I can’t stop laughing.

I can’t stop laughing because the man I consider one of the greatest writers alive, the man whose homoerotic scenes—notably devoid of graphic sex—are so subtle that they make me tear up and bring forth forgotten aches and memories of missed chances, is shocking me by doing his best impression of an anonymous sex scene in queer culture’s yesteryear of back rooms and public toilets. The writer who is best known for not going there is going there.

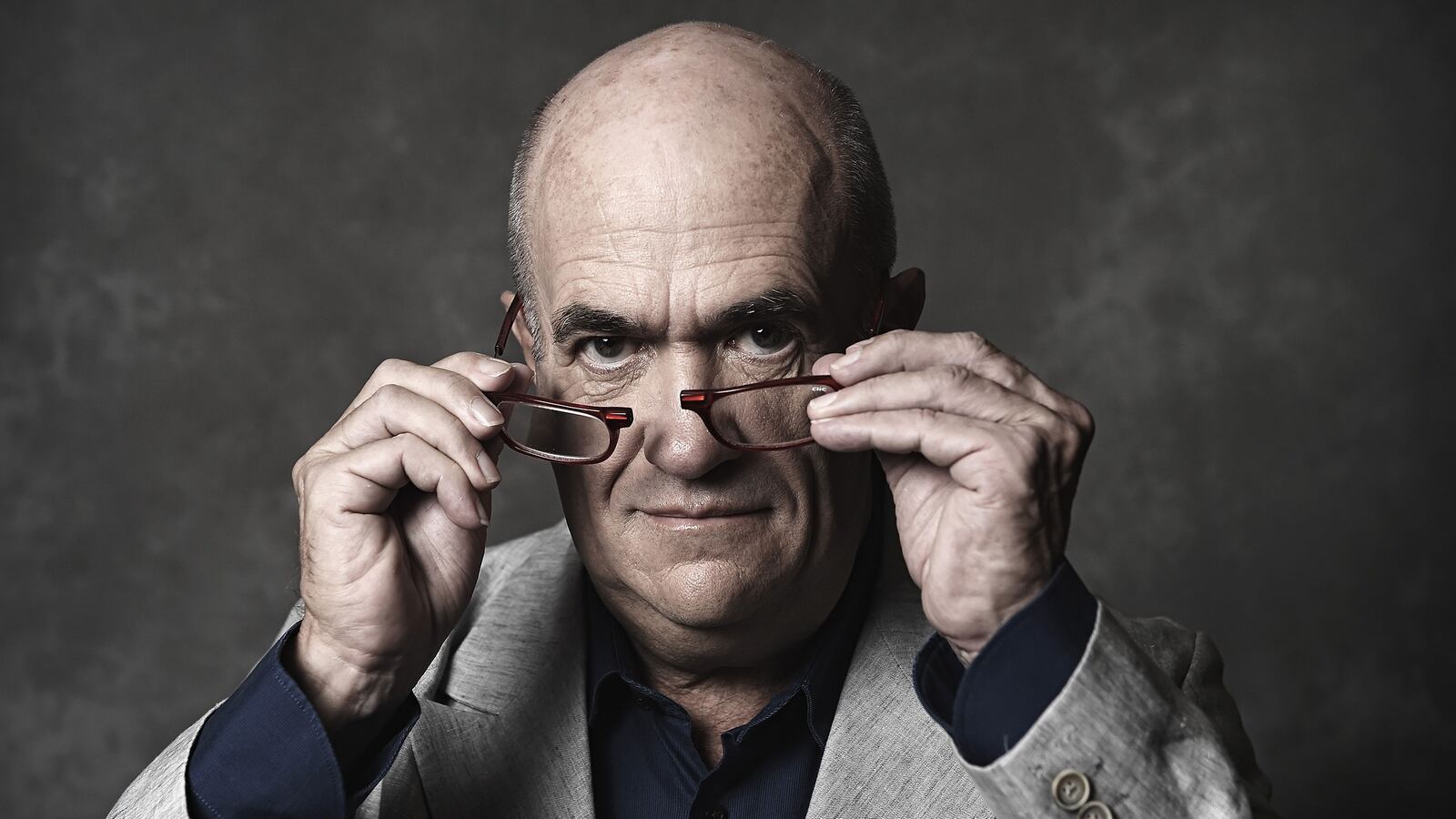

“Maybe I’m just doing it wrong,” sighs Colm Tóibín, the author of Brooklyn, The Master, Blackwater Lightship, and the fantastic new novel, House of Names.

