If you or a loved one are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please reach out to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. You can also text or dial 988.

Until Demi Moore plays her in the upcoming season of Ryan Murphy’s Feud: Capote’s Women, Ann Woodward will remain a forgotten figure of social status and scandal. She overdosed on Seconal in October 1975, after a new Truman Capote short story dredged up her past infamy as the shotgun slayer of her millionaire husband, William Woodward Jr. She was exonerated in the 1955 shooting, which was ruled an accident inspired by fears of a prowler in the couple’s wealthy Long Island neighborhood.

In the investigation of Roseanne Montillo’s Deliberate Cruelty: Truman Capote, the Millionaire’s Wife, and the Murder of the Century, Woodward probably killed her husband to circumvent a divorce that would have left her broke and cast out of the New York society she had fought so hard to enter. The event was a lurid scandal in its day.

A research librarian by trade, Montillo used COVID-19 isolation to gather and synthesize newspaper accounts and police and trial records, describing the lead-up, shooting, and aftermath. She also shows the parallel track of Truman Capote, whose eventual literary use of the event influenced Woodward’s suicide and ruined his own relationships with other society women around whom Capote had built his entire social infrastructure.

While Montillo’s research on Capote often relies on Gerald Clark’s definitive biography, Capote, few books have attempted a deep dive into the Woodward case itself. It’s often presented as tangential gossip circling around Capote’s larger story, but the noir elements hold up in book-length form.

Deliberate Cruelty captures a multi-branched narrative of true crime and gossip and scandal, a literary history, noir mystery, and tragic denouement. In the details and research of 1935’s grime, 1955’s glamour, and the decadence of 1975, Montillo examines distant shames. The modern value, however, is how past events reveal the grasping desperation behind how we have lived and still live today.

Capote used Woodward’s story as a narrative plot point in his notorious short story “La Côte Basque, 1965.” The story’s structure could be a shooting script for most meals shared by the gossipy women of the Real Housewives franchises. The cruel narrators of “La Côte Basque, 1965” dissect “Ann Hopkins,” Ann Woodward’s fictional stand-in, over lunch. They backstab their friends and associates, just as the Real Housewives use lunches to judge, critique, criticize, mock, and deride their closest friends from afar—after all, gossip’s point is that the targets can’t defend themselves.

Unlike some of the Real Housewives, Woodward stayed out of jail; like some of the Real Housewives, she faced exile for her deeds. A maybe-murderess was too notorious for Manhattan lunches and Long Island parties. In Europe, on a tight financial leash, she could enjoy dalliances with men like Claus von Bülow, decades before he became a scandal of his own.

It was at a 1956 dinner with von Bülow in St. Moritz, Switzerland, that she encountered Truman Capote. He was familiar with the Woodward family from his own climb up society’s long ladder. He had published Other Voices, Other Rooms in 1948, and gained sway among the wealthy of New York City.

“I read about her in an article about Capote along the way,” Montillo told The Daily Beast. “He was having dinner and she was there with [von Bülow] so soon after she had killed her husband. He wasn’t so much scandalized, as amused.”

Montillo writes, “At a certain point [Capote] was compelled to get up from his table and walk toward Woodward. He must have had a suspicion that the encounter would annoy her, which likely increased his delight at his own mischief.”

Woodward knew she was still a subject of stateside gossip. She knew Capote was part of the circle that made her a favorite target. She was not happy to see him.

“A short conversation followed, during which apparently, Ann called Truman ‘a little fag.’ He returned the slur by wagging his finger at her and calling her ‘Mrs. Bang Bang,’ a moniker that would stick to her for the rest of her days,” Montillo writes.

Capote’s cut-down has much more edge than Bethenny Frankel’s “Mention it all!” or Kandi Burruss’ “The lies! The lies!” but it’s all part of the same cultural DNA.

In a well-recounted quote where Capote faced a betrayal by one of his final friends, Lee Radziwill, mother-in-law to future Real Housewife Carole, he said “A southern fag is meaner than the meanest rattler. We just can’t keep our mouths shut.”

That mindset applied to his vendetta against Woodward. He intended to use her life’s catastrophe in his intended tour de force of Answered Prayers. He would describe this project as a sprawling epic that he promised would reveal all aspects of New York society. In the original conception, the case of Ann Woodward’s murderous social climbing was meant to drive the narrative.

