CALI, Colombia—The video shows two cops kneeling on a lone man in the street. He’s prone and helpless, yet the officers continue to exert deadly force. As the man calls out that he can’t breathe, onlookers plead for mercy. Later the man is pronounced dead, the video goes viral, and anti-police protests begin to sweep the country.

Sound familiar? While the scene bears an eerie resemblance to the killing of George Floyd, the victim in this case was Bogota-based engineer and law student Javier Ordóñez. He was killed in the early hours of Sept. 9, allegedly for not following COVID-19 social distancing restrictions.

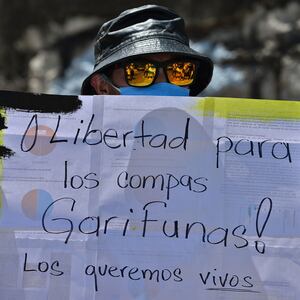

Large-scale demonstrations against police brutality began the next day in Bogotá and soon spread to Medellín, Cali, Popayán, and other major cities. The protests have been compared to the Black Lives Matter and “Defund the Police” movements in the U.S. However Colombian authorities reacted to these marches with a brand of ferocity seldom seen stateside, repeatedly using live rounds and firing indiscriminately into crowds of unarmed civilians, and thus further fanning the flames of unrest.

“The police are systematically repressing us. They’re depriving us of the fundamental right to peaceful protests,” Alejandro Lanz, co-director for the human rights NGO Temblores, told The Daily Beast. “They are escalating the violence without regard to human life.”

Since then at least 13 protesters have been killed and 209 wounded. Multiple women also came forward to say they were sexually abused by officers after being detained. The crackdown was swiftly condemned by groups like Amnesty International and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and prompted charges of “state terrorism” from several media outlets in the country.

In one telling incident, an underage protester died after being shot four times at close range, despite police claiming he was hit by “stray rounds.” In another episode, three young female protesters were arrested and taken to a precinct bunker miles away from the demonstration site in Bogota. There the women said they were groped by officers who offered to “overturn” their arrest in return for sexual favors. The women eventually escaped when the precinct commander returned to the base and ordered them released.

As they came under fire the protests turned violent, eventually leading to 194 officers injured and dozens of police stations being set on fire. Such intense resistance prompted the former Colombian president and current senator, Álvaro Uribe, to call for “a national government curfew, armed forces in the streets with their vehicles and tanks, deportation of foreign vandals, and capture of intellectual authors.”

For their part, demonstrators said they’d been left with little recourse to get their message across.

“This is all happening because of oppression,” said Astrid Olaya, an activist and grade-school teacher in Cali, during an interview with The Daily Beast. “The people are only raising their voices, but unfortunately, in order to be heard, they must resort to vandalism. That’s sad but it’s also reality.”

Gimena Sanchez-Garzoli, a Colombian expert with the Washington Office on Latin America [WOLA], said the public’s “grievances are legitimate” while also calling authorities’ response a “disproportionate use of force [for] lethal or maiming purposes.”

“[Police] actions being caught on video and circulating all over just makes the anger grow,” she said.

“I Can’t Breathe.”

All that roiling anger brings us back to the original video, which shows the killing of law student Ordóñez while in police custody, and which first spurred national outrage.

According to witnesses, Ordóñez, 46, was accosted by a squad of officers just after midnight in the middle-class Villa Luz neighborhood in northwestern Bogotá. Police later claimed the father of two was in violation of coronavirus restrictions punishable by fine. However, witnesses also report the arresting officers appeared to know and verbally identify the victim, indicating he may have been deliberately targeted, according to a report by the North American Congress on Latin America [NACLA].

“Before the police knocked him to the ground, [Ordóñez] appealed to his right to appear before the appropriate authorities if he had committed any illegal act. But the police simply held him down and began to shock him,” NACLA reported.

In the video shot by an onlooker, Ordóñez can be heard to say, “Por favor, no mas, me ahogo.” [Please, no more, I can’t breathe.] An autopsy revealed that Ordóñez had been Tasered more than a dozen times, also suffering blunt-force blows that left him with cranial fractures and a ruptured liver.