I had asked Tóibín whether or not he held similar points of view to gay men of his generation (Rupert Everett being the most famous example) that young gay men today have given in, have traded the edginess that gay life once represented for heteronormativity and white picket fences.

“It’s a big argument if sexual difference makes you into someone who really should want to be effectively inventive in your life and do things that no one else has done,” he begins, leaning back as if to gather himself. “Or actually, if the hunger to couple, and the hunger to be with someone, and that stability of meeting someone and seeing the person you love waiting for you and look freely at that, isn’t a form of happiness that sure beats sitting up at a bar trying to look S&M—by S&M I mean the whole business of ‘I’m a stranger to you and I’m going to fucking eat you. I could do fucking anything to you, and that’s going to excite you’—down at the guy who just came in the door who’s your biggest fucking enemy.”

Tóibín shifts forward and confides, “Of course, the second thing is pure pleasure if it’s going to involve 25 good minutes of amazing sex in the dark with somebody who turns out all along to be working for the State Department or the CIA or the cops or is a priest or knows your cousin or pretends he’s Italian.”

For somebody who fills his books with silence, Tóibín in person is what one could comfortably call chatty.

Blotches of ink, honest to God, stain the 61-year-old writer’s hand as he briskly works through what seems to be an unending pile of editions of his latest novel in a back room of Washington, D.C.’s Politics & Prose bookstore. Born and raised in Enniscorthy in southeast Ireland, Tóibín attended University College Dublin and before embarking on a career as a journalist in the 1980s, which he documented in The Trial of the Generals. Beginning in the 1990s, Tóibín gained nearly universal acclaim for his fiction, going on to be shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize three times (Blackwater Lightship, The Master, and Testament of Mary). While still maintaining homes in Dublin and Enniscorthy, home for Tóibín is now New York City, where he teaches at Columbia University.

Peering over his red CliC reading glasses with his startlingly blue eyes, Tóibín kicks off the interview by making fun of me (“Oh my God, you’ve written out all of these questions”) and then trying to ease my apparent angst by swiftly following up with, “Let’s just have a little chit-chat.”

For the next three hours, we do just that, chatting about his new novel, how the Greeks did everything best, the outsize influence of Irish writers, modern gay culture, and our shared love of the painter Jack Yeats.

“The problem I have with that is simple,” Tóibín whispers when I tell him that parts of his new book reminded a friend of mine of Game of Thrones. “I didn’t know what Game of Thrones was until recently because somebody said to me what you just said, and I said ‘What’s Game of Thrones?’ I mean, I knew it was something on TV, like Mad Men or one of those things. But I’d never seen it.”

Tóibín’s new book, House of Names, tells his own twist of the tale of King Agamemnon (the leader of the Greeks in the Trojan War), his daughter Iphigenia (who is sacrificed by her father so that Greek ships may get favorable winds), his wife, Clytemnestra (who murders Agamemnon in revenge), his son Orestes (who kills his mother, Clytemnestra), and his other daughter, Electra (who eggs Orestes on). It is a tale whose dramatic origins are found in works by two of the greatest Greek dramatists: Aeschlyus’ Oresteia and Euripedes’ Iphigenia in Aulis. Tóibín’s version is a seamless blend of immaculately constructed, rip-roaring political turmoil and meditation on the high-stakes game of coming of age.

The comparisons between sections of Tóibín’s book with Game of Thrones reminded me of an interview with American Gods author Neil Gaiman in which he declared the idea that fantasy had now become mainstream as “bullshit” because, as he rightly pointed out, “The best-selling book ever is the Bible, which has all sorts of things. People coming back from the dead. Miracles. Magical things happening.” And so too with House of Names, in which Tóibín calls bullshit on the idea that George R.R. Martin and a lot of modern fantasy is revolutionary—as the Greeks were overflowing with gruesome regicide, gratuitous rape (sometimes even by animals—so take that, HBO!), torture, and twisted plotting.

