man who created the visual grammar of American pop culture.

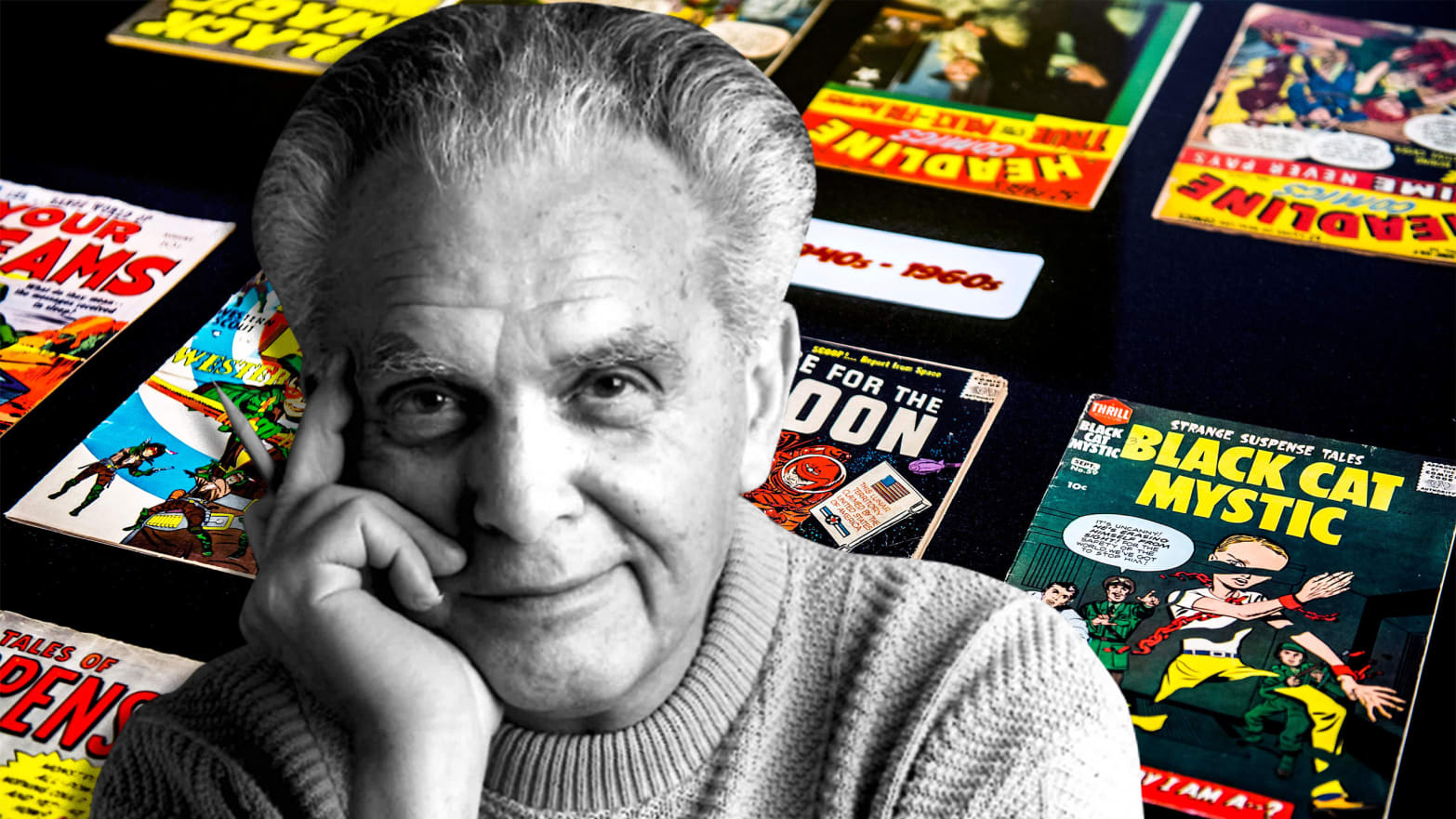

Kirby, whose 100th birthday is tomorrow, is the greatest American artist whose work never hung on a museum wall. Calling Kirby the undisputed master of superhero comic books honors his unparalleled co-creations: Captain America, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, the Avengers, the Black Panther, the New Gods.

But listing the roster of his characters understates his influence beyond the comics page. Star Wars owes a significant amount to Kirby’s Fourth World space opera. Refracted through the prism of George Lucas, Kirby’s Mark Moonrider becomes Luke Skywalker. Kirby’s indescribable cosmic energy, the Source, becomes the Jedi’s Force, with its Dark side conspicuously echoing Kirby’s evil-made-flesh, the tyrant-god Darkseid. Doctor Doom is the first draft of Darth Vader, the green cloak dyed black and deathly face-plate upgraded to a sci-fi helmet.

The ink from Kirby’s fingerprints leave marks in the unlikeliest parts of the 20th century. He seethed at Roy Lichtenstein recontextualizing—Kirby preferred to say stealing—Kirby’s figures, faces and action scenes for the gallery set, turning him into the highbrow sensation that Kirby never was. When the CIA needed a fake sci-fi movie to cover an operation to free westerners hiding in Iran, immortalized in the Oscar-winning film Argo, Kirby drew the storyboards.

Kirby’s figures, fluid and frenetic, expanded the limits of their art form. His contemporaries in the early 1960s drew heroes and villains battling stiffly in the middle distance. Kirby’s figures gestured out at the reader, with perspective-distorted fists swinging at the panel borders. Like their co-creator, Kirby’s superheroes fought on top of New York’s buildings, establishing a comic-book trope for the ages. “I feel like the father of a hundred acrobats,” Kirby once told a Vanderbilt University audience.

