For $3 a day, Yesica works the graveyard shift in the kitchens of the for-profit immigration prison where she is locked up.

Each morning, at 1 a.m., the guards of the Joe Corley Detention Facility in southeast Texas rouse Yesica and the 35 other women who share a dormitory-style room. Work begins an hour later and lasts through sunrise, ending at 8 a.m. Yesica does everything from cooking breakfast, to serving her fellow detainees, to cleaning up.

Even at $3, toiling in the kitchen pays better than sweeping prison corridors, which pays the Immigration and Customs Enforcement-stipulated minimum of $1 a day. The work, officially speaking, isn’t mandatory. But “since there’s absolutely nothing to do” inside, Yesica said, detainees work to keep at bay the stress of not knowing when they’ll be released—or if they’ll be deported.

Yesica, 23, fled her native El Salvador after MS-13 persecuted her for being a lesbian. The brutal gang, which the Trump administration uses to demonize immigrants like her, murdered her father, and she came to the United States to seek the safety of rejoining family here. She has instead spent the last two years locked inside ICE’s prisons.

“This is a really terrible place,” Yesica told The Daily Beast through a translator from the Corley center. “It’s inhumane. It’s like a torture chamber.”

These are dangerous times for undocumented immigrants. ICE has been super-charged by the Trump administration. And ICE’s empowerment has been lucrative for the companies that both cage and employ immigrants like Yesica.

A Daily Beast investigation found that in 2018 alone, for-profit immigration detention was a nearly $1 billion industry underwritten by taxpayers and beset by problems that include suicide, minimal oversight, and what immigration advocates say uncomfortably resembles slave labor.

Being in the U.S. illegally is a misdemeanor offense, and immigration detention is technically a civil matter, not a criminal process. But the reality looks much different. The Daily Beast reported last month that as of Oct. 20, ICE was detaining an average of 44,631 people every day, an all-time high. Now ICE has told The Daily Beast that its latest detention numbers are even higher: 44,892 people as of Dec. 8. Its budget request for the current fiscal year anticipates detaining 52,000 people daily.

Expanding the number of immigrants rounded up into jails isn’t just policy; it’s big business. Yesica’s employer and jailer, the private prisons giant GEO Group, expects its earnings to grow to $2.3 billion this year. Like other private prison companies, it made large donations to President Trump’s campaign and inaugural.

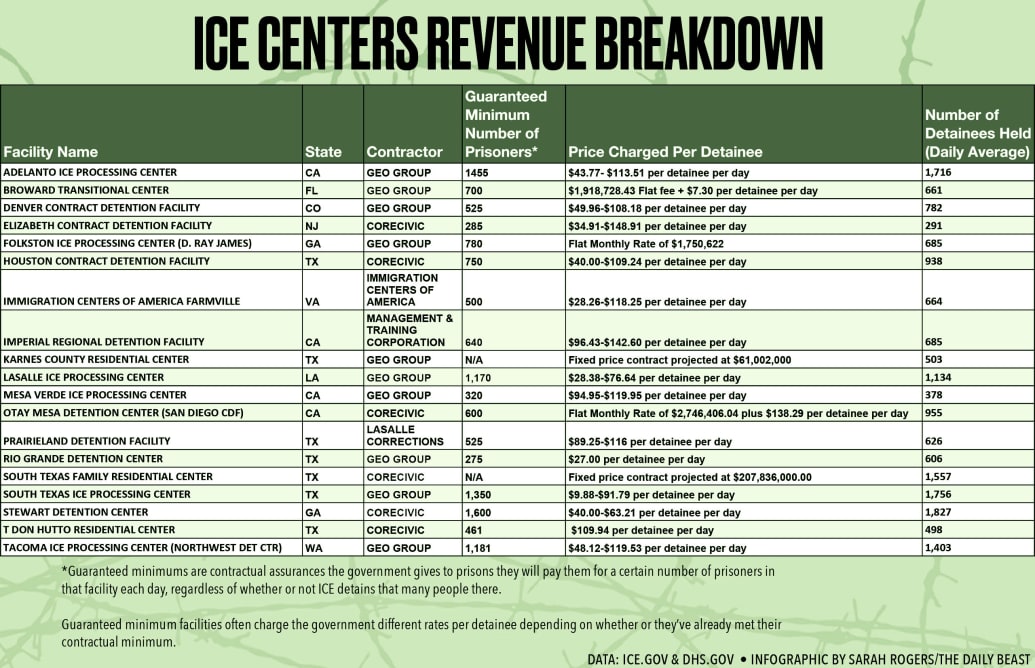

Pinning down the size and scope of the immigration prison industry is obscured by government secrecy. But the Daily Beast combed through ICE budget submissions and other public records to compile as comprehensive a list as possible of what for-profit prisons charge taxpayers to lock up a growing population, and how many people those facilities detain on average. The result: For 19 privately owned or operated detention centers for which The Daily Beast could find recent pricing data, ICE paid an estimated $807 million in fiscal year 2018.