“I remember once on National Public Radio,” Tóibín explains, “hearing the guy who wrote The Wire, and they said, ‘You obviously used quite a lot of Shakespeare.’ And he responded, ‘Oh no, it was the Greeks we went to for The Wire.’”

Unfortunately for HBO, but fortunately for me, Tóibín’s knives for paid cable drama were already out.

“And I remember lying in bed,” he continues, “and thinking what a very funny thing to say about The Wire, because I had tried to watch some of it but it was just people wandering on the streets. I’m just too old. I just couldn’t understand anything anyone was saying.”

Tóibín’s new novel is broken roughly into three parts. The first and the third parts are filled with the action: Clytemnestra’s plotting and then the staging of the murder of Agamemnon and then Electra’s plotting and success in having Orestes murder their mother. Without reducing Tóibín to his sexuality, as a gay man myself it’s hard not to see the glee with which he must have written the scenes of Clytemnestra. She might as well have operated with a playlist of the greatest revenge songs (“Hit ’Em Up Style,” “Bust Your Windows,” “You Oughta Know,” “Sorry,” etc.) on full blast. Her malevolent plotting against her husband spurs the plot forward at all times, even when she is offstage.

“The later Clytemnestra monologue came in a day,” Tóibín says, grinning as he recalls what it was like to write her character. “Because describing the whole thing in a tone I’ve set, it was sort of like finding a key, and once the voice was there I could let her go. The quality of her rage could make its way into the sentences.”

Her lover and co-conspirator, Aegisthus, is also given a new treatment by Tóibín. He spins him into this prowling Id-made-manifest, screwing everything that moves in a way that calls to mind the quote by the great womanizer Phillipe d’Orléans (recounted by none other than his own mother, and later used by Ben Franklin), who when confronted about his lack of discernment regarding the beauty of his conquests, replied, “Bah, Maman, at night all cats are gray.”

The final third of the book details the downfall of Clytemnestra as wrought by her second daughter, Electra, who manipulates Orestes into killing his own mother. The plot here is enriched by something Tóibín is best at writing about—secrets.

“The best novels are filled with a secret, which if told will be explosive,” Tóibín explains. “All the things people don’t tell people. Electra thinks her mother is almost responsible [for her sister’s death]. It’s never clear to her what her mother went through. Clytemnestra returns home to run things, to get things ready, but not to tell her daughter how she failed so badly… Because she doesn’t tell her that, her daughter develops this hatred for her.”

Sandwiched between these bookends of regicide, conspiracies, and naughty servant boys is one of the year’s most touching and heart-breaking love stories. It is touching because it is a depiction of an adolescent love that was pure and sheltered, and sure to stir memories in anybody who has experienced (or, frankly, always wanted to experience) such a time. And heart-breaking because it turns out to be one-sided and not meant to last. In this version, Orestes is kidnapped by Aegisthus in a power play and sent off to caverns with other boy hostages. He subsequently escapes with two of them (Mitros and Leander) to a secluded house where they all live with an old woman for half a decade. In that time, Orestes develops a particularly close bond to Leander.

“I wanted some image of the possibility of happiness to be there in the book,” Tóibín confesses. “So the relentless dark cruelty—so you could see there was a haven once. And also there is also that homoerotic thing that is so gentle between them, that is so natural. But means nothing to Leander.”

After a pause, Tóibín begins to grin as he explains his inspiration for much of the Orestes section, particularly when Orestes and Leander journey through a rough landscape to make it back home.

“In the time I was writing the Leander and Orestes stuff, I was living in L.A. with my boyfriend. We would go quite a lot, maybe once in a fortnight, to these hot springs in the desert, a really hidden place. I don’t even know what it’s called. You have to drive for two hours and then you have to walk for an hour,” he confides. “But the strange part is, you have to walk back but it seems much harder. He always knew the way, and of course I didn’t. So all of that second walking section, of the walking home, is absolutely him and me. Absolutely him and me. And the landscape, and me not quite knowing what turn now or how much longer is it.”

