By Rachel Bluth and Emily Kopp

When a small Australian biotechnology company, Innate Immunotherapeutics, needed a clinical trial for an experimental drug it hoped to turn into a huge moneymaker, the company landed a U.S. partner where it had high-level connections: Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y.

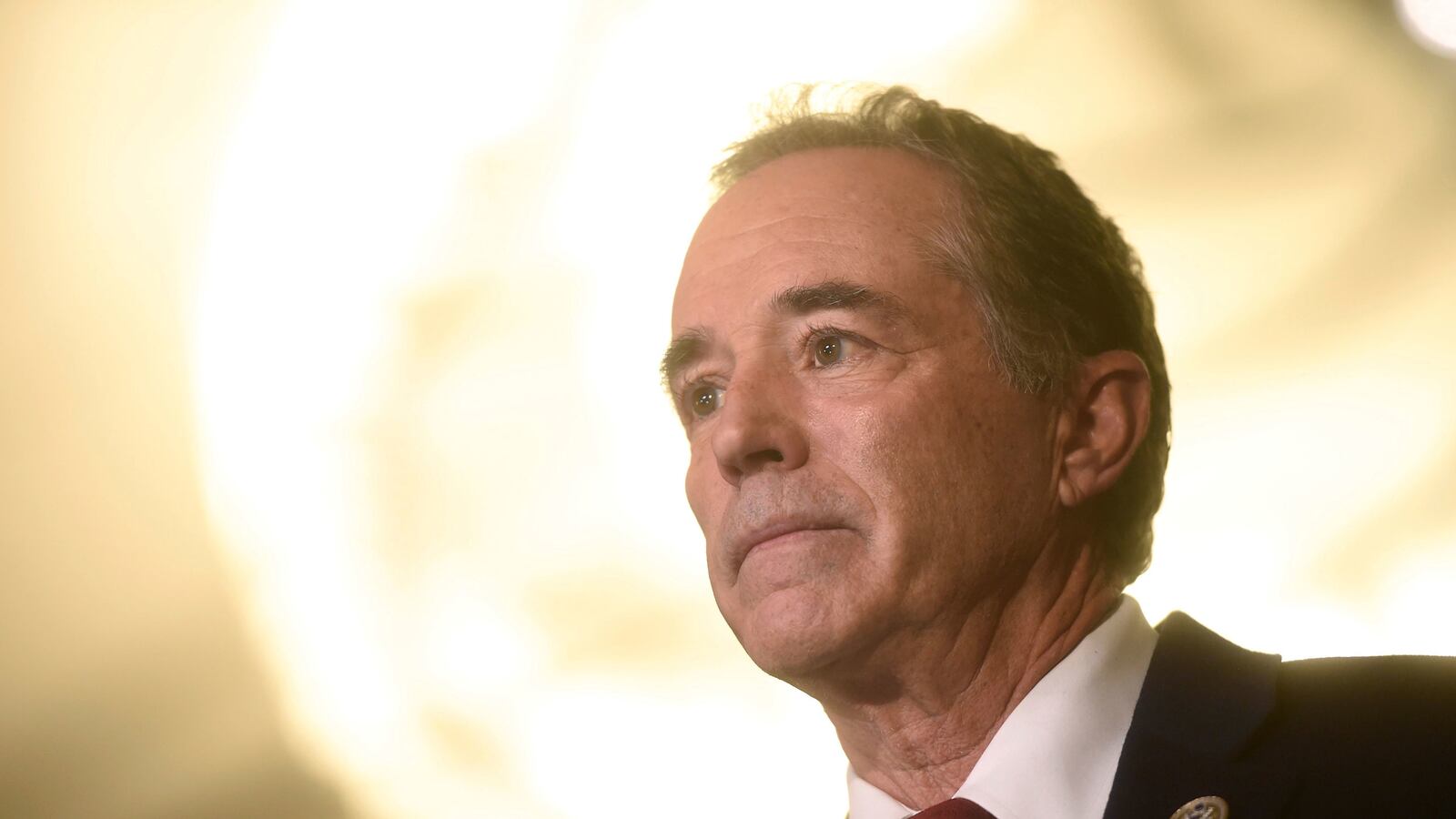

The company is partly owned by Rep. Chris Collins, a wealthy Republican entrepreneur from Buffalo, whose enthusiasm for Innate helped persuade others to invest. Former Rep. Tom Price, now secretary of Health and Human Services, bought Innate stock after Collins told him about it, Price said at his Senate confirmation hearing. Other shareholders include Collins’ campaign supporters, some of whom are key figures in Buffalo’s medical corridor, company and government documents reveal.

