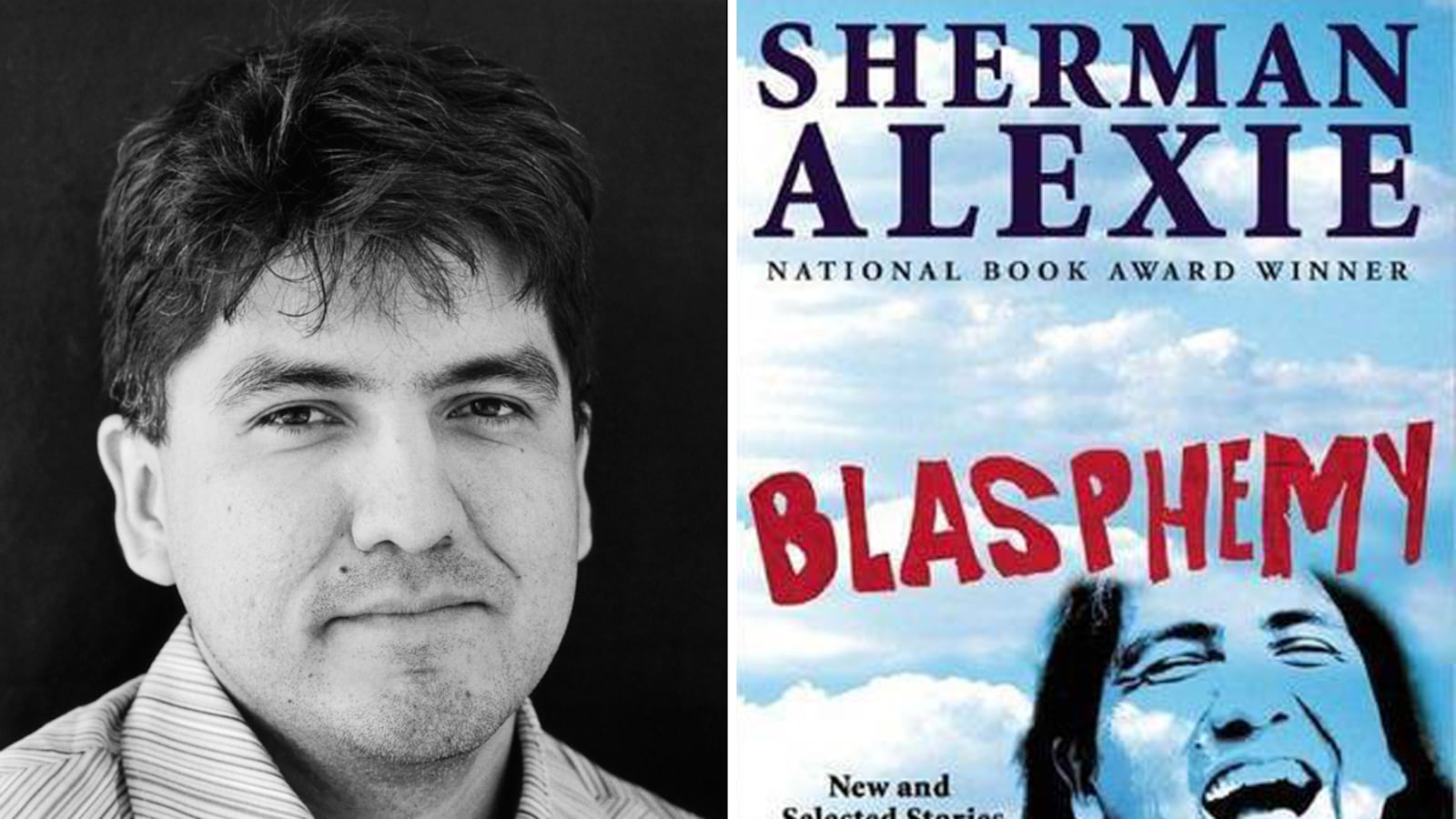

Sherman Alexie is a poet, a PEN/Bernard Malamud-award winning short story writer, a novelist, a screenwriter, a director, a stand-up comic, winner of a National Book Award for his YA novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, and an enrolled Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Indian.

In 1992 when Alexie published his first book, The Business of Fancydancing, with Brooklyn-based Hanging Loose Press, he was brash (“When I first started writing, it was mostly about unfocused rage at the toxic racism in the USA,” as he puts it). Now, at the age of 46, he has been mellowed by an all-access pass to literary America, winning most of the prizes around. Fathering two sons, now teenagers, has humbled him. He has honed the blade of his wit (called “razor-sharp” in multiple reviews and citations) to a fine polish and also embraced the digital world (“I am always hungry. My Indian name is Binges With Wolves,” he told his 26K Twitter followers the other day).

Blasphemy: New and Collected Stories draws from two decades of work, including stories from The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven and War Dances (PEN Faulkner award) and fifteen new stories, which he revised extensively—“dozens of drafts,” he said.