Tóibín told his boyfriend he was going to be in the book, although “it’s not exactly that, but that idea of almost finding with him a haven away from every form of trouble in L.A. certainly made its way into the book.”

There was another man, however, who caught the Irishman’s eye and inspired him to expand the character of Orestes—a character Tóibín thought was never well explored.

“What was happening at the time was the trial of the Boston Marathon guy,” he recalls. “I was interested in the idea of him being seven years younger than the brother who planned it. That he was sort of led. The silence of him in the court. The hurt look of him. But then the evidence against him. That he had stood there in the crowd knowing all these people were going to be injured badly in just a few minutes. And I just began to follow that.”

Tóibín had Luchino Visconti’s 1969 film The Damned on his mind as he wrote about Orestes, who would go from the innocent love-struck boy on a farm to the weapon with which Electra would strike down her mother.

“There is a cellist [in The Damned], and he’s not taking part in any of this,” muses Tóibín. “But by the end he’s the one leading them, who’s closest to the Nazis. He’s moved from being this artist to the actual manager of the firm for the purposes of the war. I was absolutely thinking about fascism. About someone who is all emotion, who is all openness to anything, and could indeed become the bomber, could indeed become the zealot, he could become anything.”

He tried to think of a character in novels without any luck who has “that same mixture of passivity, innocence, and is also a lethal weapon sitting there waiting to be influenced or egged on.” Somebody who is not a psychopath or stupid, but because he lacks a strategy, “means that anybody then can press on him in many ways. He will find anyone to lead him.”

‘House of Names: A Novel Hardcover’ by Colm Toibin. Scribner. 288 p.

AmazonBefore sitting down with Tóibín, I had on more than one occasion searched Google Images, trying to imagine what the author would be like in person. Unfortunately, he is smiling in almost none of the photos, but in more than a few he is either staring down the photographer or looking as if he’d rather be anywhere else. Needless to say, I worked myself into a lather thinking he was going to be intolerably eminent.

He turned out to be anything but. He gets as excited talking about the class he teaches at Columbia University or being home in Ireland (“people get your jokes”) as he does breaking down the motivations of the Henry James he created in The Master. He sways back and forth, peering over those CliC glasses when he wants to emphasize something, speaking in what a friend from Tóibín’s hometown assures me is a Wexford accent with a little time in England mixed in.

I pose to Tóibín a query that has weighed on my mind ever since I went to the National Gallery in Dublin and saw more there about what famous Irish writers thought about the paintings than I did about the actual painters. Why does Ireland have such an impressive place in world literature relative to its size?

“The only way out of poverty in the 19th century was literacy,” Tóibín explains. “Everybody wanted to get their son a job indoors. Outdoor jobs had all sorts of associations of working for others in the fields, in the harvest, building roads for the British. Every mother wanted her son to learn to read and write. So reading and writing became sacred in even the smallest households.”

That emphasis continued right into the mid-20th century, he claims, admitting that “one of the reasons my mother married my father was he had been to university and she liked the idea of this.”

The second major reason for Irish literary success, he says, was the proximity to London.

“London is as important for Irish writers as it is for Scottish writers,” he says. “London publishers really wanted a new Irish novel—and they still do.”

The subject of the National Gallery in Dublin brings Tóibín and me to another discussion—the wonderful work of Jack Yeats.

“Oooooh yeah. He’s wonderful,” Tóibín coos as I relate to him how Yeats’ work hanging in the museum moved me.

“I did a piece for The Guardian website called My Hero: Jack Yeats,” he continues. “He’s a big discovery, isn’t he? He’s never had a great retrospective in either England or America. You know his relationship with Beckett and all that? Beckett really admired him. They were friends.”

***

In a tense scene in Tóibín’s The Master, the English writer Edmund Gosse upbraids Henry James for using their friend J.A. Symonds’ marriage in The Author of Beltraffio. I wonder if Tóibín has ever been similarly scolded.

“Recently, I put a teacher into Nora Webster and a story called ‘The Name of the Game,’” he tells me. “Something horrible is said about him in both. And his nephew came up to me at something and said, ‘Why did you hate my uncle so much?’ Because I put his real name. And I said, ‘Well I didn’t like him and he didn’t like me.’” But while Tóibín may, like James, find inspiration for his characters in people from various stages of his life, the characters are often shaped by somebody even more personal.