Woodward and Capote had both driven themselves to heights far above their birth station. It is a shame that two such similar figures would then loathe each other—although it was not a fair fight. Woodward never fit in the world she craved. After her husband’s death, she accessed the estate’s money only because her mother-in-law wanted to protect her family name. Her exile to Europe ensured only one Mrs. Woodward remained in New York City. She had no influence. Capote targeted far below his weight class, but he did it even so.

“These types of social climbers don’t like themselves. They would remind each other too much of each other,” Montillo speculated. “They’re looking to start different lives away from the places they came from. Once they reached some status they thought was appealing or good, what would [Capote and Woodward] gain from being reminded of their background?”

Capote was happy to talk about his background and most aspects of his youth in Alabama’s poverty, but on his own terms, to build his own brand. Woodward’s brand crashed down into murder and Capote’s dinner table mockery.

Capote didn’t have a chance to speak before Ann jumped from her seat to confront him, Montillo writes—would he have been kind? Or curious, even politely disingenuous? Was his interest in causing more hurt?

It’s fair to say that her reflexive anger, before Capote established his intent, was jealousy; Capote still thrived in the same world she attained before it threw her over.

Like the youthful Capote escaping Alabama, Woodward rose from a mother disappointed in her own life. Her mother Ethel wanted to be a teacher but ended up a divorcee running a taxi service in Kansas City. It was like Ann’s movie star idol Joan Crawford’s real-life childhood of poverty, and Crawford’s later role in Mildred Pierce, mother to an ungrateful daughter hustling her way to better things.

“By the time [Ann] was 22, her curves had filled out and so had her seductive manners. Ann walked around the taxi office as if sauntering down a fashion runway,” Montillo writes. “She reacted to men’s jokes even when she didn’t need to. But she was just practicing, Ann told Ethel with a twinkle in her eye; though for what, she never explained.”

She had been tested in her youth, with an IQ of 131. “She was a very smart girl. She says it in passing, but she was near-genius level,” Montillo said. “She kind of glosses over that.”

From Kansas City, she escaped to New York and a job as a taxi dancer at a club. Montillo reveals that she even had an All About Eve moment, having an affair with her idol Joan Crawford’s estranged husband, actor Franchot Tone.

She had first dallied with William Woodward’s father, before he passed her to his son, who he feared was homosexual, with the idea that “she rid Billy of his virginity.” From there, it led to a young man’s rebellion against his parent’s expectations, an abusive marriage, mutual affairs, deceit and discovery.

The fictional “La Côte Basque, 1965,” presents Ann Woodward as a secondary character, Ann Hopkins, shocked to action when her husband, “asked her for a divorce; it appeared that her first marriage hadn’t been annulled. Rather, she was still married to her first lover and had engaged in a bigamous relationship with the second.”

Ann and William Woodward Jr.

Bettmann/GettyAs Capote wrote: “[Ann] decided to kill him: a decision made by her genes, the inescapable white-trash slut inside her.”

The story was full of slurs like that, told by the upper crust. The story’s narrator, “Jonesy,” a striver in the Capote mold, shared lunch with Lady Ina Coolbirth, a stand-in for Capote’s best friend, Nancy “Slim” Keith. The two eviscerated their shared circles, telling tales that while vague to most of Esquire’s readers, were black-and-white revelations to those in the know.

The real-life Ann Woodward was not quite as scandalous as the Ann Hopkins version, but Woodward had been previously married, had pretended her living father was dead, had carried on at least one affair, and had kept her mother’s own multiple relationships hidden—these were all very divorceable scandals in her era, if not as much today’s. Divorce and losing custody of her two children would have left her with nothing.

As her husband cold-bloodedly told her once he had uncovered her secrets, “it was high time that she returned to Kansas.”

All the effort of a smart girl to learn how to fold napkins, wear dresses below the knee, to behave and fit into a world far from the desolation of Pittsburg, Kansas, would all have been for nothing.

“Manipulating a persona, creating this persona of being a socialite who belongs, it takes an enormous amount of planning,” Montillo said. “Not really that hard to think that she could also plan a murder.”

