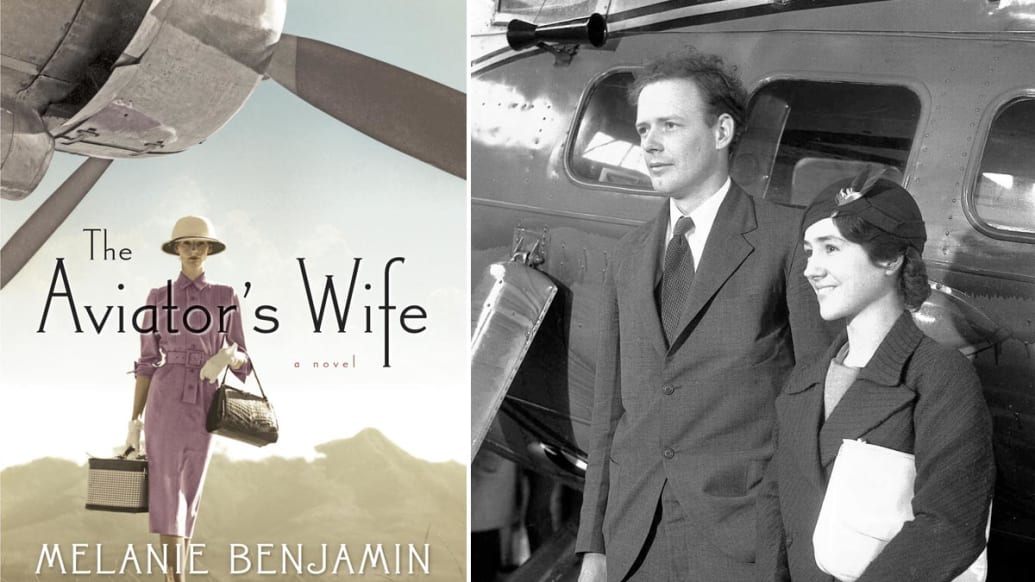

In August of 2003, three German siblings, Dyrk, Astrid, and David Hesshaimer made a startling announcement at a press conference in Munich: Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974), America’s national hero after he became the first pilot to fly across the Atlantic in 1927, was their father. As evidence, the three Hesshaimers, then ranging in age from 36 to 45, whipped out more than 100 love letters that the aviator had sent to their mother, Brigitte, from the late 1950s until his death in 1974. A DNA test taken a few months later confirmed their assertion. This revelation turned out to be just one of many secrets that Lindbergh had kept from the world. As the trio noted in a book that they co-authored with a German journalist the following year, Lindbergh had also engaged in long-term relationships with two other German women, with whom he had fathered four other children.

This German biography made headlines all over Europe, but fell on strangely deaf ears in America. As Dyrk Hesshaimer told me in an interview that I conducted in Munich last fall in order to complete the Lindbergh chapter in my forthcoming book, America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation, no American publisher wanted anything to do with it. In fact, except for a couple of articles in The New York Times immediately following the initial revelations a decade ago, the American press has said nary a word. Surprisingly, in this age of TMZ, when almost every date of Taylor Swift gets wall-to-wall coverage, the over-the-top sexual escapades of one of the biggest celebrities in American history have hardly registered.

Enter Melanie Benjamin, whose previous historical novels have focused on Alice Liddell and Mrs. Tom Thumb; her recently released bestseller, The Aviator’s Wife, constitutes the first attempt by an American writer to integrate this chapter of Lindbergh’s life into an understanding of the man and his legacy. Though A. Scott Berg’s Pulitzer Prize–winning biography, Lindbergh (1998), remains the definitive portrait, it cited a “compulsive need to travel” as the main reason for Lindbergh’s frequent absences from the suburban Connecticut home that he shared with his American family—his wife, Anne Morrow, and their five surviving children—during the last two decades of his life. According to Berg, Lindbergh strayed just once, with a young Filipina beauty whom he met on one of his numerous trips to her country in the early 1970s.

Told through the voice of the Anne, a talented wordsmith who authored numerous books, including the bestselling proto-feminist classic, Gift from the Sea, Benjamin’s novel charts how this 20th-century American housewife “leaned in,” as Sheryl Sandberg might put it, to gain more power on the homefront. In the early years of her marriage, the Smith College English major did everything she could to be her husband’s “good girl,” even agreeing to abandon their infant son, Charles Jr., in order to serve as the co-pilot on Lindbergh’s plane trips around the world. In March of 1932, right before the infamous murder of the 20-month-old Charles Jr., Anne muses, “I’d gone from college to the cockpit without a chance to decide who I was on my own, but so far, I was only grateful to Charles for saving me from that decision, for giving me direction when I had none.” But two decades later, as she begins to realize that her rarely-at-home mate is a prisoner to his own eccentricities—his list-making, his cruel practical jokes, and his aloofness—she breaks “free from his spell.” While Anne chooses to stay married, she moves into an apartment of her own on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and begins a satisfying affair with the family doctor.

To provide connective tissue to Anne’s discovery of her own identity, Benjamin mines Lindbergh’s secret sexual adventures. Since Benjamin has not read the German biography, she neglects to mention any of the juicy details such as the Superman-like alias, Careu Kent, which he used in Germany, or his specially designed blue Volkswagen (his “love bug”), which he drove during his frequent visits there. Her novel begins at the end of Lindbergh’s life when Anne discovers love letters to the three German “mistresses.” In a handful of short chapters interwoven with the chronological story line, Benjamin keeps coming back to these moments in 1974 when Anne grapples with her initial shock and fury. (As Benjamin acknowledges in an Author’s Note, these scenes are fabricated because there is no archival evidence to support the claim that Anne ever learned about his other families). A few minutes before his death, an exasperated Anne demands an explanation, “To have those other families. For the last time, Charles—why?”

While Lindbergh never responds, Benjamin offers an explanation. In her Author’s Note, she argues that “the kidnapping truly broke Charles Lindbergh beyond repair; it can be seen as the explanation for all that he did after—the long absences, the tyrannical behavior toward his children….And finally the secret families.”

The “Crime of the Century” certainly did traumatize Lindbergh. As the German biographer reports, Lindbergh was so concerned with losing his first German child that he personally took the infant’s fingerprints and footprints and insisted that mistress number #1 tote them around at all times (in case they were ever needed for identification purposes). However, it is a stretch to view this tragedy as the main cause for his lifelong character disorder. From birth on, Lindbergh had difficulty connecting with others. As an adolescent, he developed crushes not on girls, but on machines; his first one was on “Maria,” the family’s Model T Ford.

For the “Lone Eagle,” women were not so much other human beings, with whom he could build intimate relationships, as machines, whose services he needed rather frequently. His four “wives” weren’t even enough to keep him sexually satisfied. Unmentioned in Benjamin’s novel are any of this sex addict’s other lovers such as the Filipina or the stewardess, nearly 40 years his junior, whom he met for trysts in exotic locales all over the world in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as biographer Susan Hertog reported in Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (1999).

The love of his life was not a woman, but The Spirit of St. Louis. As Anne Lindbergh notes after one of her first meetings with the aviator in Benjamin’s novel, “He patted the plane in the same manner as a cowboy caressing his favorite horse. I almost felt as if I was intruding on an intimate scene.” But while his obsessive love of machines caused him to be a lousy husband, it was precisely what he needed to march right into the history books.