“It’s sort of closer than that in a way,” he claims. “You end up putting versions of yourself into it.”

In addition to novels and short stories, Tóibín has also published works of nonfiction. One of his more well-known is Love in a Dark Time: Gay Lives From Wilde to Almodóvar, which leads me to ask him what these seminal figures would make of gay life today, where in the West at least, they can for the most part marry their loved one, have sex legally, and hold hands in public.

“Oscar Wilde would have had many, many jokes on the subject,” he laughs. However, “I think the most fascinating there is Thom Gunn. He really did live in the closet for very good reasons. He came to America in 1954. He witnessed the thing. Then in his poems suddenly the ‘you’ becomes ‘he.’ That’s a major moment where you can see somebody in their own life moving from one to the other.”

Which brings us to the moment Tóibín shocks me.

“I remember someone talking about when gay sex, as they call it—God, gay sex—was decriminalized in Ireland: ‘Oh, have you noticed it’s not very fun anymore?’ And I sort of said, ‘Was it ever that fun? When guys used to hang around that toilet on the quays. Are you sure that was really fun? Are you sure we really enjoyed all that?’”

“It seems there are a lot of gay men who want to move to the suburbs, get a mortgage, have a baby or two babies and be really domestically happy using what people might call a heterosexual model,” he continues. “And since that’s the case, we really have to take people at their word as to what they want. Am I going to start telling people that this is somehow giving in?

He admits that “that sort of modern happiness may not lend itself to the easy drama you could get before from the anonymous gay sex, the street, the bathroom, the locker room, all those places.” But while “people got immense buzz from anonymous sex,” it “actually created a great unhappiness, misery, and tragedy.”

I point out that he isn’t exactly known for being so graphic sexually. That, in fact, he’s better known for the sort of homoerotic missed chances that fill The Master and power the middle section of House of Names.

“When it came to The Master, the almost-ness could have much more power than the act,” he cautions. “Someone did say to me, why are you describing the violence in such graphic detail and not the sex? I felt being coy was being better. You could feel [in House of Names] Orestes’ need for Leander when they would be down on a rock and Leander would come down and hold him. But if you went into it in physical detail you could lose it, it would lose its power.”

But for those who don’t think he writes graphic sex scenes, Tóibín suggests picking up his short story The Pearlfishers, in which there is a very explicit sex scene with a memorable simile involving jam, even though the author harrumphs that he “hates similes.”

A knock on the door disturbs our session—the store is closing shortly. Tóibín has some things he wants to buy, including a travel guidebook for Rome. I expected him to meander up and down the aisles, but that night, at least, he walks with purpose—and fast. After the trek through a variety of guides, he makes a beeline for the magazine section.

“Do you see The Economist?” he asks. It’s supposedly running a review of his book, and if it’s bad, he’ll want me to read it because, he says, “nobody enjoys a bad review.”

Reconvened in the lobby of his hotel after snaking our way through northwest D.C. traffic, I ask Tóibín what I often ask writers: What does he hope people will think about when they finish the book?

“There’s a poem by Geoffrey Hill, called Ovid in the Third Reich,” he begins. “The opening lines are,

I love my work and my children. God

Is distant, difficult. Things happen.

Too near the ancient troughs of blood

Innocence is no earthly weapon.”