Yet Kirby did not primarily think of himself as an artist. He called himself a storyteller, a designation suggesting he was less interested in draftsmanship than in the new worlds behind his brushstrokes. “How well a man draws cuts no ice with me,” he told assistant Steve Sherman in 1975, “if what he’s trying to express comes out vague and choppy.”

Yet Kirby’s genius was forged in the crucibles of war and injustice.

Two years after debuting Captain America in March 1941—punching Hitler in the jaw—Kirby was drafted. He served in Patton’s army as a scout, an exceptionally dangerous mission taking him into Nazi-held territory in France and Belgium so he could reconnoiter for the division behind him and, of course, draw maps. He would recall Germans using anti-armor weapons to pin him down, their shells overhead “like high-speed mosquitos” as he took cover, firing his rifle as if it could make a difference.

“Our radios barely worked and the telephones were almost as bad; the lines were always getting cut. In many ways I think that war was the last human war,” he would tell an interviewer. “We were just a bunch of guys with guns.”

Private Kirby contracted frostbite on his feet and lower legs before Patton pushed to Bastogne, sending him back to New York, wheelchair-bound, on a hospital ship. The taciturn Kirby later remarked, “Listen, I was doing all right compared to most of the other guys”—including those whose money he won during card games on the trip home.

Kirby’s metier was people in leotards punching each other, ranging from the super-soldier who decked Nazis while wearing an American flag uniform to the cosmic avatars waging an eternal, Wagnerian conflict. But he was unsentimental, even angry, about the devastation he saw in Europe.

“There is nothing that you would call ‘romantic’ about war,” he observed. “Sure, in the movies and on television they paint a great picture of the fellowship that it creates. I’ve seen war bring people together, but I can tell you that the cost is extremely high: not just in terms of lives, but the human spirit. I think that we are diminished by war; our character as a race is somehow reduced by each war that we allowed to happen… We will have to find another way to settle our differences. It is in that way that I would say that war is senseless.”

Kirby’s anti-war sensibilities could cut against the prevailing cultural trends. By the mid-1960s, Kirby was at the height of his powers, having revolutionized comic art by co-creating most of the first wave of Marvel Comics. As much as Kirby’s partner-turned-adversary, writer/editor Stan Lee, pitched himself to America as a youth-culture bard, Lee vigorously policed Marvel’s material to avoid giving offense, particularly as America incrementally ratcheted up its involvement in Vietnam. When a reader suggested in a letter column that Marvel write to deployed servicemembers, Lee annotated it to say, “this notice is not intended as an endorsement on our part of any specific policy regarding the war.”

Kirby, by contrast, “didn’t like that war,” he later said. “I thought it was crazy. And of course, that had an effect on a generation of young people who just couldn’t understand it.”

As much as Kirby hated war, he accepted the necessity of confronting injustice—along with self-defense, the only justification for conflict Kirby could endorse. From the very first image of Captain America, Kirby used his art in ways both glaring and subtle—well, as subtle as superhero comics can be—as tools for social justice.

Captain America was not an instant, universal American icon in 1941. Kirby and his co-creator Joe Simon, both Jewish, received death threats. A biographer, longtime Kirby assistant Mark Evanier, described Kirby getting a phone call from someone urging him to come down to the lobby of Timely Comics (the company that would become Marvel), where three thugs wanted “to show him what real Nazis would do to his Captain America.” Kirby, Evanier recalled, “rolled up his sleeves and headed downstairs.”

The Nazis—cowards then as now—had already fled.

By the Marvel era of the ’60s, comics were a homogenous industry. The vast majority of creators were Jews and Italians in New York who had difficulty finding steady work in the more upscale world of advertising. But Kirby possessed sufficient empathy not to want to make comics aimed at white people. The first appearance of the Black Panther, in Fantastic Four #52, can be cringeworthy, as it’s a book by two white creators about an African hero. But the Wakanda Kirby and Lee presented was a technological wonder whose ingenuity is shown outclassing that of white super-scientist Mister Fantastic by the third page.

“I realized I had no blacks in my strip,” Kirby later explained to interviewer Gary Groth. Kirby’s language is an unfortunate product of his era, but he was expressing shame at the realization that he hadn’t made his creations sufficiently inclusive:

“My first friend was a black! And here I was ignoring them because I was associating with everybody else. It suddenly dawned on me—believe me, it was for human reasons—I suddenly discovered nobody was doing blacks. And here I am a leading cartoonist and I wasn’t doing a black. I was the first one to do an Asian. Then I began to realize that there was a whole range of human differences. Remember, in my day, drawing an Asian was drawing Fu Manchu—that’s the only Asian they knew.”

Kirby hardly presaged Afro-Futurism, but his cultural palette was broad. If the Aztecs had designed a massive stationary machine, it would resemble the Ruler of the Earth from Journey Into Mystery #81. Indeed, the design sensibilities of Central and South American cultures before the European conquest formed a consistent wellspring of inspiration for Kirby throughout his career. Most famously, Marvel’s devourer of worlds, Galactus, appears in Fantastic Four garbed in armor and a headdress borrowing richly from Aztec and Mayan costumes.

Jack Kirby never received his due. Although by the 1970s he was one of the highest-paid artists in comics, Kirby’s co-creations have made Marvel and its parent, Disney, billions of dollars (particularly now that Disney also owns LucasFilm). His family settled a copyright dispute with Marvel in 2014 for undisclosed terms.

Kirby’s legacy is incalculable. Another comic-book legend, Frank Miller, eulogized him after his death in 1994: “We will never see his like again. No single artist will replace him. No art form can expect to be gifted with more than one talent as brilliant as his.” His brilliance, his bravery and his principles provide yet another reminder that genius can emerge like a rocket ship from the gutters.