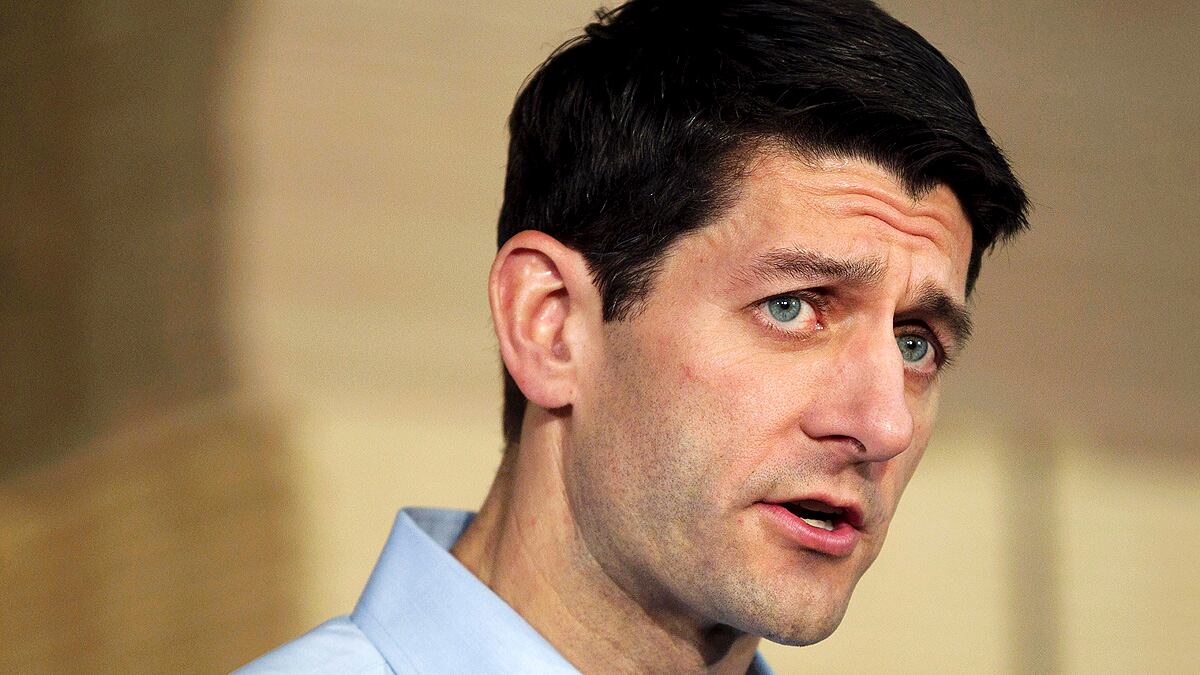

Mitt Romney can try to backtrack all he wants, but the moment he picked Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan as his running mate, he effectively adopted Ryan’s budget proposal as his own. This could prove to be a problem given how broadly unpopular its provisions are—that is, if most voters can even discern those provisions amidst the smoke and noise of a rapidly intensifying presidential campaign.

So what are the provisions? Ryan’s proposal, if enacted, would constitute a massive revamping—and shrinking—of certain key aspects of the social safety net. In addition to tossing out the Affordable Care Act, Ryan would replace Medicare with a voucher system that enrollees would use to buy private insurance or enroll in the traditional program—the end result, according to the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, would likely be less coverage.

The Ryan budget would also transform Medicaid from an open-ended federal commitment into a block-grant program, leading to even more drastic cuts there. On the tax side, the plan would both extend the George W. Bush tax cuts and grant further cuts to high-income taxpayers while slightly increasing taxes on the poorest. (Ryan’s plan doesn’t include any new sources of government revenue.)

Overall, then, the plan would radically reshape government, and cut out huge chunks of it in the process. Ryan’s justification for all this slashing is his belief that the federal budget deficit is an emergency that needs to be addressed immediately.

Do Americans agree? Carroll Doherty, editorial associate director at the Pew Research Center for People & the Press, told The Daily Beast that in the abstract, Americans are concerned with the deficit (although less concerned than they are with issues like the economy and unemployment), and they favor addressing it with a balanced approach of tax increases and spending cuts. But “when you get to the specifics of which taxes and which programs [to cut], there’s a lot more division,” he said.