Federal money is in play, too: National Cancer Institute funds are being used to test an application for Innate’s drug that could make the company more attractive to potential buyers. Innate has said in presentations to investors that it hopes to sell itself to a major pharma company by the end of 2017.

The Roswell clinical trial, which could start this month, will investigate whether MIS416 might have an application as an ingredient in a vaccine for ovarian cancer. Innate’s primary strategy, however, is to develop the drug for advanced multiple sclerosis and it has told investors that the results of early-stage human trials in Australia and New Zealand against MS will be reported by this fall.

With its tangled web of medicine, politics and money, Innate’s story has proven irresistible for U.S. news media, whose initial reports in December that Price received discounts on Innate stock purchases helped place the secretary on the hot seat as he won confirmation. Now, the story is exploding half a world away, and the focus is shifting to Collins. The Australian newspaper’s website reported Feb. 6 that a former securities regulator there alleged Collins may have violated disclosure requirements in the country’s securities laws in acquiring his Innate stake and also by not reporting his close relationships with other large shareholders. The Australian government’s Takeovers Panel said Feb. 15 that it has not decided whether to convene a panel to investigate the allegations.

Innate CEO Simon Wilkinson said in a statement that company financial documents “fully informed” financial markets about Collins’ investments. The company was “not in the slightest bit concerned” about the allegations, which “are politically motivated and have been peddled by hack journalism,” he said.

Compared with Price, the potential conflicts could run even deeper for Collins who—along with two children—owns more than 21 percent of Innate’s shares. He is its largest shareholder, company reports show.

Collins, who is ranked by the Center for Responsive Politics as the 14th-wealthiest member of Congress, sits on the health subcommittee of the Energy and Commerce Committee, where he helps oversee health care funding. He was a member of President Donald Trump’s transition team and is a liaison between the new administration and Capitol Hill.

Congressional ethics rules do not prohibit Collins and other members from investing in companies whose businesses overlap with the committees they serve on and the government agencies those committees oversee, legal experts said. Even so, they added, members must take care to disclose possible conflicts of interest because they can erode the public’s trust in government.

“Members should not have large holdings in health care stocks while serving on committees that oversee health policy,” said Richard Painter, former chief ethics lawyer for President George W. Bush.

Collins’ spokesman said his boss has done nothing improper.

“Congressman Collins is not going to apologize because a company he has a relationship with is attempting to help conquer cancer,” said Collins communications director Michael McAdams. “It’s sad the media is attempting to launch partisan attacks insinuating otherwise.”

‘I Talk About It All The Time’

Collins has been candid about his promotional efforts on Innate’s behalf.

In an interview with CNN, Collins said he often talks to people about Innate. “I talk about it all the time, just as you would talk about your children,” he said.

Last month, Collins was overheard by reporters boasting on a cellphone call just off the House floor about the “many millionaires” he had made talking up Innate, according to Politico.

Innate’s drug is an immune response stimulator discovered in the 1990s that had initially been developed as a potential treatment for HIV/AIDS or to boost the efficacy of childhood vaccines.

Founded in 2000, the company later tried MIS416 in a number of medical uses, but never found a marketable niche, Innate’s financial reports and news reports show.

Collins’ ties to Innate go back to 2005—seven years before he was first elected to Congress—when the successful Buffalo businessman decided to invest after meeting Wilkinson while the CEO was in the U.S. seeking investors, Wilkinson said.

Collins joined the board in 2006 and the company first sold shares to the public in 2013. From 2013 to 2016, he bought Innate shares then worth between $3.5 million and $16 million and has not sold any, according to his congressional disclosure statements. Collins now owns nearly 38 million shares of the company, worth about $25 million based on the stock’s recent closing prices on the Australian stock exchange. That price peaked at $1.35 a share on Jan. 25 and is now under $1.

Innate has never had a revenue-producing product and has relied mainly on investor capital for funds. The congressman made four personal loans to Innate in 2012 and 2013 totaling $1.3 million that were later converted to shares and options to buy more shares at discounted prices, according to company financial reports.

Collins also promoted Innate among people in his professional and social circles, drawing investors whose share purchases have helped keep the company afloat.

Americans own 44 percent of Innate, according to a company-funded research report on its website. Many of those shareholders seem to come from an interconnected circle of prominent Buffalo investors with Collins at the center, based on company documents, congressional disclosure statements and political contributions reported in Federal Election Commission filings.

