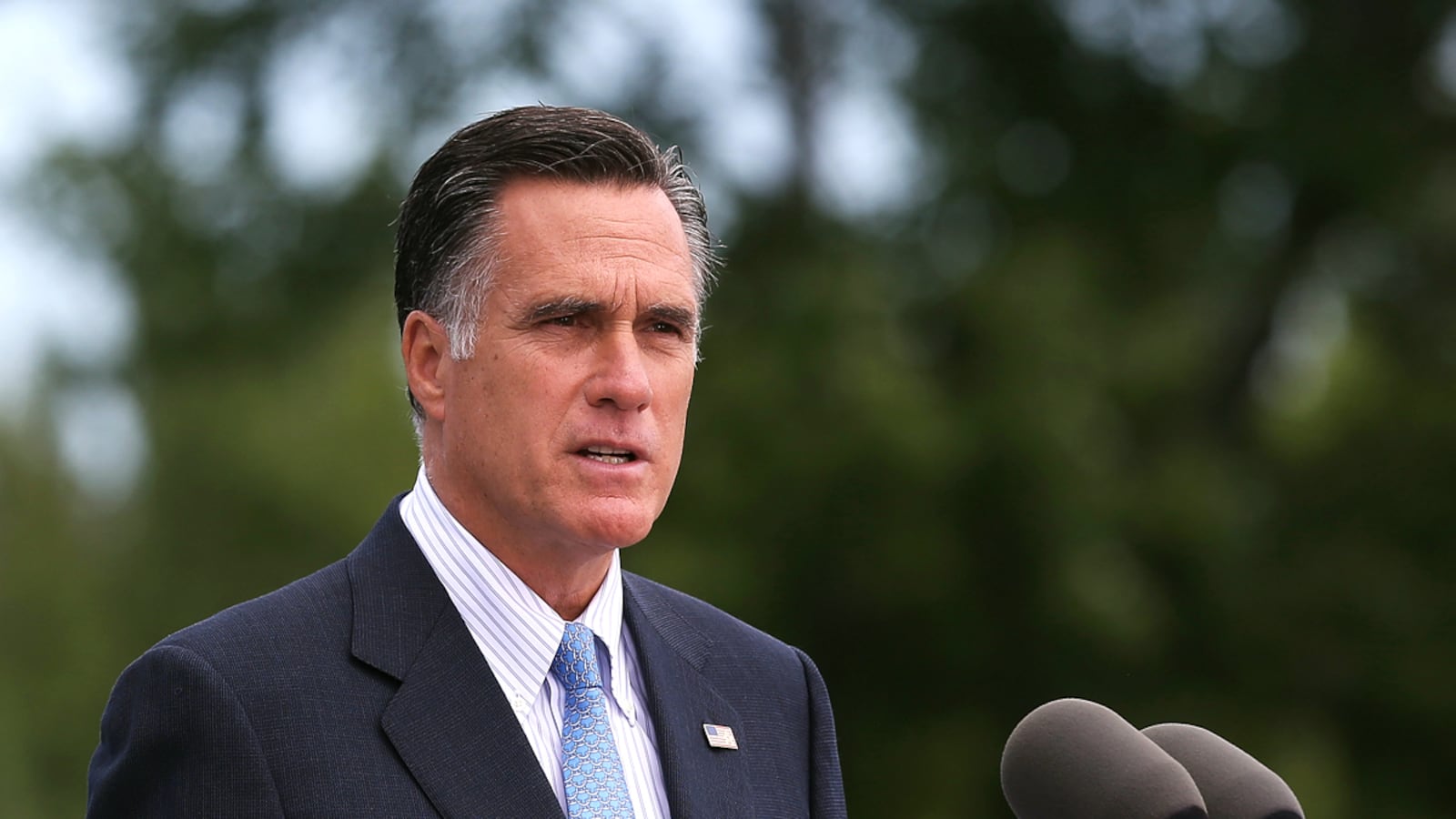

Lake Michigan has always figured prominently in Mitt Romney’s personal history. During a 2011 visit to Michigan, his wife, Ann, talked about growing up at her family cottage on the lake and spending “all our time swimming” there. She said she celebrated her 16th birthday with Mitt at Michigan’s official summer residence on Mackinac Island, while Mitt’s father, George Romney, was governor. That’s when she says she fell in love.

In certain circles, Romney’s legend as a defender of the lakes is well-established: when John Nevin, a former Michigan environmental official, endorsed Romney’s 2008 presidential bid in the Detroit Free Press, he wrote that Romney was “the only sure bet to restore, protect and sustain our Great Lakes.”

Nevin alluded to the disturbing denigration of the lakes by chemical pollutants, and wrote that Romney “believes the cleanup of these toxic hotspots” has been “far too slow,” bogged down by “legal wrangling.”

But in reality, Romney’s own business career connects him closely to those “toxic hotspots”—in particular, his relations with the two companies primarily responsible for the contamination of Lake Michigan.

