"We have to be about how we bring people in,” Deval Patrick said when he announced his late entry in the Democratic field this week, offering himself as the only candidate who could beat the candidates to his left and occupy the middle ground needed to beat Donald Trump. “How we bring people along and how we yield to the possibility that somebody else, or even some other party may have a good idea, as good or better than our own."

Patrick certainly has a history of yielding to the possibility that someone else might have a better idea, especially when it has benefited his own bottom line. After leaving public office, he worked for Texaco (not exactly the greenest company) and Bain Capital (best known as the basis for Mitt Romney’s fortune). But what should really cause voters to pause is the work Patrick did right before becoming governor of Massachusetts. While Patrick says he’s running for president “to build a better, more sustainable, more inclusive American dream for everyone,” it wasn’t long ago that he was profiting by destroying it.

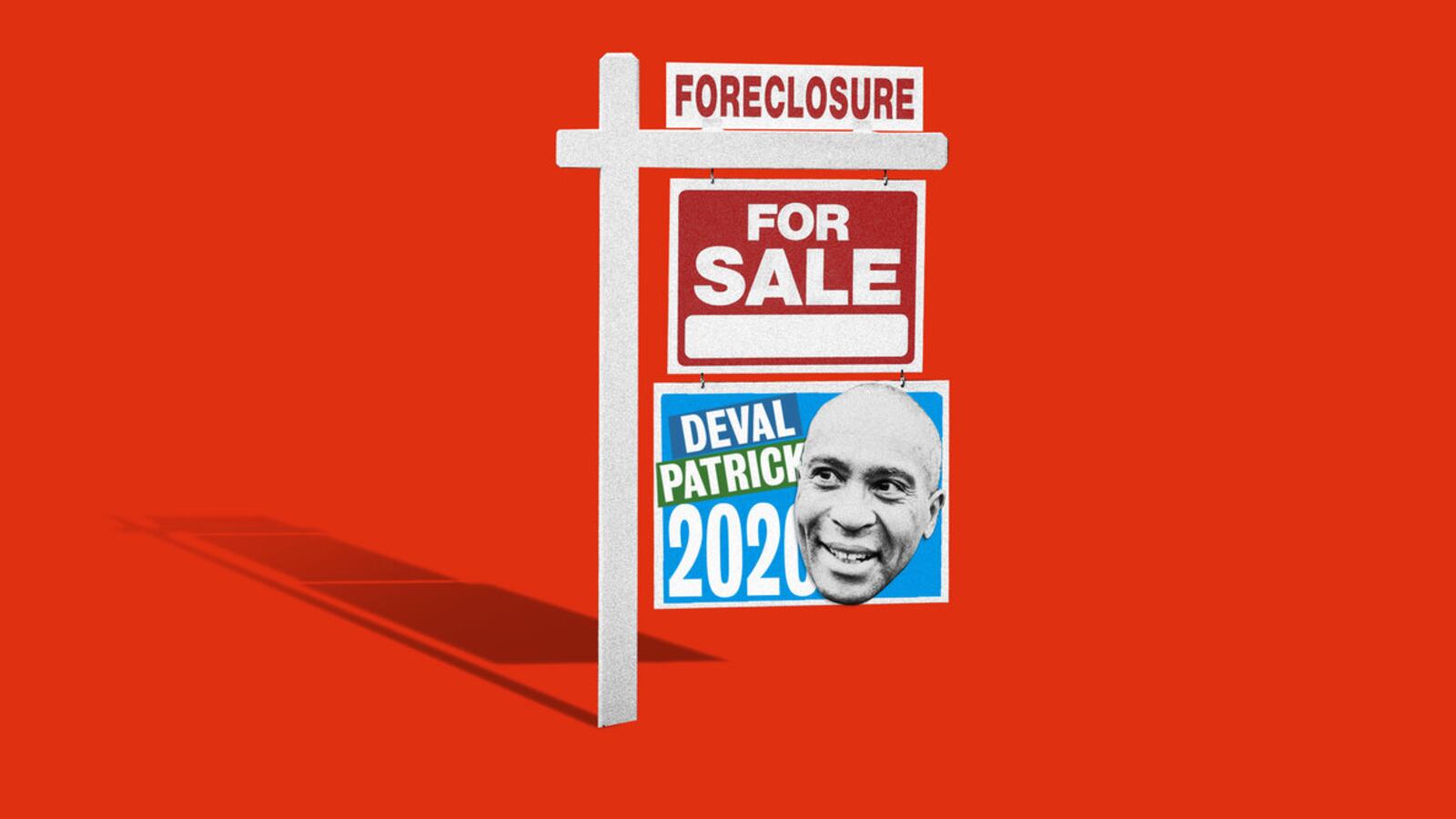

From 2004 to 2006, Patrick was on the board of ACC Capital, the corporate parent of Ameriquest, the nation’s largest originator of subprime loans—described as one of “the worst” lenders in the country by the Treasury Department. This wasn’t a mortgage company that helped families buy homes—93 percent of its loans were refinances. Instead, it used high-pressure sales tactics to get people who already owned their homes to refinance themselves out of honest, straightforward mortgages and into loans that featured skyrocketing interest rates and balloon payments. It particularly targeted the African-American community.

