Proof of Game of Thrones’s excellence is that the quiet phrases are sometimes more arresting than the bloodiest betrayal and revenge. When Varys the Spider, the ultimate scheming courtier, hisses, “I serve the realm,” I don’t doubt that he means it, by his own flickering lights. Varys takes an almost sensual pleasure—his only one, as far as we know—in his secret knowledge and the power it gives him. He is vividly, fearfully aware of how much worse things might get than the rotten, tottering system he upholds. And, of course, if that system fell, he would be nowhere. So he weaves the shadows that power is made of and sighs to himself when the royal executioner beheads brave, naïve Ned Stark.

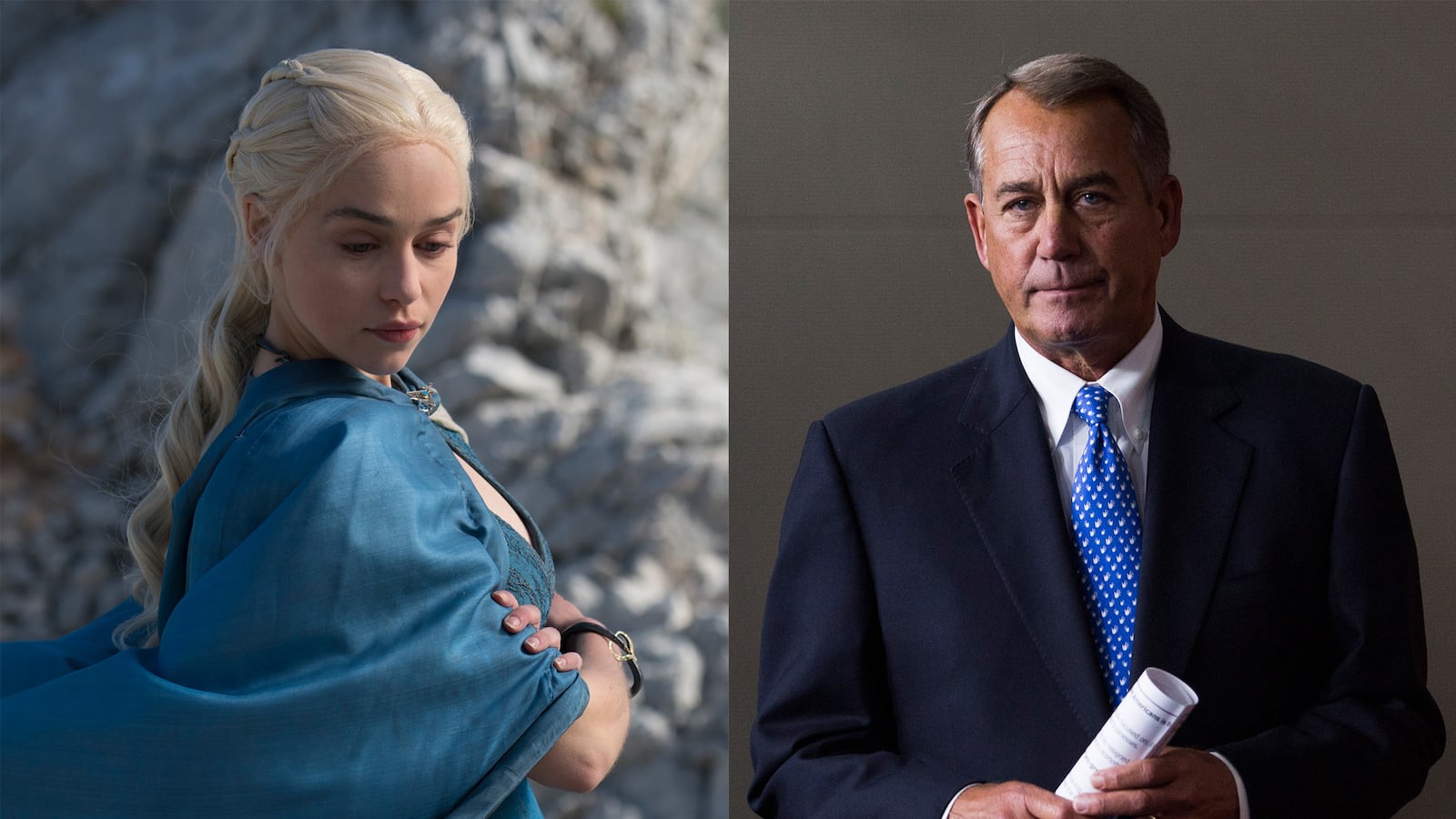

When I hear Varys’s slogan, I think of John Roberts, defending the Constitution by decapitating campaign-finance reform and the Voting Rights Act, perhaps with a moment’s regret at the human cost of his principle. You will have your own D.C. Spider, in whom ambition and principle are so fused that it’s hard to imagine they were ever separate. Mitch McConnell? Harry Reid? John Boehner would have checked for a camera before he wasted a sigh on Ned Stark’s pike-mounted head.