Shortly after graduating from Harvard Business School in 1975, Romney began working for Boston Consulting Group, where one of his biggest clients was the now-defunct boat-engine and powerboat manufacturer Outboard Marine Corporation.

“Mitt was out working in the plant and in my office,” said Charles Strang, who was then OMC’s CEO and chair. “I was one of the first persons to ever employ Mitt.”

From 1953 to 1976, OMC dumped from 1.1 to 1.7 million pounds of a liquid chemical, PCBs, in Lake Michigan. OMC bought approximately 11 million pounds of hydraulic fluid containing PCBs from Monsanto, the sole American producer of the coolant and lubricant used in OMC’s die-casting machines. While PCBs were found “possibly carcinogenic” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 1978, and “probably carcinogenic” in 1987, they’d been called “objectionably toxic” since the 1940s and were partially banned by the government in 1973. PCBs have been shown to have chronically toxic effects on the thyroid, stomach, liver, kidneys, and immune system. Congress passed a complete ban of PCBs in 1976, but by then the damage was done.

In a 1996 report, the Environmental Protection Agency projected that certain fish species in Lake Michigan would not reach acceptable PCB levels until 2046, warning that frequent consumption of large lake trout and salmon could lead to an increased risk of cancer.

OMC wasn’t the only offender: Monsanto also shipped PCBs to Green Bay/Fox River paper companies and the Tecumseh Product Company in Sheboygan, two Wisconsin Superfund sites on the lake, as well as to plants along the Milwaukee and Kinnickinnic Rivers, all of which added PCBs to the lake. But in a 1981 report, the EPA identified the air, ground and water pollution produced by OMC in Lake Michigan as the cause of “the highest known concentrations of uncontrollable PCBs in the country.” OMC even repeatedly dredged the harbor at Waukegan, Ill. where its headquarters and plant were located, to maintain its 23-foot depth, dumping the PCB-contaminated sediment it collected in open water as far as six miles offshore.

The EPA sued OMC in 1978, adding Monsanto as a defendant in 1980, but the cleanup effort was delayed for a dozen years, in part because OMC refused to allow EPA inspectors onto the site, even ones with a warrant.

In 1986 a federal appeals court found that OMC and Monsanto “caused the PCB problem in the harbor,” “fought the government every possible inch of the way,” and were “a major reason why the PCB problem has not been resolved.” Currently, an $18.5 million cleanup funded by President Obama’s stimulus program is razing the OMC plant, trying to complete the job begun in the 1990s by the EPA.

Strang, now 91, remained a director of OMC until 1996. He told The Daily Beast that Boston Consulting was hired to suggest strategies to combat new Japanese competitors. He said Boston Consulting was not asked to advise on dealing with the PCB crisis, though BCG was certainly working for Strang when the crisis exploded.

Romney played a much larger role with Monsanto, however, helping to craft the corporate strategic response to the PCB and other controversies that dogged the company in the late 1970s and early ’80s. He did so as a consultant for Bain & Company, which Romney joined in 1977 after leaving BCG. He stayed at Bain until 1985, when he took charge of its spin-off Bain Capital. Monsanto was Bain & Company’s biggest client and Romney quickly assumed a pivotal advisory role with the chemical colossus. He was such a hit with company brass that Ralph Willard, a Bain founder and the team leader for the company’s decade-long consulting work with Monsanto, told the Boston Globe in 2007 that Monsanto executives started bypassing him and going directly to Romney. Willard said that Romney had so mastered the chemical industry issues of the late 1970s that he sounded like he went to engineering school rather than business school.

In the same article, Monsanto CEO Jack Hanley said of Romney: “Every contact we had, I came away impressed.” Hanley, along with Bain & Company founder Bill Bain, became so close to Romney that he came up with the idea in 1983 of creating Bain Capital for Romney to run. Former Bain and Monsanto executives say that the Bain team was involved in the company’s tactical response to the multi-faceted PCB controversy.

PCBs put Monsanto in the headlines throughout Romney’s service as a strategic adviser, with the company continuing to insist that the chemicals were harmless. Dan Quinn, a Bain senior manager during some of the Romney years, told The Daily Beast, “Romney certainly would have known about those issues [PCBs] to the extent they were being raised at that time.”

Asked if Romney and the Bain crew at Monsanto knew the details about the company’s PCB problems, Earl Beaver, Monsanto’s then-director of waste minimization and the Chair Emeritus of the Institute for Sustainability, said Romney and the other Bain employees at Monsanto knew of the company’s PCB problems: “They were aware of it. In fact, that was considered one of the negative factors of the company’s chemical business—the public reaction to chemical emissions and some of the downstream consequences of the people using the chemicals.” Beaver said Romney “would talk to more of the higher muckety-mucks,” such as Hanley, about these issues.

Like other Monsanto executives who spoke to The Daily Beast, Beaver said Bain and Romney played a key role in repositioning Monsanto after the PCB scandal exploded, which occurred at the same time that the company’s pivotal role in the manufacture of Agent Orange led to lawsuits from Vietnam veterans. Bain was “looking over the whole corporate business structure,” said Wayne Withers, Monsanto’s in-house counsel from 1968 to 1989. Bain helped move the company away from its chemical core and into agricultural and biotech products, according to these sources, while Monsanto continued to fight to limit the damage from its PCB/dioxin history.