And the entitlements targeted by the Ryan proposal are very politically popular. When Pew asked voters about the Medicare aspect of the Ryan proposal last year, it found what appears, at first glance, to be a relatively even split, with 41 percent opposing the policy and 36 percent approving. But a deeper dig suggests there is less support for the proposal than meets the eye. “This was not highly visible to the public at the time,” Doherty said, pointing out that just one in five Americans had heard “a lot” about the proposal back then. And among both independents and Democrats (but not Republicans), the more someone knew about Ryan’s proposal, the less likely he or she was to support it.

Polls asking not about the Ryan plan itself but about the specific policies contained within it, paint a similarly discouraging picture for Republicans.

As of last summer, twice as many respondents chose to keep their current entitlement benefit levels as chose to cut them to chip away at the deficit. There was a similar gap when they were asked whether people on Medicare already bear enough of their health costs—respondents answered with a resounding “Yes.”

These results brought with them a significant age divide. “What’s striking is the degree to which older Americans, 65-plus, are tuned into this debate, and then the degree to which they oppose changes in the program that would entail more costs on the beneficiaries,” said Doherty.

As for Medicaid, which one might think would garner less sympathy because it is often associated with poor and minority recipients (even though the elderly and the disabled often rely on it as well), respondents still overwhelmingly preferred keeping benefits where they are to letting states cut back.

When it comes to taxes and the deficit, voters consistently prefer a mix of tax increases and budget cuts to either one or the other, and a strong plurality think the rich should pay higher taxes.

In short, there’s a good case to be made that every major element of the Ryan budget is unpopular with voters.

If they knew what was in it, that is.

“I’m fairly skeptical of the idea that voters become highly informed” of what’s in the plan, said Paul Pierson, a political science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and coauthor of Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. “There’s just so much noise.”

Larry Bartels, a professor of political science at Vanderbilt University, agreed. “If they studied the proposal for half an hour between now and November, most of them would oppose it,” he wrote in an email. “Government spending is unpopular in the abstract, but mostly popular when it comes to concrete programs. But it is a mistake to assume that they are going to do that—or that their thinking about fiscal issues will follow any neat, logical pattern recognizable to policy wonks.”

Still, Democrats and their allies are already racing to fill this information gap by disseminating the details of the Ryan plan. So Romney faces a difficult balancing act. On the one hand, he wants to benefit both from the gravitas with which many on the right and in the press view Ryan, who is commonly portrayed as a wonky, numbers-obsessed budget geek, and from the signal the pick sends to affluent political players who are enamored of Ryan’s brand of wealth-friendly redistribution. On the other hand, he has to sidestep the nitty-gritty of Ryan’s budget proposal, since voters are likely to recoil when (or if) they are faced with the plan’s specifics.

This helps explain why the campaign’s strategy is to emphasize that Romney will be generating a plan of his own rather than simply adopting Ryan’s.

Pierson also pointed out that “one of the very first things [the Romney campaign] did in the last couple of days was talk about Obama’s $700 billion Medicare cut.” In other words, it’s a preemptive strike: before there’s any risk of voters becoming informed of the Medicare cuts in the Ryan plan, plant or reinforce in their minds the idea that it’s actually Obama who is trying to cut Medicare (this oft-repeated claim, it should be pointed out, is false).

So, stepping back, what does it tell us that Romney chose as his running mate a man whose name is synonymous with a plan likely to be quite unpopular among the very independent voters presidential candidates are supposed to target?

“It tells you something about the party and where strength lies in the party—and it lies at the conservative end,” Pierson said. “It really lies at the conservative end.”

Jeffrey Winters, a Northwestern University political science professor who studies the role elites play in politics, put it more strongly. “Ryan is a litmus test for American oligarchs suspicious of the sort of centrist politics Romney displayed in his years as governor,” he wrote in an email. “Picking Ryan sends a strong signal to the ultra-wealthy that Romney has embraced the core conservative principles of attacking all redistribution from the haves to the have-nots.”