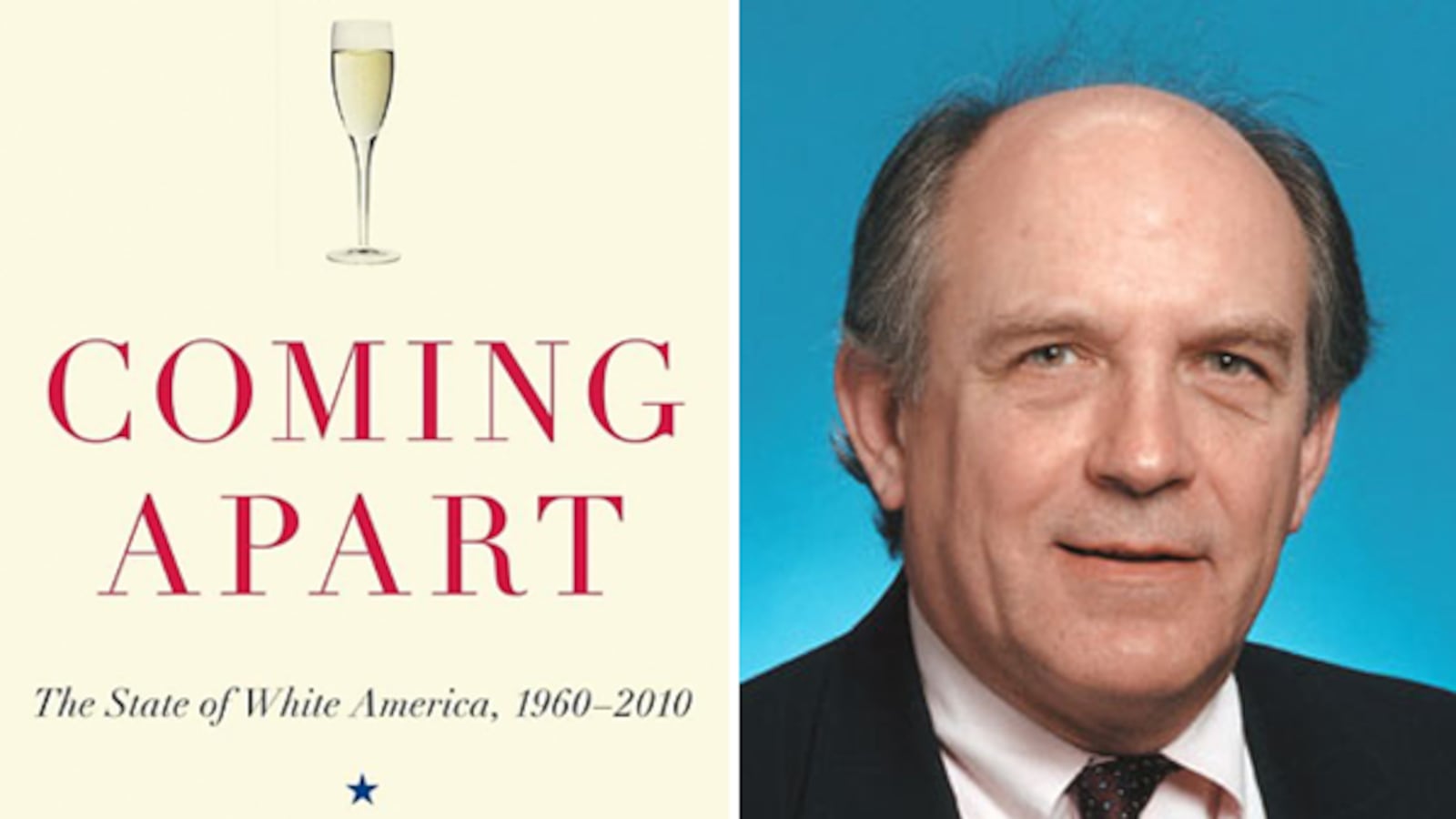

In Coming Apart, Charles Murray enters the polarizing debate about economic inequality in American society. Murray rejects the pieties of the political left and right alike. The rise of an economic elite that garners an ever larger share of income and wealth, according to Murray, does not, as some on the left assert, reflect a system rigged to favor the rich, but neither is the economic divide as inconsequential as some on the political right seem to assume.

Although Murray draws heavily from social-science data—described in multiple appendices that span nearly 100 pages—Coming Apart is more than anything an expression of Murray’s own distinctive ideological commitments, a worldview that has made him a hero to some and anathema to many.

