One hundred years ago today was the occasion for James Joyce to publish a piece on “The Centenary of Charles Dickens.” He was not kind; as the sign on David Copperfield’s back says, “Take care of him. He bites.” “He hardly deserves a place among the highest,” Joyce wrote. The books were “diffuse, overloaded with minute and often irrelevant observation.” This from the author of the forthcoming Finnegans Wake, the mother of the overload!

But Joyce had a point, never mind that palpable huff in his tone—the essay was a bother for him, written for the purpose of passing Italy’s teaching exams. Dickens’s position as a “writer’s writer” is not quite secure—at least not to the “great writers.” George Orwell was perfectly miffed: “Why does anyone care about Dickens? Why do I care about Dickens?”

Surely, beyond the silly arbitrariness of a 200th anniversary, there must be reasons that his works are selling joyfully, that BBC TV and Radio have been commandeered by programs on him, including a new three-part Great Expectations, and biographies march into stores one after another—Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s Becoming Dickens, a number of handsomely illustrated coffee-table books, and, best of all, Charles Dickens: A Life, by Claire Tomalin, whose sentences are as fizzy as Dickens’s own.

Consider the fuss we still make over Little Nell and Little Dorrit, Wemmick and Sam Weller, the Micawbers and the Gargerys, Mr. Creakle and Serjeant Buzfuz. Regarding the creative powers of Dickens there is no debate.

If that’s not enough to convince the Orwells of today, you have only to look around you: at the thriving indifference of wealth and the unhinging of labor; the dejection of the jobless and Newt Gingrich’s demands for child labor; the dread of a blackening horizon and the people of Zuccotti Park. Dickens was a writer who, in every book, grappled with the big, modern machine called capitalism, with all its successes and failures. Nearly all the people who find their way into his world are there because they struggle as hangers-on to a flawed system—burglars and bailiffs, craftsmen and children, Plornishes and Peggottys.

As much as the critic Edmund Wilson claimed that Dickens was not interested in politics, it is politics that most Dickens critics write about. It is no accident that those appraisers who dealt so squarely with his legacy, from G.K. Chesterton to Christopher Hitchens, were themselves so very politically minded. They—all of them—have something to say about his shortcomings as a novelist: everyone knows the E.M. Forster judgment of Dickens’s characters being “flat” as opposed to “round,” though even he had to admit that “the immense vitality of Dickens causes his characters to vibrate.” But very seldom do they disparage the morals of his stories, or disagree with his attacks on English institutions, even as they downplay their significance in the construct of his canon. The notable exception was, of course, Orwell, who thought him too middle-class. But who could keep up with Orwell’s radicalism? Apparently not even Karl Marx, who wrote that Dickens “issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists, and moralists put together.” It does not make him right—as Wilson pointed out, “Dickens was sometimes actually stupid about politics.”

