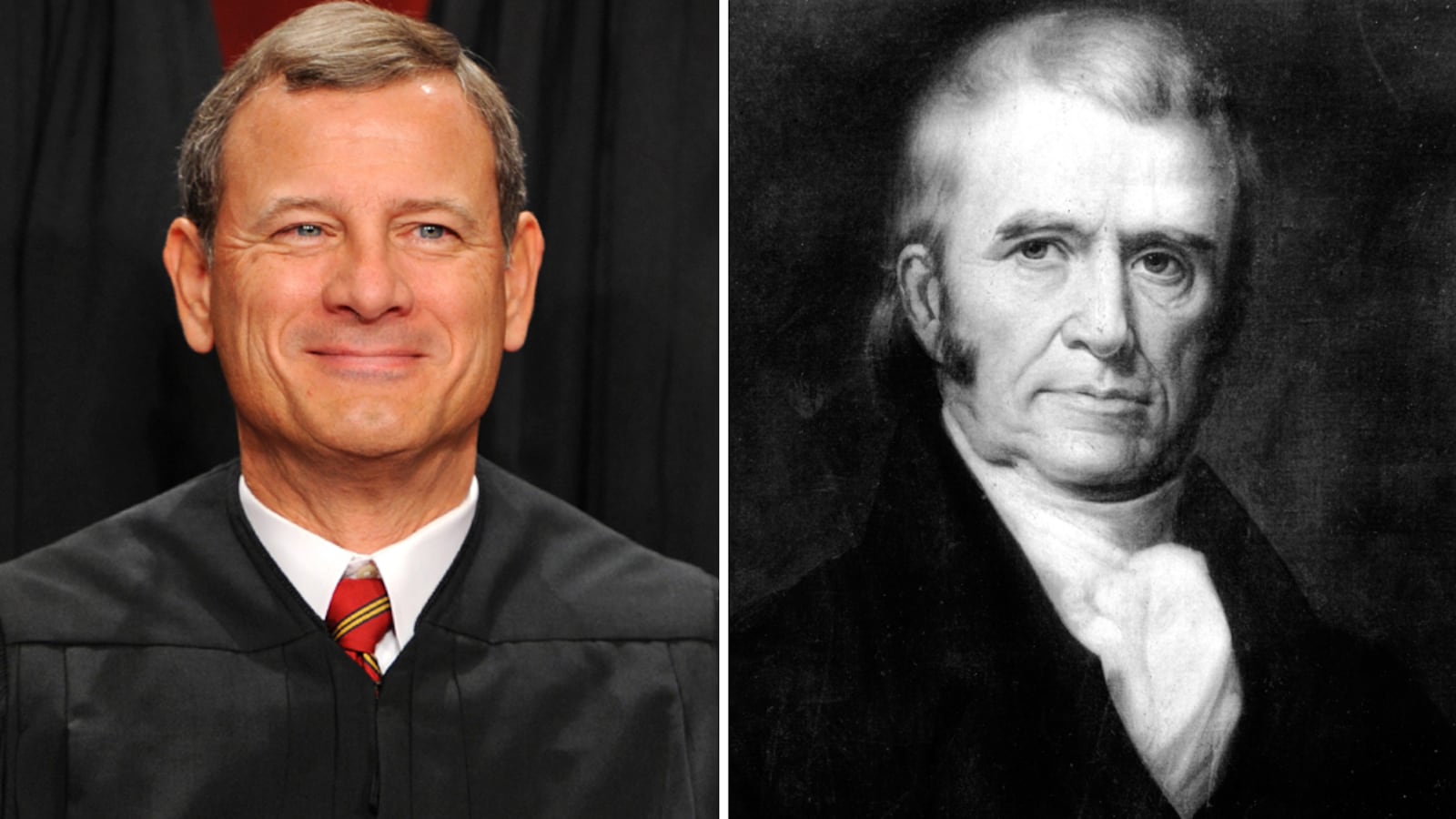

The cases are 209 years apart, but just below the surface, the similarities between Marbury v. Madison, the landmark Supreme Court case establishing judicial review, and today’s decision upholding the health-care law’s individual mandate are striking.

In his 2008 book The Activist, Lawrence Goldstone detailed the circumstances of Marbury, which addressed the power of the court to strike down federal laws.