Unfortunately, Ordóñez is only the latest in a long line of victims of police and military violence against civilians in Colombia. According to the U.N. Human Rights Commission, there were 15 extrajudicial killings by the country’s security forces last year. Other sources, including a recent op-ed in The Washington Post, put the number much higher—claiming there have been as many as 639 homicides and almost 250 sexual assaults by police and soldiers since 2017.

Two days after Ordóñez’s murder, Defense Minister Holmes Trujillo offered a mea culpa of sorts, stating that “the National Police apologizes for any violation of the law or ignorance of the regulations [that] may have been incurred.”

By that point, however, the video of Ordóñez’s gruesome death had been viewed by hundreds of thousands of people all over the world and the anti-protest crackdown was ongoing.

Sergio Guzmán, the director of Colombia Risk Analysis, called Trujillo’s apology “too little, too late” in an interview.

“There will be no attempts made at big changes [to police conduct] in the near future,” as any such plans for reform would be “dead at birth,” Guzmán said. “So that's where the apology problem is unfortunately magnified.”

Colombia’s current president, Iván Duque, is a far-right Trump acolyte who campaigned on a strict law-and-order, pro-business platform. Duque has also shied away from reconciliation talks or meeting with victims’ families.

“Duque and his ministers have not shown much empathy nor interest in victims of violence nor in changing the way the police operate against the general populace,” said WOLA’s Sanchez-Garzoli, who also accused Duque of pursuing policies aimed at rolling back human rights.

“Among the rollbacks we’ve seen is efforts to restrict social protests,” she said.

“The Cops Can Kill Us As They Please.”

Despite a 2016 peace agreement meant to end its long-running civil war, Colombia has been caught up in a wave of violence during Duque’s first two years in office. That includes a string of mysterious massacres, as well as assassinations of leftist social leaders and activists. The country has also been hard hit by the pandemic, with per capita cases of COVID hovering among the highest in the world and leading to stark increases in unemployment and poverty.

All of that made for something of a perfect storm when news of Ordóñez’s killing broke.

“Colombians have been glued to social media, TV and radio, hearing about the protests concerning police brutality in the U.S. So when the video of Javier Ordóñez surfaced it just detonated all of these underlying frustrations and anger that had built up,” said WOLA’s Sanchez-Garzoli.

Human rights director Lanz said there is a common ground underlying both nations’ anti-police movements—in that both are triggered by creeping authoritarian tendencies and enabled by the sharing capacity of social media.

“We need to think globally about how we can change this notion of the police force in public space,” Lanz said. “The police in all countries, not only in the United States and Latin America, tend to criminalize black people, young people, and LGBTQ people, and that directly impacts our freedoms and the right to engage in social movements.”

But there are intrinsic differences between BLM and what is happening in Colombia, said security analyst Guzmán.

“In the U.S. the problem relates to white supremacy,” he said, whereas in Colombia the issue is more one of “impunity” for police officers. Instead of being tied to race, Guzmán described it “more as a cultural problem from within the police, the way the police work, the way they aren’t held accountable” for their actions.

“This should be changed,” he said, “but there is no favorable political environment for that.”

Activist Olaya agreed that the problem in her country was more about abuse of power for political and economic ends, as opposed to racial prejudice.

“In some ways I think our movement is very similar to what is happening in the U.S. [...] but a difference is that the police attack and intimidate us to protect the power of the elites and the oligarchs. There is no question we live in a dictatorship, and the [the cops] can kill us as they please without any implications.”

Some scholars have argued persuasively that the problems of racial injustice in the U.S. are also tied to questions like class inequality and neoliberal agendas. But what does seem to separate the two countries’ police reform movements is a matter of scale. While some high-profile cases, like those of Breonna Taylor and Tamir Rice, tragically remain unresolved in the U.S.—in Colombia unsolved murders by security forces are the norm. Low wages and a lack of training mean that crooked cops are an endemic problem, and the nation's police force remains one of the most unethical in the hemisphere.

“Colombia still has weak political capacity compared to the U.S.—the rule of law is far less ingrained in police forces [and] issues of corruption are also more of a concern,” said Robert Bunker, a research director with the U.S. security firm C/O Futures.

“In Colombia a police officer is expected to literally get away with murder,” Bunker said. “In the U.S. they are expected to be punished for such a heinous act.”