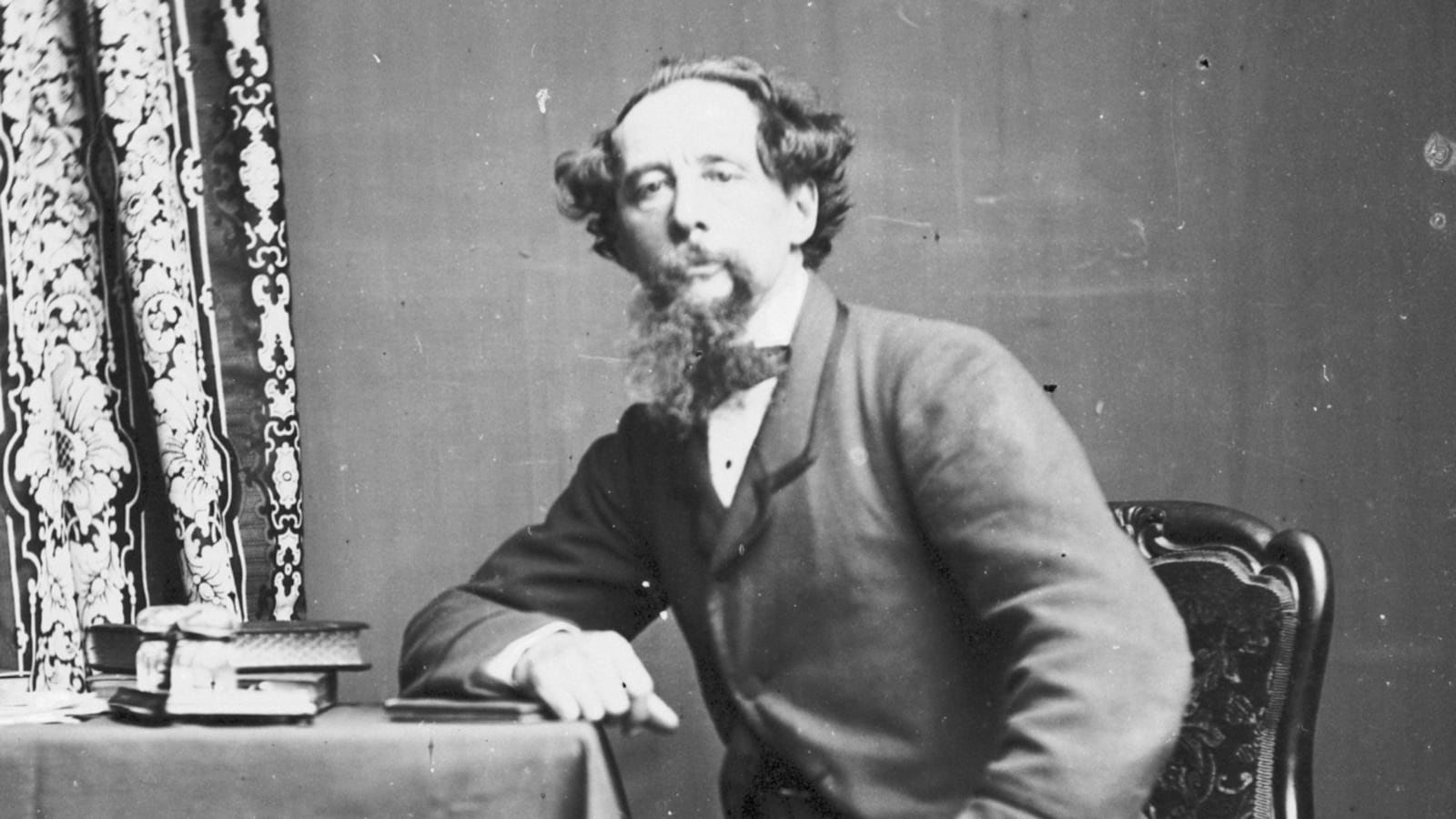

Born in Portsmouth on Feb. 7, 1812, Dickens soon moved with his family to Chatham, until his feeble father, John, relocated to London under financial difficulties, then was sent to the Marshalsea debtor’s prison. This landed 12-year-old Charles in “the blacking factory,” affixing "Warren's Blacking" labels to small bottles, again and again, for 10 hours a day. It didn’t help that, once he was released from work after a few months, the schoolmaster at his “academy” was a “bloated mahogany ruler.” All the familiar elements of a Dickens plot are now in place. We have only to add that young Charles did not grow to become an angel. He announced his separation from his wife on the front page of a magazine he edited. He had a poor woman arrested for saying dirty words in the street. He publicly defended Edward Eyre, the governor of Jamaica, who in 1865 so brutally crushed a rebellion that John Stuart Mill and Thomas Huxley wanted him tried.

But never was there a more tenuous claim than expecting novelists to marry their actions with their works; if they did, no one could ever invent. Dickens’s words unequivocally condemned inequality and poverty in a time of ambivalence. There were problems with the free-market economy, and inextricably, an empire was tipping toward decline. Joyce, apart from being right about, well, everything, also pinpoints the best about Dickens: “The life of London is the breath of his nostrils … the colors, the familiar noises, the very odors of the great metropolis.” Joyce might have preferred Tolstoy or Zola, but did anyone before or since better capture the contradictions and sins of a great capitalist city?

It is absurd to think we can “learn” to tackle these issues by reading Dickens. That is not why we read novels—certainly not to solve complex and current problems of politics. A consequence of 200th birthdays—this time not so arbitrary—is that Dickens's dying in 1870, at the age of 58, means that no one alive today even knew of his time, whereas your grandparents might have overlapped with a centenary. Dickens has passed into the somewhat ancient. He is now a bit of an old curiosity, though we try to grasp onto the thread that connects us to him. Among some of the most fascinating commemorations is a facsimile of the manuscript for Great Expectations published by Cambridge University Press. To see his perhaps greatest novel opened out line by line makes you want to cheer out loud. His letters are also on view at the Morgan Library in New York, and, of course, at the Charles Dickens Museum in London. To grab at those links—facsimiles! letters!—is to hear the sound of being outmoded.

Dickens has gone through his apotheosis and risen very much into the classics. The problems of capitalism have not. Similar overcast days are with us again. How will we do this time?