Those 19 prisons hold 18,000 people—meaning that for-profit prisons currently lock up about 41 percent of the 44,000 people detained by ICE. But that’s not a comprehensive total, and the true figures are likely significantly higher. The National Immigrant Justice Center estimated that for November 2017, roughly 71 percent of immigrant detainees, then a smaller total figure, were held in 33 privately operated jails like the Joe Corley detention center in Texas where Yesica resides.

Providing a comprehensive tally of ICE detention centers is difficult. The Department of Homeland Security claims ICE operates “nearly 250,” but a study earlier this month for the American Immigration Council found 638 sites, more than twice the DHS figure. ICE told The Daily Beast it uses 205 facilities, citing information on its website that immigration researchers consider incomplete and misleading. Separating out the privately run facilities is even more difficult, since some of ICE’s state and local partnership prisons are run by for-profit companies, and complete lists are frustratingly difficult to find. In response to The Daily Beast’s queries, ICE said it could not provide a full breakdown of contractor-operated immigration prisons.

“Ensuring there are sufficient beds available to meet the current demand for detention space is crucial to the success of ICE’s overall mission. Accordingly, the agency is continually reviewing its detention requirements and exploring options that will afford ICE the operational flexibility needed to house the full range of detainees in the agency’s custody,” said ICE spokesperson Danielle Bennett.

But Mary Small of the Detention Watch Network says the public still lacks “incredibly basic information about immigration detention and how private prison companies are profiting from it.”

“Even though billions of taxpayer dollars are being obligated to private prison companies, the contracts between them and the federal government aren't publicly available, so we don't know how much these companies are being paid, how many people they're holding or how long their contracts last,” Small said. “This culture of secrecy—bolstered by revolving door politics and political contributions—have paved the way for a rapid and reckless expansion of the detention system.”

GEO Group, which owns the Corley center, is just one example. It held a daily average of 973 people in the previous fiscal year at Corley. Beyond Corley, it detained roughly 11,000 immigrants at 17 prisons. The 10 GEO Group facilities The Daily Beast could find pricing data for charged an average of about $101 per prisoner per day, compared to ICE’s overall projected $121.90 average daily rate for adult beds in fiscal year 2018. But the Government Accountability Office warned in April that ICE consistently lowballs its detention costs through dubious accounting.

GEO Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Photo illustration by Sarah Rogers/The Daily Beast

While for-profit immigration detention by no means began on Trump’s watch, the Trump administration has been very good for the corporation. In November, GEO Group reported that it expects to earn $2.3 billion this year, including immigration detention revenues—an increase of nearly 1.8 percent from the $2.26 billion it reported in 2017 and up 5.5 percent from the $2.18 billion it earned in 2016—the year it began imprisoning Yesica. That same year, GEO gave $281,360 to Trump’s campaign.

In 2004, GEO Group spent $120,000 on federal lobbying. By 2016, it was spending $1.2 million. Fellow private prisons giant CoreCivic spent nearly $10 million between 2008 and 2014 just to lobby the House appropriations subcommittee that controls immigration-detention funding. Together, according to the Migration Policy Institute, the two corporations dished out a combined half-million dollars to Trump’s inauguration committee.

In essence, immigration advocates say, the detention corporations pay Trump and his congressional allies, whose enthusiasm for treating immigration as a crime ensures delivery of a growing population of captives to companies that pay them far below a minimum wage.

ICE’s internal detention standards set pay for “voluntary” immigrant labor at only “at least $1.00 (USD) per day.” (“The negative impact of confinement shall be reduced through decreased idleness, improved morale and fewer disciplinary incidents,” ICE contends, even though immigration detention is supposed to be administrative, not punitive.)

Lawsuits over the past few years present an alarming accumulation of accounts that labor within the private prisons is less “voluntary” than the corporations insist. A class-action lawsuit against GEO Group, initially by nine detainees in Colorado, claims that tens of thousands of immigrants have been forced to work for their $1 daily wage. A different lawsuit against a GEO Group facility in California claims “systematic and unlawful wage theft, unjust enrichment, and forced labor,” including a scheme in which the corporation requires work to “buy the basic necessities—including food, water, and hygiene products—that GEO refuses to provide for them.” Washington State sued GEO Group in 2017 for paying its detainees $1 a day—or sometimes in what the complaint calls “snack food”—rather than the $11/hour state minimum wage. GEO Group has vigorously contested the suits, though not always successfully.

“To the extent that the industry is in the business of expanding the system so they can make more money off holding more immigrants that can be confined, and doing everything possible to profit off of it by labor processes like getting detainees to work and paying them a dollar a day, there is very little distinction you can draw between slave labor and what they’re doing,” said Emily Ryo, an associate professor at the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law.

The differences between for-profit immigration prisons and public immigration prisons are substantial, according to recent research by Ryo and colleagues based on data from fiscal year 2015. Even though for-profit companies operate only an estimated 10 percent of ICE detention facilities, both Ryo and the National Immigrant Justice Center found that more than two-thirds of all detainees have been held at least once at a privately run prison. Those for-profit prisons “consistently and substantially” hold immigrants longer than public ones—about 87 days on average for people ultimately granted relief, versus 33.3 days in public prisons.

