The Centers for Disease Control is investigating a horrifying outbreak of meningitis that thus far has killed four people and sickened 30 others across five states. The infection, caused by a fungus that is particularly difficult to treat called Aspergillus, has occurred exclusively among people who received an otherwise routine injection given to reduce lower-back pain. (This outbreak, though similar-sounding in name, should not be confused with the outbreak in New York City of meningitis and blood-borne infection from a bacteria, Neisseria meningitidis, more commonly called meningococcus.)

Although the investigation is still in progress, early suggestions point to contamination of the injected medication—the drug used in each of the 30 patients, a steroid related to prednisone and hydrocortisone but not to the anabolic steroids athletes use to muscle up, came from the same manufacturer, suggesting a critical and tragic lapse in the facility’s environmental control. And with Aspergillus, the environment is key: Aspergillus is a ubiquitous airborne mold that can cause allergies and hay fever. It grows extremely well in rotting plants and rotting anything. All of us inhale a few dozen spores every day and are no worse for wear. (A mold is one type of fungus the way primates are a type of mammal; yeast—as in baker’s yeast—is another common type of fungus.)

Most people don’t develop Aspergillus infection this way. The more typical patient is one who is at the losing end of immune function—people receiving extremely intense chemotherapy for conditions like leukemia or bone-marrow transplant. When we read that Indianapolis Colts head football coach Chuck Pagano, who just was found to have acute leukemia, was placed into isolation to prevent infection, it is to prevent him from inhaling environmental pathogens such as Aspergillus.

The other way to acquire the infection is via accidental introduction from a surgical procedure (like a steroid injection) or from brutal trauma, as occurred with a related though distinct mold seen after the Joplin, Missouri, tornado. Infection acquired this way is incredibly rare: I have seen exactly one case in almost 25 years as an infectious-disease specialist.

The new outbreak is a bad one for several reasons. First, it’s big and likely to get bigger before the investigation ends. People who received the tainted injections can take weeks and weeks before they become ill. Plus, the anatomic site of the infection is particularly hard to get at with antibiotics. The steroid injection is intentionally placed into the epidural space, which rides just outside the spinal cord. There, close to the exit point of the nerves from the spinal cord into the arms and legs is a perfect place to aim treatment—plus the area has a poor blood supply preventing rapid washout of any medication. But the same poor vascular supply that makes it an attractive target for injections means that antibiotics (or in this case, antifungals) don’t easily penetrate the site. Finally, our current group of antifungals is pretty lame—nowhere near as lean and mean as our impressive arsenal of drugs used to treat bacteria.

