Bush's Defense secretary chides Colin Powell, says he would have gone into Iraq even if he'd known Saddam had no WMDs—and discusses his son's drug problem. Howard Kurtz speed-reads Rummy's new memoir. Plus, lighter anecdotes from Rumsfeld's memoir, including his unromantic proposal and his take on Hurricane Katrina.

Ten days after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Donald Rumsfeld wrote himself a note.

"At the right moment," it said, "we may want to give Saddam Hussein a way out for his family to live in comfort."

In his forthcoming book, Known and Unknown, the former Defense secretary says he believed that "an aggressive diplomatic effort, coupled by a threat of military force, just might convince Saddam and those around him to seek exile." Instead, history will record that Rumsfeld became a principal player in the Bush administration's drive to invade Iraq, which led to the execution of Saddam, the deaths of more than 4,400 American soldiers and a long, grinding war that will forever define his reputation.

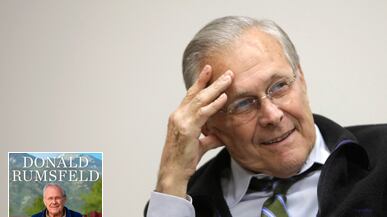

In Known and Unknown, which was purchased by a reporter at a Washington bookstore in advance of its official release, Rumsfeld offers a muscular, uncompromising defense of his tenure, the military operations he helped direct in Afghanistan and Iraq and the president he served. He settles his share of scores, most notably with Colin Powell, Condi Rice, Dick Armitage and the media. While he acknowledges some missteps along the way, Rumsfeld also chastises high-ranking Democrats and insists—as does George W. Bush—that even if he had known in 2003 that Saddam did not possess weapons of mass destruction, the former defense secretary would still have favored going to war.

One of the few personal anecdotes in the 815-page volume takes place more than 12 hours after hijacked planes struck not only the World Trade Center but the Pentagon, filling his office with heavy smoke and forcing him to evacuate with other employees, some of them wounded. His spokeswoman, Torie Clarke, asked if he had called his wife of 47 years, Joyce. Rumsfeld replied that he had not.

"You son of a bitch," Clarke said with a hard stare.

"She had a point," Rumsfeld writes.

The book, which also recounts his first tour as Pentagon chief under Gerald Ford, begins with Rumsfeld's 1983 trip to Baghdad as Ronald Reagan's envoy. "It seems unnatural," Saddam told him during a two-hour meeting, "to have a whole generation of Iraqis growing up knowing little about America and a whole generation of Americans growing up knowing little about Iraq." Rumsfeld had uttered the same words the night before to the Iraqi dictator's aide, Tariq Aziz, and wondered whether the room had been bugged.

Nearly two decades later, in the rubble of 9/11, Rumsfeld took grim note when Saddam gloated that "the United States reaps the thorns its rulers have planted in the world."

But first there was Afghanistan, which had harbored bin Laden. Rumsfeld pushed the CENTCOM commander, Tommy Franks, for a quick war plan, brushing aside the general's insistence that he needed two months to devise one. Critics might question why the United States didn't immediately prepare to deploy as many as 150,000 troops to Afghanistan, Rumsfeld writes. But "we would have needed many months to build a large occupying army," and "this would have given the Taliban time to prepare for the conflict, and al Qaeda both the incentive and the opportunity to relocate."

"The president did not lie. The vice president did not lie. Tenet did not lie. Rice did not lie. I did not lie. The Congress did not lie. The far less dramatic truth is that we were wrong," Rumsfeld writes.

Once the Taliban were toppled, Rumsfeld emerged as a major media personality, mocked by Darrell Hammond on Saturday Night Live, to his amusement. "If one starts with 'good press,' one often gets more and more favorable coverage; early bad stories often spawn additional negative reporting," he says. "But journalists also relish dramatic reversals." That was yet to come.

Rumsfeld devotes little space to the fiasco at Tora Bora, saying he told CIA Director George Tenet in a memo that "we might be missing an opportunity" there and should perhaps bring in more U.S. forces.