Fifteen of the 179 detainees who died in ICE custody between October 2003 and February 2018 were held at a single private immigration detention center, run by CoreCivic in Arizona, according to the Migration Policy Institute. At another privately run immigration detention jail, GEO Group’s Adelanto ICE Processing Center in California, there have been seven suicide attempts between December 2016 and October 2017, and at least one success. A September DHS inspector general’s report showed photographs of bedsheets hanging as improvised nooses inside Adelanto cells. A detainee told inspectors, “I’ve seen a few attempted suicides using braided sheets by the vents and then the guards laugh at them and call them ‘suicide failures’ once they are back from medical.” Another detainee death classified as a suicide occurred at CoreCivic’s Stewart Detention Facility in July 2018, also using a bedsheet noose.

And ICE turns what its own watchdog warns is a blind eye to detention conditions. It even contracts out substantial amounts of oversight over its detention centers. A June report by the DHS inspector general found that the inspections contractor, Nakamoto, uses practices that “are not consistently thorough,” and its inspections don’t “fully examine actual conditions or identify all compliance deficiencies.” While ICE’s additional in-house inspectors are more thorough—they found 475 deficiencies at the same 29 detention sites where Nakamoto found only 209—the inspector general found those inspections “too infrequent to ensure the facilities implement all corrections.” The result, the inspector general says, is that ICE doesn’t “ensure adequate oversight or systemic improvements in detention conditions.”

Laura Lunn, an attorney with the Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network in Colorado, observes the system up close. At the private prison in Aurora where Lunn provides legal services–the prison that sparked one of the class action suits against GEO Group–she can wait 90 minutes to see clients. She gets walked through a metal detector and wanded as if she’s there to deliver nail files and shanks instead of advice. Her team of six attorneys comprise the sole nonprofit legal provider for almost 1,000 people.

Lunn said that one depressed client can “articulate what medicines she requires,” but the prison gave her a different prescription that worked poorly. Another client, she said, was able to walk when he got to the Aurora ICE Processing Center but is now in a wheelchair. “I think it’s very inappropriate for someone in that situation to be detained,” Lunn said.

Yesica has representation in Corley, for all the good that it does her. She can’t recall how many times she’s been before a judge as she attempts to apply for asylum and appeal a denial. But she does know that she hasn’t seen one in the seven months that account for her most recent stay in Corley.

Life at Corley is “very stressful,” said Yesica, who also told aspects of her story to the Houston Chronicle last year. She lives as one of 36 women in a room secured behind a heavy door locked through an electronic code. The women share two sinks and two toilets.

Yesica spends the vast majority of her time in the dormitory. Detainees leave only when a guard takes them to see their lawyers, their visitors, or to work. Some choose to work for GEO Group’s paltry wages to break up the monotony. Recreation time comes once a week in a different room.

“They give us a ball to play soccer or whatever. We don’t go outside. I don’t breathe fresh air, haven’t been outside since I’ve been in here,” she said.

While the Trump administration has used the specter of MS-13 to rally support for its draconian immigration policies, Yesica has actually experienced the gang’s brutal violence.

Yesica’s sexual identity made her a target in her native El Salvador. She recounted being attacked in San Salvador and San Vicente. In 2016, her father began walking her to and from school to protect her from the gang members who had taken to following her. For that, she said, “my father was killed in the plaza in broad daylight by MS-13.”

After MS-13 murdered her father, it threatened her and her mother with the same fate. She, her mother, and two brothers fled in fear to the United States, where they had family. They took buses and trains and stayed in hotels until they reached Texas in August 2016.

But Yesica got separated from her family and promptly deported. She went back to to San Vicente, and stayed briefly with her aunt, uncle and grandmother. But then her uncle attacked her. “I came back to the U.S. in an emergency,” she said. “I wouldn’t have made such a trip or taken such risks unless I was running for my life.”

It was later in 2016—she doesn’t remember exactly when—when Yesica returned through Texas. It didn’t take long before immigration officials rounded her up. She said she was offered the choice of going with them or “they’d put me in jail for five years.”

The rooms were “freezing cold and you couldn’t wash” in her first detention facility. Three days later, she was taken to Corley. She spent nine months there, and then—like 60 percent of detained immigrants, according to Ryo’s research—she was transferred elsewhere. Seven months ago, she returned to Corley, located about 40 miles north of Houston.

“The whole system is exploitative,” said Lunn, the attorney in Colorado. “It takes away the humanity of the people it detains and tells them, you can’t be with your family, you can’t go outside, you have very little agency, and while you’re here, you’ve got to represent yourself in an immigration case without any tools, really, to succeed. The labor piece of their detention is a small fragment of the ways their dignity is stripped from them. It’s dehumanizing.”

When she’s not working and not seeing her attorney, Yesica spends her time on her bed in Corley. She reads, she listens to music or she watches TV. There are “some good people here,” she said vaguely, but mostly she guards herself and tries not to get involved. As the years pass, she waits to hear if she’ll be granted asylum, or sent back to the “very violent place” she fled.

“I was fleeing from the abuse and being threatened because of my sexual identity,” Yesica said. “I’ve gone through a lot and it’s been very difficult, but if I stayed in my country, I’d be dead.”