I first interviewed Alexie just before Smoke Signals, the film he wrote and coproduced, was released. Last month we continued our years-long on and off dialogue.

Why call the new collection Blasphemy? (I was struck by your use of the word in your story “Cry Cry Cry:” “He reduced Jeri all the way down to the sacred parts of her anatomy. And those parts stop being sacred when you talk blasphemy about them.”)

I called the book Blasphemy primarily because I’ve been so regularly accused of being blasphemous by white folks and Indians. But they only speak of blasphemy in its most basic terms: disrespect toward religion, toward a philosophy. I think blasphemy is actually more directed toward other human beings, and most often expressed toward those who have lesser power in society. I think human beings are sacred and that all the evil shit each of us does is blasphemous…. White folks talk about finding the sacred in the wilderness, and I suppose it’s there, but I hear the sacred in 3 a.m. traffic and 747s descending and loud music from the house down the block and the ship horns in the foggy night and the whirr, whirr, whirr of crowds. If people are sacred then the most sacred places are the ones where the most people have gathered.

Is there anything you’d like to say about meth that you didn’t say in “Cry Cry Cry?” How do you think the meth epidemic will resolve?

Meth will be replaced by a newer, cheaper, more effective drug. And drug addiction won’t diminish without more economic and racial equality. Yes, drug addiction in US society is directly proportion to economic inequality.

By now you are, I assume, used to being called an “Indian superstar.” What keeps you grounded?

Hey, I get called a “superstar,” as well as an “Indian superstar.” I get the adjective-free praise, as well! What keeps me grounded? I didn’t marry a fan. My sons aren’t interested in coming to my performances. My friends aren’t big fans, either. I haven’t made groups of friends based on our mutual writing careers. Most of my friendships center on basketball. So I guess you could say I stay centered in the midst of fame because I avoid people who care about my literary fame. I have ended newish friendships and professional relationships when I’ve discovered that my fame is a part of the attraction. What’s the best antidote for fame? The loving contempt of your friends and family.

Your newer stories are not as long as the earlier stories that first appeared in The New Yorker, like “What You Pawn I Will Redeem.” Some reflect your talent for the one-liner, like “The Human Comedy,” a six-word story you published in Narrative magazine. Is there a reason you now favor briefer stories?

Though I have a reputation for being a Luddite, I actually love the new digital technology and its artistic possibilities. So I have certainly been writing very short stories because they look great on my iPad screen! It’s a callback to my early days of writing. I began my career on a manual typewriter and found that the physical act of pulling a sheet from the typewriter dictated the end of a poem. So I mostly wrote very short poems as a result. But when I moved to a word processor, my poems grew in length. And then I began to write stories and the beginnings of novels. The shape of the machine influences the shape of my work.

What are the top five surprising things Americans don’t know about Indians?

- Approximately 70% of Indians live in urban areas. The reservation experience is actually the minority experience in the Indian world.

- The political divide between rural and urban Indians mirrors the urban/rural political divide in white America. Reservation Indians tend to be pro-gun, pro-life, pro-prayer in schools, pro-war, and anti-gay. I’m amused when liberal white folks go all ga-ga over rez Indians.

- Though the males of the American Indian Movement (Russell Means, John Trudell, Dennis Banks, the Belacourt brothers) have received most of the fame, money, and attention, it’s the women of the American Indian Movement who created the most long-lasting legacy: schools and the commitment to higher education.

- Indians join the military in epic numbers. 85,000 Indians served in Vietnam and 90% of them volunteered. Indians are ironically patriotic. My joke: Yeah, we Indians can insult the USA all we want, but if white guys do it, we’re going to punch you in the face. “Don’t talk shit about my country. I’m the only one who gets to talk shit about my country.”

- Indians are almost universally funny. My sense of humor might make me stand out among other literary writers but it makes me part of the mainstream in the Indian world.

Speaking of funny, to what extent do you define yourself as a stand-up comic?

I’m not always sure what to call myself. I think “writer” generally covers it, though “storyteller” sure does sound more indigenous, huh? There’s still a slight bias toward multi-genre writers, I think. And I think the literary world considers it more rare than it actually is. As I began my writing life, I was reading mostly other Native writers [James Welch, Simon Ortiz, Leslie Marmon Silko, Joy Harjo, and Adrian Louis] and they were all multi-genre folks writing poetry, short stories, novels, screenplays, stageplays, and were often musicians, painters, sculptors, and actors, as well. If you walked into any reservation school in this country, into a fourth grade class, and asked the Indian kids how many were actively and daily engaged in an art form, I’d guess that at least 90% of them would say yes. Artistic expression is rather ordinary in the Indian world. Though I’m a writer in the Western Civ sense, I’m also very much a product of my artistic tribal background. Simply put, I’ve been funny since birth. And so have my brothers and sisters. I’m not so much a stand-up comic as I am a guy who had to keep up with his verbose family at the dinner table.