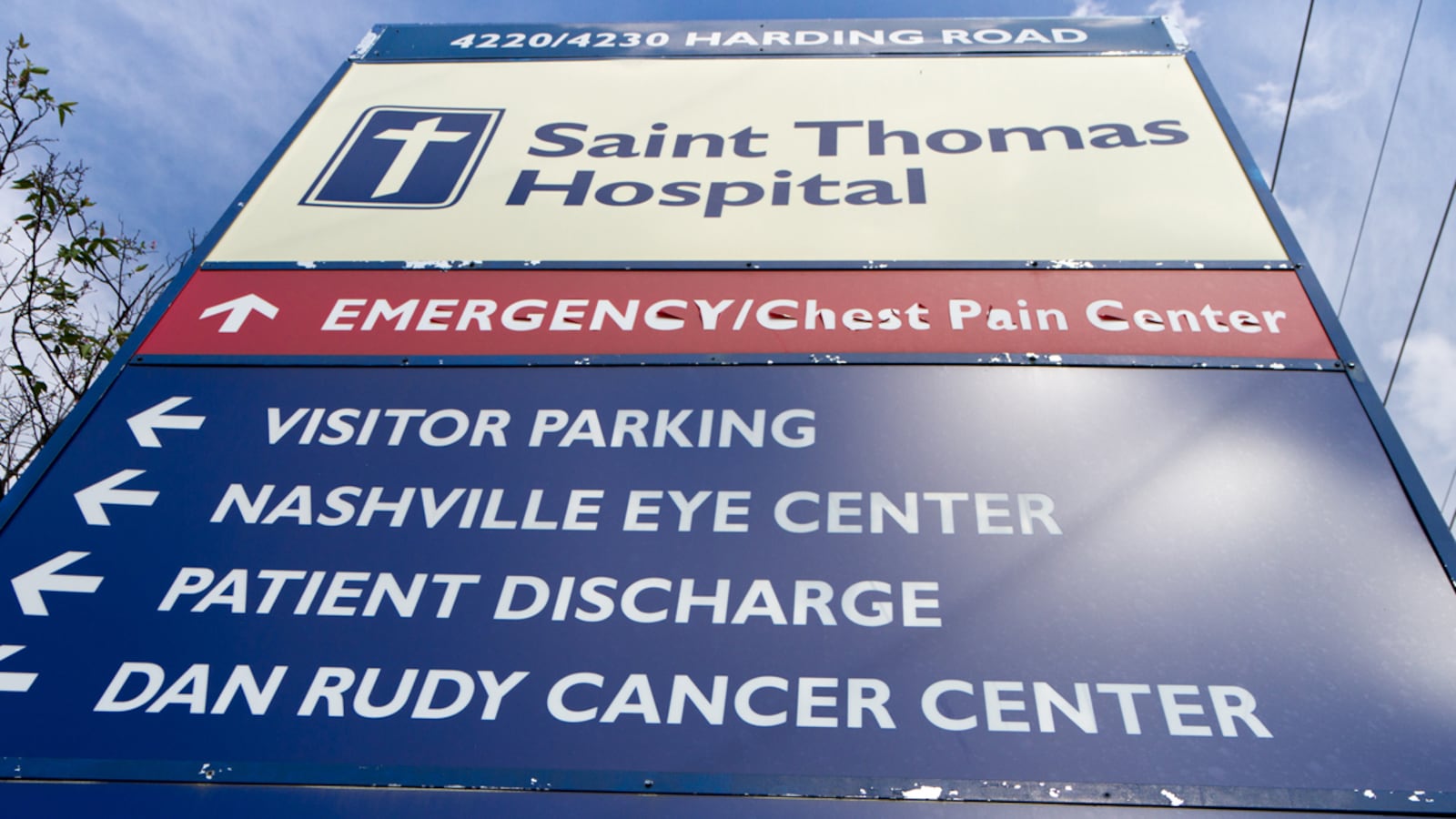

As the outbreak unfolds further, it is likely that the most popular focus will be directed at establishing someone or something to blame: a regulator who didn’t regulate the factory; a sleazy owner who hid manufacturing problems; or perhaps some completely unanticipated flaw in the production that neither thorough regulation nor a caring factory manager could have anticipated. But little attention will be given to the most important part of this out outbreak—why are so many people getting epidural injections for back pain? According to the National Institutes of Health, just about the entire U.S. population has, at one time or another, had back pain that interferes with work or recreation. And we Americans spend at least $50 billion each year on the problem. And the number is rising: almost twice as many Medicare recipients received injections in 2006 than they did a decade earlier (PDF)—about 780,000 Medicare recipients in 2006. And because the intervention is substantially cheaper than major back surgery, insurance companies are inclined to reimburse it fully.

The problem is that there is no convincing evidence that epidural injections work. Countless studies and analyses of the studies have been performed; medical, surgical, osteopathic, chiropractic, and neurologic journals are filled to the gills with such reports. The most optimistic interpretation of the evidence for epidural steroids is that they work a little, briefly, in some people for whom nothing else works. The Cochrane Library, considered the most objective of all collections of experts who examine and interpret already-performed studies, concluded that “there is no strong evidence for or against the use of any type of injection therapy for individuals with subacute or chronic low-back pain.”

The rush to treatment, any treatment, for back pain and countless other chronic conditions is the fault of no one group. We have an unfortunate mix of eager patients, eager doctors, eager drug companies, and eager surgical-supply houses all wanting to make people feel better, albeit for very different reasons. The main rationale for the epidural-injection approach has been its purported safety; the thinking went along these lines: what’s the harm in trying it once or twice—if it works, great—and if not, well at least we tried. The 30 people in Tennessee and nearby states, however, are a grim reminder that in medicine even the most unusual outcome is going to happen eventually if you do a procedure often enough. They are now the sad poster children of the reason why in medicine, sometimes doing nothing is the best thing that a doctor and patient can do.