Goldstone wrote of Chief Justice John Marshall, a federalist who wanted to avoid granting more authority to the new president, Thomas Jefferson, “He knew all too well that if he sided with his fellow federalist [William Marbury, who had filed a lawsuit against Jefferson’s administration with the Supreme Court], Jefferson would simply refuse, and Marshall had no means to compel him to comply. The court’s authority would therefore be weakened, thus defeating the federalist scheme to maintain its power through the judiciary.”

But deciding the other way would have been using the federalist-heavy courts to “strengthen Jefferson’s power,” which would have been “equally unpalatable.”

After this morning’s ruling, law professor David Bernstein wondered about the Supreme Court’s authority (or at least the public perception of it): “[W]as [Roberts] responding to the heat from President Obama and others, preemptively threatening to delegitimize the court if it invalidated the ACA?”

There is no reason to think that President Obama would not have complied with today’s ruling if it had gone the other way, but that doesn’t mean he would take it lying down. As the political reporter Marc Ambinder tweeted earlier this week, “The [White House] has exec[utive] orders [ready to go] if ACA is struck down. Their content and timing I don’t know. But they’ve got contingency plans a-plenty.”

The bottom line is that both Marshall and Roberts were writing their opinions in the face of intense political pressure and competing views of the proper scope of government power. In 1803, as Goldstone wrote, “Marshall found a way through the thicket.” Roberts did the same today.

How did they do it? In both cases, they started out with a nod to the opposition.

“With inspired misdirection, he began his opinion with a complete validation of Marbury’s claim,” Goldstone wrote of Marshall.

Likewise, Roberts began his opinion today by holding that the individual mandate could not be upheld under the Commerce Clause, which until relatively recently has permitted the federal government to regulate in countless areas with little court intervention. Concluding that the mandate “cannot be sustained under a clause authorizing Congress to ‘regulate commerce,’” the chief justice even went so far as to raise the hypothetical “broccoli” mandate—a pet issue of the mandate’s opponents that was raised by Justice Antonin Scalia at the oral arguments for the case in March. (This misdirection is also likely what led CNN and Fox News to mistakenly report that the mandate had been struck down.)

Next, each man issued his ruling in favor of the president, but simultaneously protected another interest.

In Marbury, Marshall struck down the law at issue, which resulted in a rejection of Marbury’s claim. This prevented Jefferson from losing the suit, but also provided Marshall with a win for the federalists’ aim to strengthen the judiciary.

Today, Roberts upheld the individual mandate under the federal constitutional authority to tax, which resulted in a rejection of the mandate opponents’ claims. This gave Obama a clear win on health care, but laid a potential trap for future congressional efforts to regulate commerce.

The significance of this approach wasn’t lost on close observers of the court.

Roberts “reached out broadly to impose unprecedented new restrictions on the powers of Congress in its ability to address important national questions of social welfare,” wrote University of Pennsylvania law professor Tobias Barrington Wolff.

Slate’s Tom Scocca concurred. “By ruling that the individual mandate was permissible as a tax, [Roberts] joined the Democratic appointees to uphold the law—while joining the Republican wing to gut the Commerce Clause (and push back against the Necessary-and-Proper clause as well).”

But some say whatever damage was inflicted on the Commerce Clause today won’t be felt too deeply.

“It will have almost no effect on legislation moving forward, because the opinion makes clear that what you can't do through the Commerce Clause, you can do through the General Welfare Clause,” Jack Balkin, a professor at Yale Law School, told The Daily Beast. (Extra points to Balkin, who predicted today’s outcome.)

William Marshall, a former deputy White House counsel, likewise told The Daily Beast, “This is a very rare instance in which Congress believed there was a need to regulate inactivity in order to achieve its goals and I am not sure that there are likely to be many others.”

“The lasting impact of these portions of the court’s ruling will take years to assess,” Wolff said, noting that the portion of Roberts’s opinion discussing the Commerce Clause could be diminished because it was not, technically, necessary to the ruling—a view countered by Roberts himself in another part of his opinion.

“Nonetheless, their disruptive potential is extraordinary.”

It took 50 years after Marshall penned his opinion in Marbury for the Supreme Court to strike down another act of Congress. But more than 200 years later, the disruptive potential of judicial review remained on full display.