While Murray rightly attributes the economic divide to an evolving labor market in which advanced education and skills have become more economically valuable, he wrongly views it through a prism in which one’s success depends wholly on one’s cultural values and genetic endowment.

The economic divide is a social divide as well, as the elite tend to cluster among themselves in selected cities—San Francisco; Austin, Texas; Washington, D.C., New York—and in particular in what Murray characterizes as “super ZIPs,” neighborhoods where the elite are most insulated from those on the other side of the divide. The elite socialize and form friendships and marriages almost exclusively within the group, so much so that they become disconnected from the less fortunate members of society.

The socioeconomic divide is apparent in family patterns. Highly educated women marry later in life than their less educated counterparts and don’t have children until they do so. The disadvantaged, in contrast, often have children without marrying, and when they do marry are less likely than their more affluent counterparts to stay married. Children bear the costs of these differences in familial stability and parental maturity.

Murray views the decline in marriage and the rise in unwed childbearing as but one example of a broader cultural decline. As the elite sequester themselves, in this account, deviance overtakes the poor, deprived as they are of the salutary cultural influence of their cognitive superiors. The new lower class, according to Murray, has also strayed from the traditional American virtues of industriousness, honesty, and religiosity, exacerbating their disadvantage and diminishing their likelihood of thriving in the new economy.

Generational change entrenches the economic divide. Because members of the elite tend to marry people like them, their children are likely to become part of the elite as well. The children of the disadvantaged, in contrast, will find it more difficult to succeed. As their disadvantage deepens, this new underclass can only become more angry and disaffected, viewing with scorn the elites who seem to (and do) rule over their lives.

The bleak future that Murray envisions is an ever growing welfare state, in which the tax dollars of the highly compensated yet socially isolated elite support those who are unable to compete in an increasingly demanding global economy. The inevitable expansion of the welfare state will further undermine the values on which individual success (and happiness) depend and will eventually approach collapse, as its economics become unsustainable. Murray’s hope is for a Great Awakening of sorts, in which the elite cease to subsidize failure by exempting others from responsibility, and instead more forcefully implore the disadvantaged to live by traditional American values.

As one example of his overreliance on culture to explain social change, Murray too readily attributes the divergence in the childbearing patterns of the poor and the elite to cultural differences between them. In fact, the divergence in the family patterns of the affluent and the disadvantaged is more a matter of economics than culture. Cultural attitudes toward marriage have unquestionably shifted during the past half century, but those changes encompass everyone. Premarital sex and cohabitation may have been rare half a century or more ago, but now they are common among all groups. Marriage was once a necessity; now it’s a luxury, and as with any luxury, the affluent are better able to afford it. Poor and working-class people, research has shown, view marriage similarly to their more affluent counterparts, but the disadvantaged are less likely to attain the level of economic stability that makes marriage both more likely and more enduring.

Murray also errs in reducing educational attainment and professional success solely to genetic endowment. Murray imagines that all smart people are born that way, and that only those (like African-Americans, according to Murray) who are genetically inferior struggle in the new brains-based economy.

Yet those members of the cognitive elite that Murray lauds certainly know better. When they have children, they devote untold hours, money, and energy into getting their children into the “right” schools, and not simply the right colleges. The quest to provide their child an educational advantage goes all the way back to expensive preschool and continues through primary and secondary school. The places that Murray highlights as hubs of the cognitive elite—New York, Washington D.C., San Francisco, and Silicon Valley—are also places where many affluent parents spend more than $20,000 a year for kindergarten! Why spend so much money on education if, as Murray supposes, it doesn’t enhance a child’s cognitive performance? The reality that is obvious to every parent is that while nature matters, so too does nurture. The better the environment, the smarter a child will become.

Parents’ efforts to guarantee their children the best possible education also contribute to the socioeconomic isolation that Murray laments. Parents are so obsessed with school quality that they reliably bid up the prices of homes in neighborhoods with good schools. Those who cannot afford to buy in are left in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods with low-performing schools.

Governmental policy thus contributes both to achievement differences and to the social divide between the affluent and the disadvantaged. What if our nation committed itself to ensuring that every school be a good school and that every child receive a top quality education? Social mobility would increase, economic inequality would likely decrease, and there would be less pressure for ambitious parents to buy into any particular school district.

Murray rightly identifies the challenges of economic inequality and family instability. But rather than attempt to reform the culture of those who are struggling, we’d do better to reform the governmental policies that provide their children so many fewer opportunities than the children of the elite. In order to not come apart, our nation must do more to make real the promise of opportunity at the heart of the American story.