It was instant cliché to say that Martin meets us where we live, and where we are governed. His political cynicism matches House of Cards in channeling despair at Washington. His fantasy is rooted in a picture of politics—and the human heart—as a theater of naked ambition, self-deception, and cruel historical irony. Who hasn’t thought, “Christ, Winter really is coming,” while watching the political class sink climate legislation and bloody itself in debt-ceiling fights?

Did you think of the fratricidal Baratheon brothers, Renly and Stannis, at each other’s throats and squandering a chance to unite the kingdom, when the GOP announced that Barack Obama’s failure was its top domestic priority? And do you ever wish more hard choices could somehow fall to a canny dwarf? (The technocrats of the Federal Reserve are awaiting your call.)

We could hardly get further from the other towering fantasy world in Anglo-American writing: Middle Earth, where only orcs are monstrous, friends are true, and redeeming kings are handsome, long-lived, and pure. No wonder the New York Times review of A Dance with Dragons began, “It’s high time we drove a stake through the heart of J.R.R. Tolkien,” and concluded with a stab at the corpse worthy of sadistic young King Joffrey: “Tolkien is dead. And long live Martin.”

Not surprisingly, Martin’s work has been seen as too cynical, and too smart, for the kind of earnest political appropriation that Tolkien has always attracted, from the Cold War right down to a debate among fans—and the actors! including Aragorn and the dwarf! —about who was the dark, power-mad Sauron, Saddam Hussein or George W. Bush. Martin’s ironies seem to puncture such stuff like Arya’s needle. Some fans even think that Martin’s very-now interest in marginal and misfit characters means he has given up on the idea of a protagonist. In a thoroughly corrupt world, power may be the only interesting thing and powerlessness the only attractive thing. Then both are, in the last reckoning, hopeless.

So it has surprised me to realize that Martin, supposedly a nihilist for our nihilistic time, is a much more interesting key to politics than Tolkien ever was. This isn’t just because he agrees with us that people are complicated, the capital is a cesspool, and you have to keep an eye out for sadists. It isn’t just that he mistrusts the heroic, black-and-white moral language that brings on a dry throat and a sour stomach until Stewart or Colbert cures it.

No, Martin, unlike Tolkien, gives us a world where political philosophy is both possible and—maybe surprisingly— necessary. This anti-moralistic political drama is a morality play on the value of political thought, and the importance of doing it well.

Serious modern political thought begins from two basic points. First, human nature and social life are tragic: they put people into wasteful and often bloody conflict, not because people are awful, but because disagreement, misunderstanding, and competition over the world’s good things are all inevitable. The first English-speaking political philosopher, and still arguably the greatest, Thomas Hobbes is remembered mainly for remarking that human life tended to be “poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

He did not mean that people are nasty and brutish. He meant even reasonable and decently-intentioned people will end up as suspicious as Varys, as scheming as the nihilistic bureaucrat Littlefinger, and as vulnerable as doomed Ned Stark, unless they live under a well-designed government that saves them from constant conflict.

Second, politics is artificial. Its whole point is to create structures of power that make life less tragic. It is how we save ourselves from ourselves. We can’t change human nature, so we must change the circumstances in which it plays out. For Hobbes and the many who came after him, this meant creating a government—Leviathan, he famously called it – that would make cooperation, investment, and generosity possible without constant fear of betrayal and bloodshed.

The great political debates have been about what this government should do. For classical liberalism, it should create markets, so that self-interested competition could go on peacefully. Socialists went further, seeking to overcome, or at least soften, the tragic conflicts of economic life, where one man’s exploitation fed another’s wealth. Democrats—the world-historical movement, not the US political party—insisted that everyone must have a say and the majority’s vision of politics must prevail. Overlapping and conflicting, these different political takes are all answers to the same question: since social life without government is a shapeless disaster, how shall we shape it together instead? This is the modern political question.