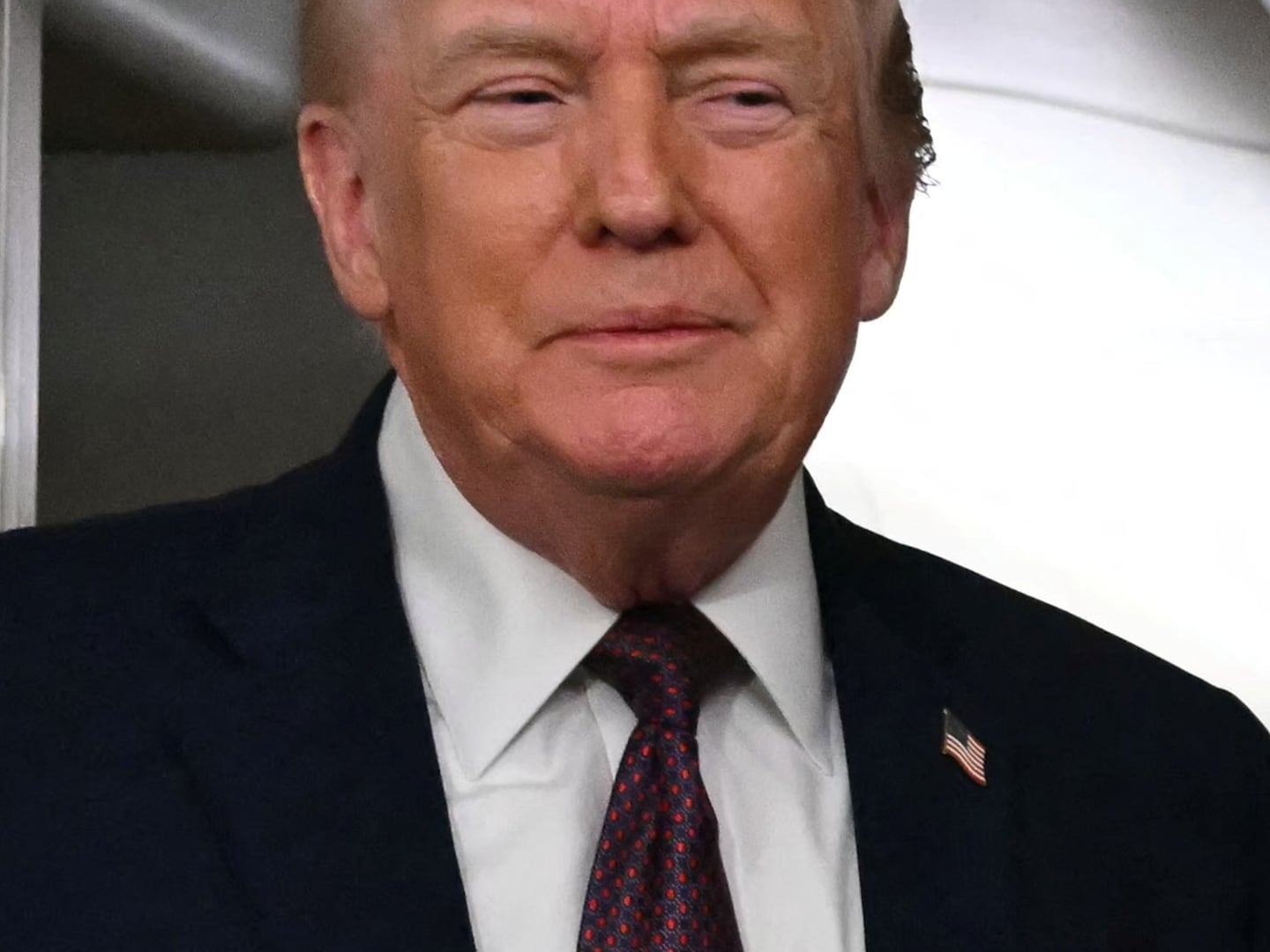

For Tóibín, “weakness is really something we need to know about.” Fresh on the author’s mind is something that just happened in the news. “I saw the other day with the deputy attorney general, Rod Rosenstein, there’s something he clearly should do. I mean he was clearly set up, and he really had to take some action. We’re constantly living with events where somebody should do something and we can watch them deciding not to do it.”

So for Agamemnon, clearly he should have put a stop to the sacrifice of his daughter. “In the case of Clytemnestra, it’s that once she begins, she cannot stop. She will commit the most appalling atrocities,” he explains. But, “the one that matters most is Orestes. What I wanted to suggest is that in us all is Orestes.”

“If any of us talk about how we’re good people, or that under pressure we’d know exactly what to do, I’m not sure about that. And we all need to know that,” he says firmly. “All I’m trying to do is dramatize the gap between what we think we are and what we might become under certain pressures.”