The shooting itself is not especially interesting. But in police records and court transcripts, it becomes clear that whatever happened on the early morning of Oct. 30, 1955, it was more important for the Woodward family to call it an accident. If Ann got away with murder, that was a fair trade for the family name to avoid that scandal.

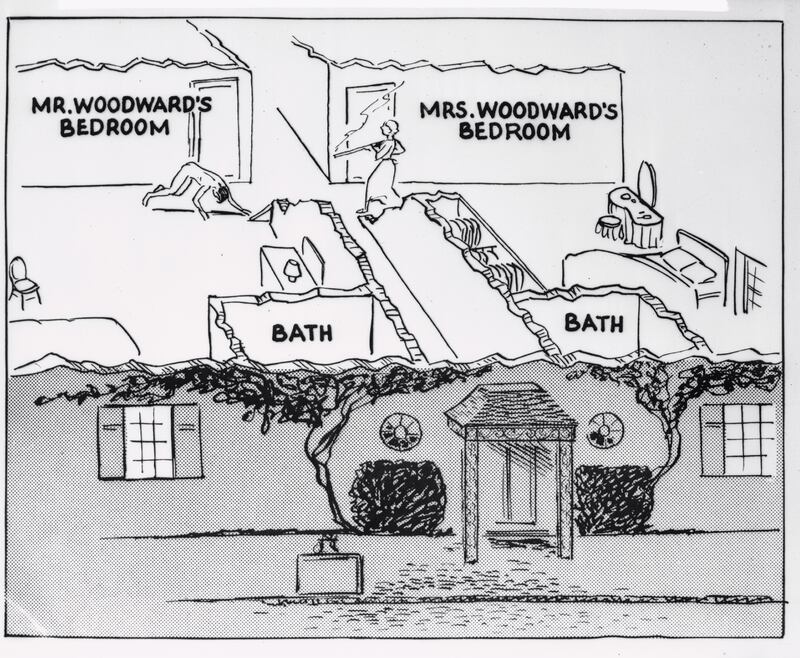

A sketch by World-Telegram and Sun artist Bill Pause showing, according to the police report, where Mrs. William Woodward Jr. stood in her bedroom and fired the fatal gunshot blasts into her husband

Bettmann/GettyWhen Capote’s “La Côte Basque, 1965” dredged it up again, it might have killed Ann Woodward, emotionally unable to revisit her notoriety. It certainly shocked Capote’s friends like Slim Keith, or Babe Paley—who saw themselves portrayed as malicious, shrewish gossips revealing the worst about each other. Just as Ann Woodward was canceled by her culture in 1955, Capote faced the same wrath: party invitations stopped coming, lunch dates faded away. Even Capote’s lesser hangers-on shunned him, like real estate investor Jerry Zipkin, who demanded that his table be moved away from where Capote sat with his biographer Gerald Clarke.

“Truman is ruined,” Zipkin told columnist Liz Smith. “Those who receive him will no longer be received.”

In the piece, Smith put Zipkin in his place, referring to him as “society’s favorite extra man.” Still, on that day, he was on the top rail.

At the time, Capote laughed it all off—shocked, shocked! he was by the reception, telling anyone who listened that he was a writer, and what did they expect. In private he was not as happy.

Capote defended his story to Liz Smith in a 1976 piece in New York magazine.

Smith wrote, “I remind him that nobody can really judge a literary work for 50 years.”

“This won’t even be dated in 50 years!” Capote told her.

Capote was right. The style is dated, of course, and today’s fictional stories are unlikely to generate cultural impact. But just under 50 years from publication, we witness a real-life version of “La Côte Basque, 1965” all the time. Ann Woodward has been dead these many years, but Bravo TV and Andy Cohen bring her spiritual daughters to life each day of the week.