He says he later learned that a CIA operative on the ground had requested that some Rangers be sent, but "I never received such a request from either Franks or Tenet and cannot imagine denying it if I had. If someone thought bin Laden was cornered, as later claimed, I found it surprising that Tenet had never called me to urge Franks to support their operation." Perhaps, he says without elaboration, "their recollections may be imperfect."

Rumsfeld takes a similar tack on a question that came to haunt the Bush administration: Why didn't the Pentagon dispatch more troops to Iraq at the outset, rather than Rumsfeld's preferred option of a light and agile force? "There was no disagreement among those of us responsible for the planning," Rumsfeld says, adding: "If anyone suggested to Franks or [Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Richard] Myers that the war plan lacked sufficient troops, they never informed me." It was as though that ended the debate, when subsequent events made clear that the decision not to send more troops allowed Iraq to descend into bloody turmoil that would drag on for years.

In the months leading up to 9/11, Rumsfeld says, he had to deal with a serious distraction: His son, Nick, who had been battling drug addiction, had relapsed, and would disappear for periods of time. After the attacks, he choked up in a meeting with Bush while thinking of his son.

On Nov. 21, 2001, the president led Rumsfeld to a small office near the Situation Room and asked: "Where do we stand on the Iraq planning?" Rumsfeld quickly prodded military leaders on the subject. It's the latest confirmation that war—or at least serious war planning—was gearing up long before the public was clued in, and despite the absence of any link between Saddam and the terrorist attacks.

The book retraces familiar ground—the U.S. intelligence estimates in 2002 that Saddam had chemical and biological weapons—with Rumsfeld arguing that "recent history is abundant with examples of flawed intelligence that have affected key national security decisions and contingency planning." This, of course, was the mother of all intelligence failures, but Rumsfeld attempts to shift the argument to higher ground, saying illegal weapons "should have been only one of the many reasons" for invading Iraq, including violations of U.N. resolutions and attacks on American pilots in the no-fly zone. But it was WMD, of course, that was the principal tool in the administration's salesmanship of the war.

In fact, he challenges those who charged that "Bush lied, people died," saying critics had "scoured a voluminous record of official statements on Iraqi WMD to compile a small string of comments—ill chosen or otherwise deficient—to try to depict the administration as purposefully misrepresenting the intelligence."

Rumsfeld acknowledges having made one "misstatement," early in the war, involving the CIA's designation of various "suspect" WMD sites in Iraq. "We know where they are. They're in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad," he said. Rumsfeld says he should have used the phrase "suspect sites."

The author doesn't just play defense. He resurrects quotes from Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, John Kerry and Al Gore as supporting the WMD allegations—and the war. "Yet when opposing the Bush administration's efforts in Iraq became politically convenient," says Rumsfeld, "they acted as if they had never said any such thing."

Rumsfeld takes direct aim at Colin Powell in recounting the former general's famous U.N. speech in February 2003, laying out the administration's case that Saddam indeed possessed a stockpile of banned weapons. "Over time a narrative developed that Powell was somehow innocently misled into making a false declaration to the Security Council and the world," Rumsfeld writes. He seems particularly offended that Powell has said that some in the intelligence community knew "that some of these sources were not good," "didn't speak up," and "that devastated me."

Rumsfeld fires back that the secretary of State had once been "the most senior military officer in our country" and no one else in the administration had "even a fraction of his experience" on intelligence matters. "Powell was not duped or misled by anybody, nor did he lie about Saddam's suspected WMD stockpiles. The president did not lie. The vice president did not lie. Tenet did not lie. Rice did not lie. I did not lie. The Congress did not lie. The far less dramatic truth is that we were wrong."

Rumsfeld also takes a swipe at his Marine Corps commandant, Gen. James Jones, and Army chief, Gen. Eric Shinseki, who were cited in a December, 2002 Washington Post story as opposing an invasion of Iraq. Jones told him it wouldn't happen again; Shinseki said he had not expressed doubts to anyone: "Who do you believe? The Washington Post or me?" Rumsfeld complains that he "cannot explain their failure to correct the public record." (Rumsfeld also denounces the widespread press accounts that Shinseki was forced to retire early for testifying shortly before the war began that "several hundred thousand soldiers" would be needed. "This hardened into a myth that he was punished for telling the truth about the war," the author writes.)

