BELGRADE, Serbia—“You win the game when you get there, when you make it,” says Fawad, a 17-year-old Afghan I met in a refugee camp near the Croatian border. “There” typically means Germany or Sweden, and the Game is the act of illegally crossing borders, largely played by unaccompanied minors fleeing their homelands.

“You have the train game where people hide in shipping containers,” he says, “You have the forest game where people sneak through the trees. Then you have the truck game where you wait for truck drivers near the border to fall asleep or pass out drunk in their cabs. Then you open the container at the back of the truck and sneak in. There is even an airplane game where you use fake passports, but that is the most expensive.”

The game operates like a deranged version of snakes and ladders. Refugees and migrants consider themselves the chits. Smugglers, whom refugees and migrants pay at different points to help them, are facilitators but also dangerous and sometimes exploitative operators. Police and border agents are the villains, and when players are caught, they’re sent back to the last country on their journey.

“When the police catch you the game is over.” Fawad tells me.

On 19 March 2017 in Serbia, two adolescent boys stand on a wooden beam leaning against a dilapidated warehouse building at an informal squatter settlement known as The Barracks, in Belgrade, the capital.

Courtesy UNICEFThe Game is afoot across much of Europe, with asylum seekers attempting irregular movement onto the continent. The Game exists because EU member states have largely failed to provide refugee and migrant children with practical, safe, and legal options for them to reach their destinations. And Europe’s failure has left these children in harm’s way because the Game carries the greatest of risks—exploitation, detention, abuse, injury, even death—for those who play it.

Humanitarian organizations are warning that warmer spring will likely bring a significant increase in the number of refugees and migrants attempting to enter Europe through irregular border crossings. Countries like Italy and Serbia are already reporting higher numbers of arrivals over the first quarter of 2017. UNICEF is especially concerned about unaccompanied minors traveling to and through Europe in record numbers (a five-fold increase since 2010-2011) and the dangers they face both in transit and upon arrival—children playing the Game are the most vulnerable to its dangers.

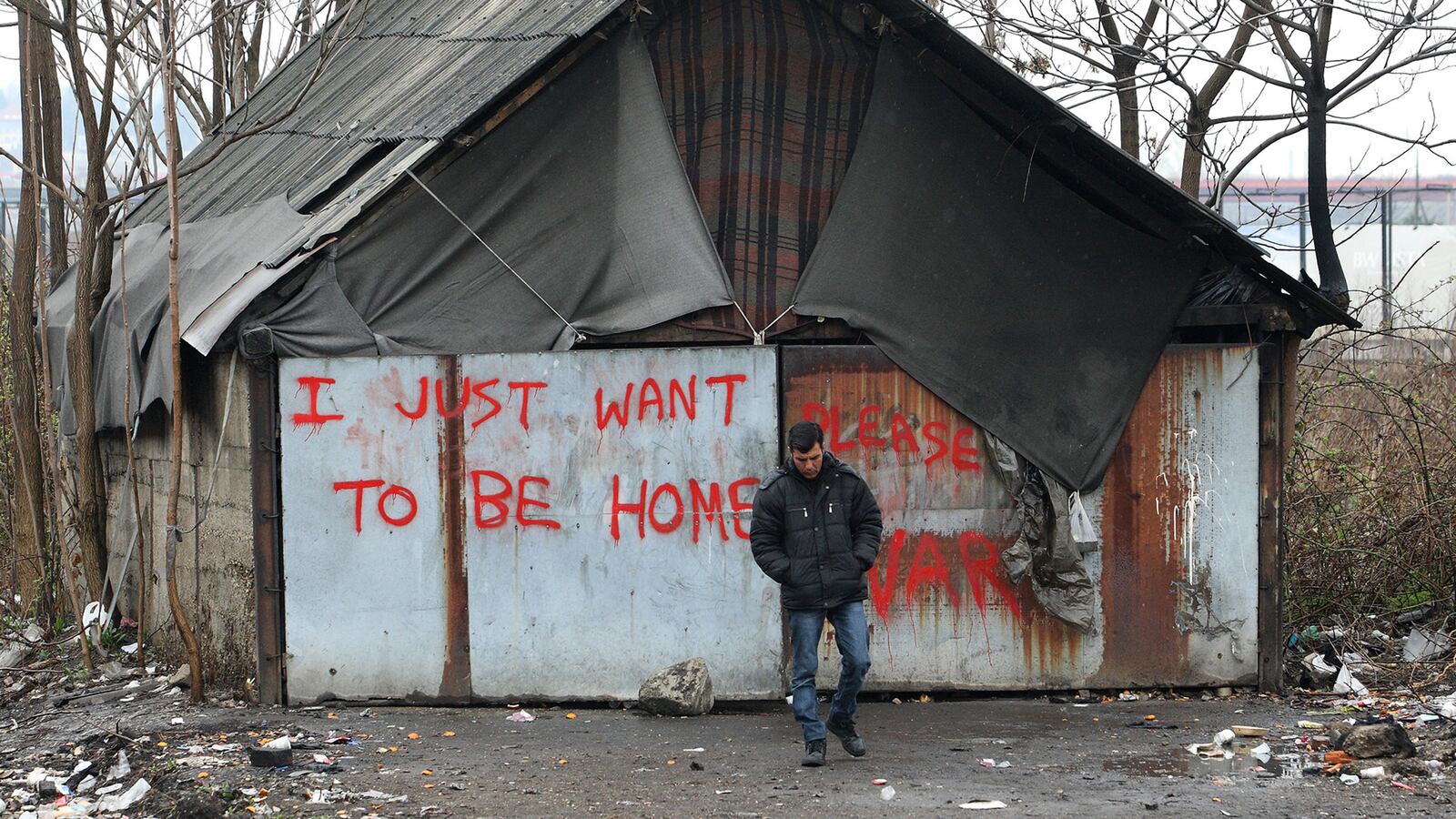

One of the Game’s nerve centers is the Barracks—an abandoned series of warehouses in central Belgrade where approximately 1,200 men and boys are sleeping rough. They refuse to register with asylum services because that means they could be moved out of the city from which they can most easily try sneaking into the EU countries of Croatia and Hungary. Smugglers operate relatively freely inside the Barracks, making asylum seekers even more reluctant to move to an official shelter where such illicit connections would be would be greatly reduced.