In Tolkien’s world, the question never arises. His view of politics is pre-modern: order is natural, each people has its own kind—generally hierarchical, under benign kings or elders—and things go wrong only when that order is broken by the forces of evil and chaos. Those forces may tempt the weak—think of Isildur, Saruman, and poor Golem, a man, a wizard, and a Halfling, all seduced by power and the promise of immortality; but their corruption comes from a lack of virtue.

The answer is to restore more virtuous and courageous rulers. The real source of trouble is the evil Enemy. I heard stories during the Iraq War of American soldiers shooting down foreign fighters whom they called “orcs.” It is hard to imagine anyone who has gone through a few seasons with Martin casting their dehumanized enemies as Lannisters or Wildlings.

For Game of Thrones, the political question underlies everything. The first season is a straightforward tragedy: Ned Stark’s virtues, loyalty and honesty, are a death sentence because Westerosi politics rewards cunning and treachery instead. But, unlike in a classical tragedy, it is not the gods who turn his virtues against him; it is, to use a deliberately clunky and earnest term, the system. His enemies, with the exceptions of Joffrey and various hangers-on, are not sadists, not orcs. Tywin Lannister, the financier-lord of the Starks’ arch-enemies, and Petyr Baelish, the nihilistic bureaucrat nicknamed Littlefinger, are perfectly rational actors.

They thrive in a system that translates wealth directly into power and power back into wealth again, where the most dangerous thing is to fail and the easiest way to fail is to lose sight of where you advantage lies. You could find plenty of Lannisters among investment bankers and political strategists, most not bad people in any interesting way, each one expertly playing his part within the rules. And you would find a Supreme Court and a President quick to back up and abide by those rules.

The story’s slow rotation of perspective, in which two-dimensional villains like Jaime Lannister wax sympathetic while the brave Catelyn Stark wanes into obsessive vengefulness, dissolves any lingering sense that bad people are at the root of the problem, that the solution will be a virtuous king’s victory. Through its wrenching, eventually exhausting series of betrayals, Game of Thrones asks, “Is treachery unavoidable?” and answers: In this world, yes.

Game of Thrones knows this is a political question. It does not pull the fake-deep trick of treating political horror as a symptom of original sin—as if we were all one bad decision away from Syria, Iraq eight years ago, or Somalia in the 1990s. Those are all products of political systems gone badly awry—through schism, invasion, or breakdown. Martin’s world is not divided between corrupt order and worse chaos: it is rich with multiple orders.

The individualistic democracy of the Wildlings haunts Westeros to the North, in many ways a humanly better system than the legitimacy-obsessed, power-hungry hierarchy with its capital in King’s Landing. The Free Cities across the Narrow Sea lack a semi-feudal monarchy’s fixation on the Throne, but their money-greedy pragmatism and embrace of slavery are a harsh judgment on purely commercial cultures. We see a peaceful and egalitarian culture, the Lamb People (though they don’t last long when they meet the Dothraki, a kind of Mongol Horde). And feminism is a rising challenge in Westeros. Rogue female knights and emancipated Wildlings are approaching the center of the story. Cersei Lannister, the queen poisoned on her thwarted will-to-power, and Sansa Stark, the little girl grown up into her own pathetic princess fantasies, sit at its center, condemning the gender politics of the realm by their very existence, like a medieval reprise of Betty Friedan’s alienated and miserable housewives.

Meanwhile, Daenerys Targaryen, the conquering queen-in-waiting, is getting a political education during her long procession toward Westeros. She makes her first scars on the world as an Emancipator, a blond Spartacist, Abe Lincoln with dragons. The disasters that follow her freeing the vast slave cities of the eastern deserts teach her some very Hobbesian lessons. It is not enough to liquidate the most brutal forms of power and tell people they are now free. (Remember Iraq?) The political problem is to secure order in a way that makes good on Dany’s humane and egalitarian passions without feeding the emancipated into the furnace of chaos.

It could be that the story will veer into a nihilistic bottom line: nothing works; we’re all fucked. Martin might also fall back on the Romantic nihilism that loves the rebel misfits—gender-nonconformist Arya Stark, strong-hearted bastard Jon Snow, and the rest—but expects nothing from them except short, beautiful lives. I doubt it, though.