Patrick was part of a small gang of moneymen who cashed in when the economy crashed a decade ago. Most of the members of this club are Republicans close to President Donald Trump. Their ranks include Steve Mnuchin, now the treasury secretary. He bought a failed Southern California bank off the FDIC—paying the government nothing—and then raked in more than a billion dollars in subsidies as his ownership group foreclosed on 137,000 families, including 23,000 seniors. They also include Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who did much the same in Florida, taking more than a billion dollars in subsidies at BankUnited, a failed bank in Florida. And the president’s close friend, Tom Barrack, who used the wave of foreclosures to build a rental empire of 30,000 homes from California to Florida; as well as Republican cash cow Steve Schwarzman, the chairman of Blackstone, whose company gobbled up 80,000 houses, most of which were owned by families before the bust. Together, these men sent homeownership spiraling downward for nearly a decade, until, in 2016, it bottomed out at its lowest level in 51 years.

This economic calamity hurt people of all backgrounds—nearly 8 million families lost their homes in the bust—but it was particularly devastating for people of color. Because they were typically charged higher rates and targeted for predatory loans by companies like AmeriQuest, African-American and Hispanic families were foreclosed on at more than twice the rate as whites.

None of this profiteering would have been possible without men like Deval Patrick, who oversaw the companies that made bad loans in the first place. Ameriquest was everything that was rotten at the heart of the housing bubble—more of a “boiler room” than a bank, a Los Angeles Times investigation found, “deceiving borrowers about the terms of their loans, forging documents, falsifying appraisals, and fabricating borrowers’ income to qualify them for loans they couldn’t afford.” The loans, once made, were “juiced” with “hidden rates and fees.” Up and down the organizational chart were managers and executives well aware of the wrongdoing, including those at the top.

Patrick joined the board after it was already under investigation and has argued he used his position to help change the bank’s culture. In May 2005, with Patrick on its board, the company settled a $50 million class-action lawsuit charging it had defrauded borrowers in four states. The following year, it agreed to pay $325 million to end a lawsuit brought by 49 state attorneys’ general that alleged systemic fraud.

Patrick quit the board shortly after the $325 million settlement. By that point, he was running for governor of Massachusetts and his Democratic rival, state attorney general Tom Reilly, who brought the case, had called him out. “This is a very bad company engaged in despicable practices,” Reilly told a press conference. “I would personally have nothing to do with them.”

In a response that sounds similar to his current campaign rhetoric, Patrick retorted that “progressives are sometimes uncomfortable in principle with people who work for companies,” adding that he had “never left my conscience at the door.” But there’s no evidence that he raised any objection to Ameriquest’s actions when he was inside the door. Indeed, after then-President George W. Bush appointed Ameriquest’s principal owner, Republican mega-donor Ronald Arnall, ambassador to the Netherlands in 2005, Patrick wrote to leaders of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, including current Democratic rival Joe Biden, urging he be confirmed.

Since 1992, no Democrat has captured the party’s nomination without winning a majority of African-American primary voters. As one of only two African-Americans elected governors in U.S. history, Patrick’s supporters are hoping that he will inspire these voters. But thanks to companies like Ameriquest, the African-American community in particular was devastated by the foreclosure crisis—and today the homeownership rate among African-Americans has fallen to levels not since the Jim Crow era. With no home equity, many black and brown families are left with only debt to pass on to their children. The average black family has less than $10,000 to its name, and nearly one in three black households are literally worth nothing, because their debts are greater than or equal to their assets. Hispanics fare only slightly better. Government data show the median Hispanic family is worth $18,000, while about one in five Hispanic families have have a zero or negative net worth. Suffice it to say, Patrick’s net worth was not harmed by his employment at Ameriquest.

Today, Patrick argues he’s the best hope for the Democrats because of the “leadership I have brought to settings in the private sector and the public sector, the kind of leadership I want to bring right now." For homewreckers like Steve Mnuchin, that must have sounded a lot better than the declarations of the other Massachusetts presidential candidate. After all, it wasn’t just that Mnuchin, Ross, Barrack, Schwarzman and the others made fortunes by ripping off working class Americans—it’s that they ably took advantage of bad government policy and legal loopholes. That’s some real yielding to possibility.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with going into the private sector and making a lot of money, but how you do it makes a difference, especially if you’re running for president. Mnuchin and his Republican cohorts loved nothing more than going after a homeowner who could be trapped under a mountain of debt. So did Ameriquest. For millions of Americans, that was bad news, but for Deval Patrick, it was lucrative, and if he wins in 2020, he’ll get to enjoy a sort of security he so eagerly helped deny others. After all, there’s no outstanding mortgage on the White House.

Aaron Glantz is a senior reporter at Reveal and the author of Homewreckers: How a Gang of Wall Street Kingpins, Hedge Fund Magnates, Crooked Banks, and Vulture Capitalists Suckered Millions Out of Their Homes and Demolished the American Dream (published by Custom House). Emmanuel Martinez contributed reporting.