Investors who bought stock in two private placements by Innate have contributed at least $105,000 to Collins’ congressional campaigns, according to the Public Accountability Initiative in Buffalo, a nonprofit that investigates politics and government, which compared an Innate shareholders’ document with FEC filings.

One was Glenn Arthurs, an executive in the Buffalo office of UBS, the Swiss financial services giant. Another was Paul Harder, who runs a private investment firm in Buffalo, CHEP II. Arthurs and CHEP II both ranked among Innate’s top 20 shareholders last year, according to the company’s annual report. Both have also contributed to Collins since 1998, the year of his first—and unsuccessful—congressional campaign, FEC records show.

Collins’ congressional chief of staff, Michael Hook, who began working for Collins early last year, bought shares of Innate 28 times last year, according to his disclosure statements. Sometimes he purchased thousands of dollars of stock multiple times in a single day, those filings show.

Bill Paxon, a former congressman from Buffalo and a lobbyist whose clients include PhRMA, the major drug makers’ trade group, has invested in Innate. So has Lindy Ruff, the former coach of the Buffalo Sabres hockey team, who is now head coach of the Dallas Stars. Both were identified in a public company document for shareholders.

Ruff declined to comment on his Innate investment. Paxon, Arthurs, Harder and Hook did not reply to repeated requests from KHN for comment.

Mark Lema, Roswell’s head of anesthesiology, told The Buffalo News recently that he became an Innate investor after overhearing Collins discussing it at a meeting for Buffalo visitors that Collins hosted in Washington, D.C. But he’s never discussed Innate or MIS416 with study researchers at Roswell, he said in a subsequent interview with KHN.

A Complaint In Australia

Recent published reports in the U.S. detailing Collins’ ties with Innate are what provoked Sydney lawyer—and Innate shareholder—James Wheeldon to question Collins’ adherence to Australian securities laws, according to the 10-page letter that he sent Feb. 3 to Innate and the Australian Securities and Investment Commission.

Wheeldon alleged that Collins failed to disclose his large holdings in Innate to the Australian Securities Exchange within two business days of becoming a substantial stockholder, as the country’s law requires.

Stating that Collins owned more than 15 percent of the company before Innate went public in December 2013, Wheeldon alleged that Collins did not inform the exchange how much he owned until almost 18 months later.

Wheeldon also said that published reports about Collins’ “family, professional, political and financial relationships” with other Innate shareholders like Price had never been disclosed to the Australian financial market to his knowledge, “but rather has only come to light as a consequence of these press reports.”

Collins, his children, political allies and his donors control at least 27.25 percent of the company—giving Collins greater influence over the company than has been disclosed to shareholders, Wheeldon wrote.

“Mr. Collins duty is not to enrich the business and political elite of Buffalo, New York. His overarching duty is to the company,” read Wheeldon’s letter.

The stakes may be high, but the data from the Roswell study might not produce strong conclusions. Twelve people will be in the study, which is to be completed in August 2018, according a listing on clinicaltrials.gov. The start of the trial has been postponed five times since July and is now scheduled for this month. Recruiting for participants has not started yet, according to the listing.

Innate and Roswell began collaborating in 2009 and as both sides tell the story, Collins—the man who first connected the Australian biotech firm to Buffalo—had nothing to do with it. According to Roswell, the doctor running the trial, Kunle Odunsi, learned about MIS416 that year when Wilkinson, the CEO, pitched the drug at a presentation in Buffalo to prospective collaborators. Roswell researchers have been testing the vaccine in mice with tumors since first receiving the National Cancer Institute grant in 2011.

The trial is called an “investigator-initiated” trial, meaning that Odunsi has an agreement with Innate to explore the use of MIS416 for a cancer vaccine for free. Innate donates the drug, Roswell sponsors for the trial and if it’s successful, researchers could approach a medical journal to publish the results.

“A publication by a reputable clinical center (e.g., Roswell) in a prestigious journal […] would almost certainly increase off-label usage, thus increasing sales,” Kenneth Kaitin, director of the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, wrote in an email.

Wilkinson said Collins has played no role in lining up the clinical trial at Roswell or getting the NCI funds to pay for it. McAdams, Collins’ spokesman, said Collins had “zero involvement” in the grant.

Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit health newsroom whose stories appear in news outlets nationwide, is an editorially independent part of the Kaiser Family Foundation.