Ironically, it was Mitt’s father, George, who in the 1960s turned Lake Michigan into a sports fisherman’s paradise by stocking it with fatty coho salmon from Oregon, a fish that turned out to be “the perfect repository” for PCBs. Larger cohos were later found by the EPA to contain up to 1540 times the current permissible PCB limit. In 1968, George Romney’s lieutenant governor, William Milliken, hosted a “coho victory celebration” dinner, just a few months before the FDA seized 34,000 pounds of the fish as “unfit for human consumption.”

But years later, Mitt was still apparently interested in doing business with the lake’s polluters. Strang recalled a phone call from Romney in which he made a bid to acquire OMC on behalf of a client he didn’t name. “I told him it wasn’t enough money,” Strang said. Strang says Bill Marriott, the CEO of Marriott International, a close friend of Romney’s, and a director of OMC, “kept me posted” on Romney over the years, and that Romney had even once called him to try to convince him to use Bain & Company as a consultant.

Strang said Romney ‘s bid call occurred “probably in 2000,” before OMC filed for bankruptcy in December of that year. If that is accurate, it might contradict Romney’s contention that he had “no ongoing activity or involvement in the affairs of Bain Capital” after February 1999, when he took charge of the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City—a departing date he’s sworn to in financial disclosure filings. Asked about Strang’s comments and his interactions with Romney, campaign spokeswoman Andrea Saul responded only to the question about this alleged phone call, emailing “Governor Romney has no recollection of the call you cite.”

In 2001, the Canadian company, Bombardier Recreational Products, bought OMC’s boat-engine division out of bankruptcy, and in 2003, Bain Capital bought 50 percent of Bombardier. Romney was certainly in touch with Bombardier at the time of the conversation Strang says occurred, announcing a multi-million dollar sponsorship deal with the company in October 2000, when Romney was running the Salt Lake Olympics. Bain still owns the OMC engine lines and, since its retirement package with Romney entitles his family to a multi-million share of Bain profits annually, Bombardier’s OMC products are even now contributing to the Romneys’ bottom line.

The Daily Beast reached out to representatives for Bain & Company multiple times but received no response.

**

Several OMC executives, including Strang, told The Daily Beast that Monsanto never warned them of the dangers of PCBs, and that’s why OMC sued Monsanto in 1978. OMC attorney Hugh Thomas said: “We were one of the largest customers, if not the largest, of Monsanto for this fluid, and they did not advise us of any potential problem,” even though “Monsanto knew PCBs were a problem.”

Strang said that “it’s a mystery to me to this day” how Monsanto got out of the EPA lawsuit, as it did in the mid ’80s, without paying any compensation. Neither representatives for Monsanto nor the company’s attorneys responded to requests for comment, but the company appears to have benefitted from the EPA’s eventual decision to seek dismissal of its own complaint, preferring to do the cleanup it self and seek triple damages afterward. Instead, OMC alone entered into a consent order with EPA to pay for the initial cleanup.

Monsanto’s alleged deceptive PCB practices were detailed in a lawsuit that the company and a spin-off settled in 2003 for $700 million. The case was filed in 1996 by residents of Anniston, Alabama, one of two locations where Monsanto manufactured Pydrauls, the PCB hydraulic fluids. The Anniston plant was closed in 1971, five years after a company researcher put 25 healthy fish in an Anniston creek and watched all of them die in four minutes, many losing all their skin. But Monsanto continued Pydraul production elsewhere, supplying customers like OMC. A 1970 directive about Pydrauls sent to a dozen top Monsanto executives said: “We can’t afford to lose one dollar of business.” An internal 1976 Monsanto memo indicated that “if a question comes up” about PCBs in general, company officials should “avoid any comments that suggest liability” and any “medical comments.”

As late as 1979—when the 1976 ban went into full effect, and when Bain was apparently deeply involved in every element of the company—Monsanto was still selling PCBs if customers would indemnify the company against legal liability.

Romney is still keeping his ties to Lake Michigan—he ended his recent six-state bus tour there, where he and Ann waded ankle deep into the lake. The tour had started in Milford, N.H., an hour-and-a-half drive from Romney’s summer home in Wolfeboro. Just an eighth of a mile away from the Milford Oval, where Romney and his wife spoke, sits the Fletcher’s Paint Works Superfund site. A federal court found that it was contaminated by “a glut” of PCB Pydrauls supplied to General Electric by Monsanto. A second Monsanto PCB Superfund site, which contaminated 40 percent of the town’s water supply, is two miles away.

Even in the small towns where Romney traveled to plant his flag, his corporate clients had already planted theirs.

Research assistance was provided by Elizabeth Terry, Danielle Bernstein, Loretta Chin, Alina Mogilyanskaya, and Joseph O'Sullivan.