Conditions in the Barracks are abysmal—one of the reasons authorities are currently working to clear it. There is virtually no access to safe water and sanitation and people sleep on filthy mattresses or mats. Acrid smoke fills the air inside as people light fires for warmth or cooking. Unaccompanied boys are at heightened risk of exploitation and abuse here, given that they are sheltering with single men without adequate monitoring and protection. There have been news reports of sexual exploitation and abuse of minors. The Barracks is no place for children, and their presence there only underscores Europe’s failure to protect them.

Men and boys use the Barracks as a staging ground for the next level of the Game, sneaking into Hungary or Croatia. Most will fail several times at this, typically caught by border police and pushed back, before they successfully make it through. Failing this level of the Game usually means a beating at the hands of border police.

Sixteen-year-old Zobair, an unaccompanied minor from Afghanistan squatting in the Barracks, had his knee badly dislocated by border police a month ago when he tried to cross into Hungary. “The smugglers cut the wire in the fence and they (the police) caught us after a few meters. They sprayed us in the eyes (with pepper spray). Then I didn’t know what was happening. But then a policeman hit my leg with a stick. It was so painful. They dislocated my knee.”

Despite the danger, Zobair will try again to cross the border. “We are forced to try to cross again. It doesn’t matter how I feel about it. This has been a very tough journey. I don’t have any option, but to stay strong.”

Zobair’s story is sadly common, with many other unaccompanied minors reporting similar experiences of violence during failed levels of the Game.

Khaled, also 16 and from Afghanistan, says the Hungarian border is very dangerous. “When we go to the border, it is very hard. The police beat us. They beat us with police sticks each time we try to cross. I’ve tried to cross four or five times. We know this is illegal but we don’t have another way. They don’t have to beat us because we are human too.”

Last week, Khaled tried his luck crossing into Croatia with a group of other unaccompanied minors. The result was another failed attempt. “We walked eight hours (through the forest) into Croatia, but the police caught us and drove us back to the border. One by one when we got out of the police car, they beat us with sticks and sent us back.”

In Greece, most of the approximately 50,000 refugees and migrants stranded there have played the Game at one time or another.

On 19 March 2017 in Serbia, several youths warm themselves and a man dries an item of clothing at a small wood fire, inside a dilapidated warehouse building at an informal squatter settlement known as The Barracks, in Belgrade, the capital.

Courtesy UNICEFAhmed, a 17-year-old unaccompanied minor, played the Game from Syria to Greece. “My father is a lawyer and he knows smugglers. It cost $1,500 to get from Syria to Turkey. We walked across the border with other families through the trees.”

Ahmed and his younger brother tried at least four times to cross from Turkey into Greece before they were successful. “At first, we tried to cross over land, but it didn’t work. Sometimes, it was too cold in the forest. Sometimes, we had to run away from the Turkish police. The first time we tried, we were actually arrested by the Greek police and had to spend the night in jail before they sent us back to Turkey the next day.”

Eventually, Ahmed and his brother changed strategy and tried to enter Greece by sea. They paid smugglers who helped them and eight other people cross by boat from Antalya. The group landed at 4 a.m. on the Greek island of Castilorizo, a remote island close to the Turkish coast. There was no one on the beach to welcome them.

Ahmed says that during the trip he would read Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist to cope with stress and anxiety caused by the Game. “I liked its message that anything is possible in life,” he says.

For the past four months, Ahmed and his brother have been staying at a shelter in Athens. “When I was in jail, I thought life was terrible, but then I came here and everything was good.”

As evidenced by the EU-Turkey agreement dramatically curbing irregular border crossings from Turkey to Greece and a similar proposal to halt smuggling from Libya to Italy, much of the EU is actively trying to stop the inflow of refugees and migrants. But closing borders only perpetuates the Game and ups its deadly stakes, especially for the children who play it. Because without safe and legal pathways to migration, desperate people will take desperate measures to get to where they need to go. Asylum seekers don’t stop moving because of these policies, they just accept greater risks.

States must do a better job of protecting child refugees and migrants, particularly unaccompanied children, from exploitation and violence. This starts with making sure that children don’t have to cross borders illegally simply because they are seeking a better life.

Fawad is increasingly frustrated by his circumstances in Serbia, not knowing when or whether he might be granted reunification with relatives in the U.K. It’s no surprise then that he is considering crossing illegally into Croatia because of his growing despondency and boredom in the refugee camp at the Croatian border.

“You can’t imagine our life here,” he says. “Every day is the same. So boring. It is like jail. I think I am growing crazy because I am starting to forget the things I have learned in life. Not knowing what will happen causes great stress.”

He knows the risks involved, but nevertheless, he says, “We have had to face risk all the way from Afghanistan. This is no different. You have to risk in life. You have to risk in the Game.”

Christopher Tidey is an emergency communication specialist for UNICEF, focusing on the refugee and migrant crisis in Europe. For the past two years, he has traveled extensively throughout the “Eastern and Central Mediterranean routes” as part of the UNICEF response in support of refugee and migrant children.