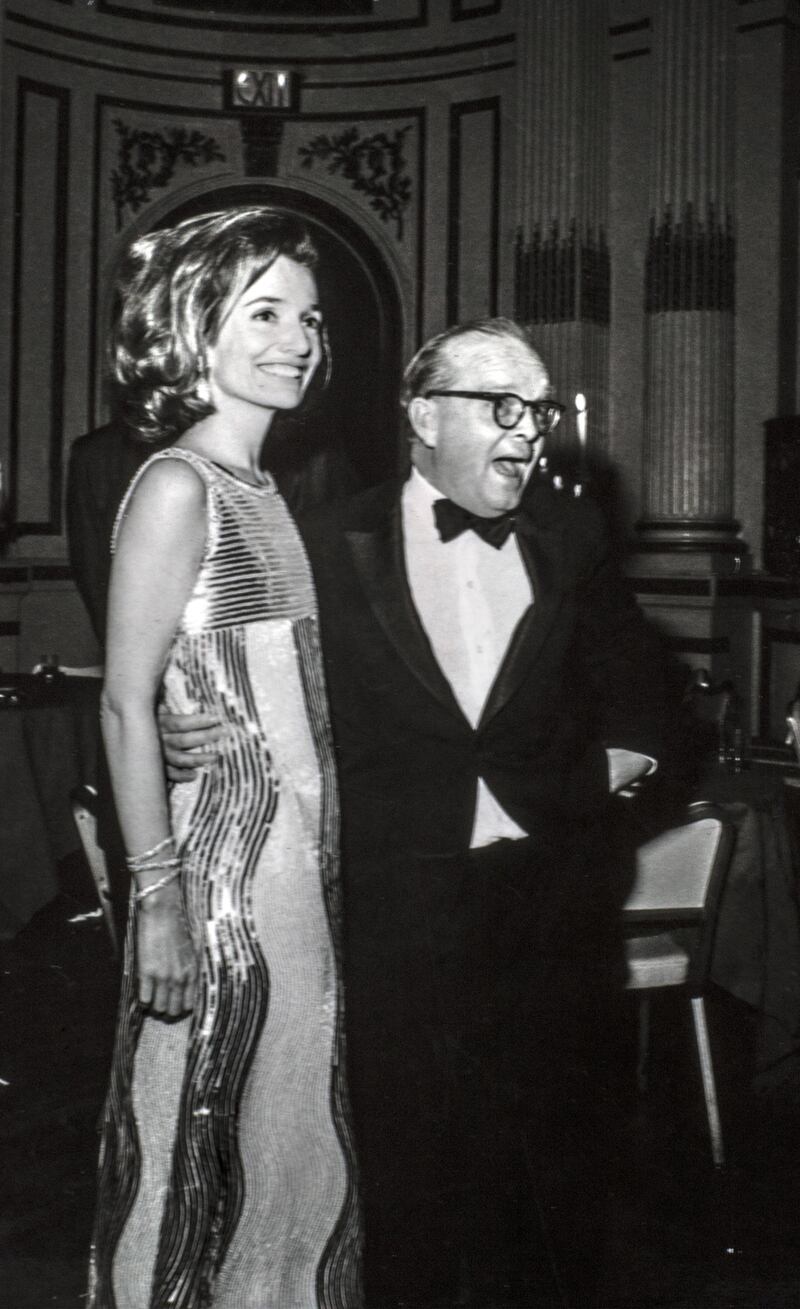

Lee Radziwill dancing with Truman Capote at Truman Capote BW Ball on Nov. 28, 1966, in New York

Santi Visalli/GettyThe 1975 socialites Babe Paley, Slim Keith, and Lee Radziwill find their contemporary doubles in Carole Radziwill, Kandi Burruss, and Lisa Vanderpump. The scandal of Ann Woodward becomes Erika Jayne or Jen Shah or Teresa Giudice. Woodward’s suicide, brought on by the fear of renewed exposure and shame, mirrors Russell Armstrong’s 2011 suicide in the wake of a variety of accusations.

The Real Housewives franchises present that same world of social climbing and it’s easy to tell who belongs and who doesn’t. Hotel heir Kathy Hilton can show up in puffy slippers because she doesn’t need to care, while Lisa Rinna is always a slip away from rebecoming the soap opera poser ever short of a real breakthrough.

One thing missing from the Real Housewives is a Capote figure. There’s no literary equal willing to participate in the cinematic universe of Andy Cohen and Watch What Happens Live, but then in 2022 there’s no literary equal to the way Capote utilized his celebrity.

Ann Woodward killed herself on Oct. 10, 1975, and the story of her death appeared in most newspapers on Oct. 13. Capote was on a university speaking tour, and had appeared that month in such disparate locations as Redding, California and Albuquerque, New Mexico.