This story takes politics too seriously to shrug off its basic problems. Hobbes learned about human nature from the cynical political histories of the Roman Tacitus, and I suspect the Hobbesian passion to think through political order cohabits in Martin’s furry head with the Tacitean aesthetic of betrayal, perversity, and irony. (I’m also cheating on my 1990s humanities education by assuming the “author” of Game of Thrones has something in common with a certain George R.R. Martin who broke his usual, commercially prudent political silence in 2012 to denounce Republican voter-suppression laws as “reprehensible” and “despicable.” The author of that indignant blog post seems unlikely to dissolve all political conviction in an acid bath of cynicism.)

There are plenty of hints that, if humanity is going to survive Martin’s winter, it will have to find a political basis for cooperation. The democracy of the Wildlings, the (ever corrupted) law and honor of the Westerosi, the pragmatic commercial spirit of the Free Cities, the empire of emancipation sweeping West as Daenerys’s Dothraki turn into an army of liberators, will all have to become something more than any one of them.

Of course Martin’s story isn’t entirely secular or naturalistic. Older, non-human principles play a part. The Starks, who provide the series’ most charismatic heroes so far, are magically bound to dire-wolf familiars, a theme hinting at something ecological and mystical that is growing in power as winter approaches. In A Dance of Dragons, Martin sent young Brandon Stark, whose crippling defenestration began the series, to commune with ancient Earth-spirits. Those spirits have a cosmological rendezvous with the other religions at play in the series, the Olympus-like pantheon of the Seven and the monotheist Lord of Light.

But where Tolkien’s magic bespoke Catholic religion fermented into myth, Martin gives us religion as an opportunistic byproduct of political failure. When disorder reigns, priests and fanatics rush in with otherworldly reassurance – and to claim a new share of political power for themselves. His invented religions are real forces in Westeros, but they are entangled with, dependent on, his all-too-familiar politics. Martin has invested too much intelligence in the politics of his imagined world to hand it over to a theological contest at the end.

Let’s come back from Westeros proper to the Westeros-besotted US. It is, after all, our fantasy. Westeros exists because it fascinates us, and for no other reason.

What does the national love affair with Game of Thrones reveal? In fantasy, suppressed desires come out when they can’t get footing in the real world. On the simplest level, Martin just gives us an update on what magical stories and war sagas have always offered: heroes, love, betrayal, and tragic death. His version is leavened with enough cynicism and psychological realism that we don’t feel too dumb while indulging ourselves.

On another level, the orgy of cynicism and treachery is the fantasy. Despair and mistrust pulse just beneath the surface of our pious but stupefyingly venal public life, and having them out in the light, vivid and naked and exaggerated, serves up the sort of cathartic relief that more traditional pornography must have in a different time, when sex was the ever-present, ever-disowned pivot-point of psychic tension. (The elaborate, well-lighted sex that forms an emotionally neutral backdrop to GoT, like the furniture in Downton Abbey, is a kind of visual pun on the word fantasy in our culture, so drenched in commodified erotics that you could hardly build an audience on it.)

But most interesting and promising is that Game of Thrones does not follow Tolkien into the fantasy that politics could ever be dissolved into the virtue of a good king. In the last decade, Americans have elected, with considerable struggle and passion, a president of great symbolic importance and considerable virtues, including intelligence and personal rectitude. We have seen the limits of good kings.

Meantime, our systems—the real concern of politics—are failing us. A constitutional structure set up to hobble political action is working too well, as Congress deadlocks and the Supreme Court picks away at the few real achievements we can manage—campaign finance reform, health care. The market, as economist Thomas Piketty and others are showing, has been systematically rewarding the wealthiest as social mobility breaks down.

Everyday life produces climate change as a passive byproduct. Only the Romantic wing of the Tea Party believes, in a kind of bastardized Tolkienism, that we could solve it all by getting back to our natural American Constitution and our God-given truly free market. Our next protagonist has to be more than a good king. It—not he—has to be a movement for better systems.

It is perfectly possible to watch Game of Thrones without thinking of any of this, but unlike some other fantasies, Game of Thrones denies none of it. Maybe, somewhere in our current favorite object of escapism, there is an obscure hunger to confront these hard facts. Tolkien said that Middle Earth prepared readers, in a subtle and ambient way, to accept the Christian, and specifically Catholic, worldview. Strange as it seems, maybe Westeros and the lands beyond are doing the same for a real grappling with politics.