In a world convinced that peril looms and that the entire financial world is built on fraud and illusion, it is neither chic nor popular to laud those who are keeping the dogs of anarchy at bay. Yet that is precisely what the central banks of the world are doing today.

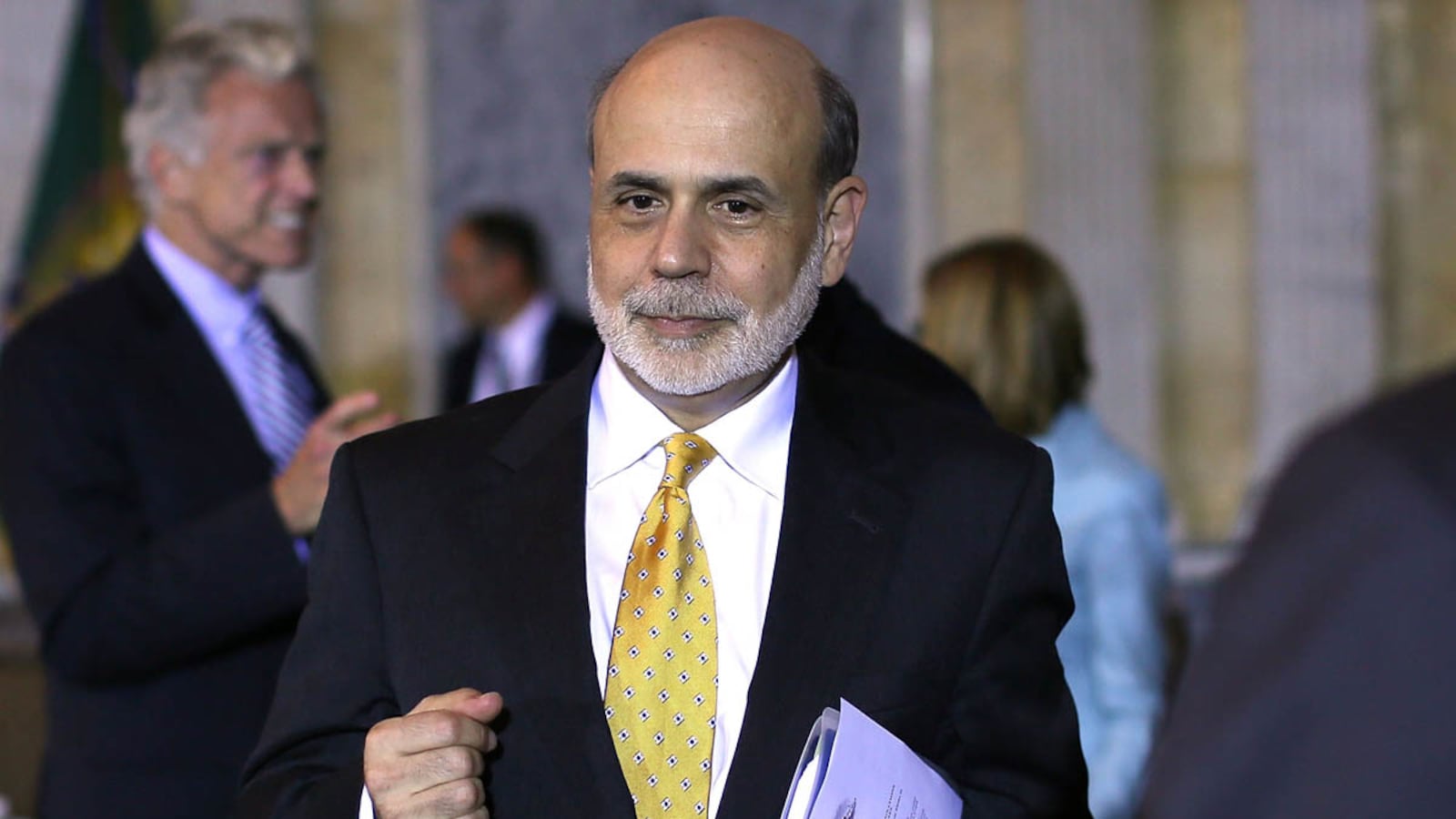

It may be that they are doing so by default and that their efforts only seem Herculean because of the Lilliputian efforts of so many elected officials and private industry. Even so, in the past week alone, the dual actions of the European Central Bank, headed by the uncharismatic yet intense Mario Draghi, and the Federal Reserve, led by the equally uncharismatic and diligent Ben Bernanke, have ensured that while the global economic system may not thrive for some time, it will at the very least not collapse.

And let us not understate how important that it is. Stirring, no; vital, yes. Last week Draghi unveiled a wide-ranging policy to purchase the debt of euro zone countries, to be a buyer of last resort. Today, the Federal Reserve unveiled a program to keep interest rates at or near zero until 2015 and to buy up to $40 billion a month of mortgage bonds and related securities in order to lower rates and ensure that the market is buoyed. Stocks markets have reacted with predictable glee: equity investors like it when banks guarantee that someone will buy. Bond markets also responded, sending the dangerously high rates for Italian and Spanish bonds back towards 5 percent—well out of the danger zone.

But the larger impact is as much psychological as financial. Central banks understand that the confidence of financial markets rests on shaky foundations, especially after the shocks of the past four years. They also recognize that to date, elected officials have done a lousy job of dealing with structural unemployment and an equally poor job coming to grips with the issues of too little revenue and too much spending. They have responded by acting as elites—a dirty word today but one that need not be. They have acted as the proverbial guardians of the temple and done what is in their power to make sure that at the very least, the financial system, held together globally by thin bonds, does not implode.

You can already hear the howls of protest: bankers are idiots, just as they were before the Great Depression, slavishly devoted to academic theories and addicted to easy money. They may have forestalled collapse now only to guarantee that it will be that much more severe when it does inevitably happen. There will be artificially low interest rates, violations of the free market, and looming, perilous inflation. Republicans in this election season already have attacked the Fed for these and other perceived sins, and immediately pounced on the decision today as more of the same ineffective medicine.

Some of the old criticisms have merit: central bankers are wedded to theories and can be both arrogant in their belief they can tame the system and mistaken in the choices they make to maintain it. But for the moment, they are doing society a needed a service. The Tea Party would prefer “burn baby burn,” for the rotten edifice to implode so that a new one can be built in its place. But deep in the DNA of central banks is an awareness that the real collapse of financial systems lead to political chaos, global anarchy, and, in the 20th century, war. That may seem far-fetched today, but I doubt we want to test the extent of our social resilience if the system indeed unwinds, as it threatened to do in 2008-2009 and briefly again in the fall of 2011.

The recent moves of banks bolster the financial system. The effect on daily life can be immediate. Pension plans go up, mortgage rates stay low, credit can flow more easily, and people are not assaulted with the immediate fear and anxiety that preclude other actions. These moves also place the onus for what to do next and how to address the structural issues firmly in the laps of elected officials, and in the U.S. on Congress and the White House. Central banks understand that they cannot fix fiscal issues; they can’t solve the long-term issues of health-care costs, defense budgets and Social Security along with tax rates. They can’t get private or public companies to hire domestically. They can only make sure that that financial system functions fluidly.

So now it is up to the people, to elections and elected representatives, and to companies large and small, to innovate and to solve problems. The record for Congress and for legislatures everywhere in recent years is not inspiring. The record of companies large and small is more so. We may soon be revisiting these crises, in Europe if the economic swoon isn’t reversed and in the United States if we remain frozen in place. But for now, central banks, the Fed especially, have done what they can, and for that we should be thankful.