On Oct. 19, he was in Kansas, Woodward’s home state, and site of the Clutter murders and the inspiration for In Cold Blood, Capote’s greatest triumph. He had begun to hear rumbles that “La Côte Basque, 1965” had not been well received. Earlier that month, he foreshadowed the drama to columnist Joyce Haber, telling her, “We’ll have to see what the fallout will be like.”

At the University of Kansas, Capote told the 3,000 attendees that his forthcoming Answered Prayers would use some real names and be the subject of a little notoriety.

“Why not use their names? There’s nothing in the book that isn’t true. Why not write a novel and use this logical extension of the journalistic concept?” Capote said. “Everybody was quite shocked. In the next few weeks, we’ll see if I get tossed in jail. If people want to sue me, well, we’ll see.”

Shocked enough for suicide? Jail for abetting the action? Did he know about Woodward’s death? Was he worried? Or was it just a throwaway line to amuse the college kids?

On the 20th anniversary of William Woodward Jr.’s death, Oct. 29, 1975, Capote appeared on The Tonight Show, a precursor to talk shows like Andy Cohen and Watch What Happens Live. Cohen and Johnny Carson share a style of unflappable cool, though Carson is more willing to let the guest hold the stage.

It’s interesting, watching Capote hold court for 15 minutes when his stories lack a point, or anything to sell. Capote was in Los Angeles shooting his role in the comedy Murder by Death.

Just a few hundred miles north that same day, Gloria Vanderbilt was in San Francisco and was asked by a San Francisco Examiner reporter about “La Côte Basque, 1965.”

“I have not seen Truman Capote’s story, nor do I intend to,” she said, no doubt with a billionaire’s iciness. Never mind that Capote had just blurbed her husband Wyatt Cooper’s recent book, never mind their long friendship.

Vanderbilt-Cooper, the mother of Andy Cohen’s good friend Anderson, is in “La Côte Basque” by name—not recognizing her first husband when he says hello; relating a story about a friend of J.D. Salinger who died in the New Hampshire woods, “wrapped in a blanket and holding an empty whiskey bottle”; saying about a friend’s social event, it was “marvelous. If you’ve never been to a party before.”

During Capote’s Tonight Show appearance, Carson directs the conversation to Capote’s new book, as though its release is imminent—“your first major thing since In Cold Blood, isn’t that right?” Carson asks.

“This book is called Answered Prayers; I have a long chapter from it in Esquire. I plan to publish not the whole book that way but five or six sections. After that I’ll publish the book in its entirety, it’s very long, 700 or something pages.”

They don’t talk about the brewing scandal, or Ann Woodward, or the fact that Johnny Carson is also a character in “La Côte Basque, 1965”—Bobby Baxter, a womanizing comedian with a mistress who calls Baxter’s wife to make fun of her. The quick-thinking Jane Baxter, a stand-in for Capote’s friend Joanne Carson, tells her, “I’ve got a double dose of syph and clap, all courtesy of that great comic, my husband, Bobby Baxter—and if you don’t want the same I suggest you get the hell out of there. And she hung up.”

Truman Capote and Barbara Walters on The Tonight Show

NBC/GettyCapote was on The Tonight Show 19 times from 1968 to 1975, usually twice a year. After “La Côte Basque’s” publication, he appeared once more, when Barbara Walters was the guest host. Just as NeNe Leakes seems to be persona non grata to Andy Cohen, Capote never again appeared with the notoriously grudgeful Johnny Carson.

Then the drugs, the booze, the partying. From 1975 to his 1984 death, there was a book of short fiction and some essays. Answered Prayers appeared posthumously in 1986, not as 700 pages but just 180 pages.

If Capote published “La Côte Basque, 1965” in 2022, there would be no similar blacklisting—today’s society figures would crave Capote’s attention, thirsty for the flavor of his juicy portrayals. Now and then the words would reveal how someone went to Emergency, or someone went to jail, and someone might be bitter. Cost of doing business. It was different in October 1975.

“It’s part of why I was attracted to both of them,” Woodward and Capote, Montillo said. “They were both bound to fail, and the failure will be massive and public and catastrophic.”