One by one, Rumsfeld takes on lingering controversies from the war effort and often assigns blame elsewhere. The looting of an Iraqi museum, which became a worldwide symbol of a lack of order? The media reports were way overblown, and "the news stories tended not to blame the Iraqi fighters for breaking into the museum, turning it into a combat zone, and putting its collections at risk."

But he confesses to "a few ill-chosen words" at a subsequent press briefing—a time, says Rumsfeld, when he was under additional strain because his wife was in the hospital with a ruptured appendix. "Think what's happened in our cities when we've had riots, and problems, and looting. Stuff happens!" he told reporters.

But he adds that media outlets "who created and spread the grossly false and harmful stories about the museum looting took no responsibility," as if they had collectively shrugged, "stuff happens."

Rumsfeld seems to suggest it was a mistake for American civilians to be running Iraq—he offered to go there for two weeks—rather than "putting an Iraqi face on postwar Iraq as soon as possible." But he noted that Powell's State Department had "proposed an American-led civil authority for an indefinite period."

As for Bush's "Mission Accomplished" appearance on the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln, well, Rumsfeld says, the president's "public affairs team" did not appreciate that the end of major combat operations was hardly the end of the mission. He had seen an early draft of Bush's "too optimistic" speech for that day and, over the phone, "suggested edits to tone down any triumphalist rhetoric." But the phrase on the aircraft carrier banner, Rumsfeld said, "would haunt his presidency until the day it ended."

Another Rumsfeld nemesis, as painted in these pages, was Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage. "His leaks were so brazen," Rumsfeld writes, that he told Powell to manage his deputy: "Rich Armitage has been badmouthing the Pentagon all over town. It's been going on for some time and it's only gotten worse…I don't know what the hell is in Armitage's craw, but I'm tired of it."

Powell, in turn, expressed concern that Rumsfeld's deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, "was leaking against him"—which Rumsfeld says he did not believe. You might describe this as the war behind the war.

The sniping reached the Oval Office. "It needs to stop," Bush told him. Rumsfeld responded that it was State that was trashing the Pentagon. Chief of staff Andy Card said he heard the opposite complaint from Powell's team.

Bush called the next day. Rumsfeld recalls telling him that "what is happening is hurting you. If it gets to a point where the solution is for me to leave, I will do so in a second."

"That's a crappy solution," Bush said. He said he had seen the recent articles and was "working hard on Powell and Armitage."

Another Rumsfeld culprit is Paul Bremer, the civilian administrator in Iraq, who is portrayed as an ambitious man who seemed to convey the sense that America was an occupying power. Bremer's decision to disband the Iraqi army flooded the streets with angry, jobless young men, some of whom would later join the insurgency. But "in truth," Rumsfeld writes, "it wasn't all Bremer's fault…I was told of Bremer's decision and possibly could have stopped it."

And there was a major clash with Condoleezza Rice, Bush's national security adviser. News stories in late 2003 portrayed Bush as handing Rice the power to manage postwar Iraq, but, Rumsfeld writes, she reversed herself and told the press that nothing about the administration's Iraq policy had changed.

A week later, says Rumsfeld, Rice privately apologized for the flap.

"You're failing," he recalls telling her. "You could have said something in the NSC meeting in front of the president and the principals."

"Don, you've made mistakes in your long career," Rice replied.

"Yes, but I've tried to clean them up."

There were glimmers of good news. When the fugitive leader who Rumsfeld had once met in Baghdad was captured, Rumsfeld thought it would be "tempting for me to meet with Saddam in jail," but then ultimately decided against the trip.

But the war effort was not going well. Rumsfeld was appalled by the photos of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison, but says the public might have viewed them as evidence of a small group of guards run amok if other pictures had been released—"showing soldiers engaged in similarly disturbing sexual, sadistic acts—but with each other: Americans on Americans."

A week later, Rumsfeld gave the president a handwritten note saying "that you have my resignation as Secretary of Defense any time you feel it would be helpful to you."

"Don, someone's head has to roll over this," Bush told him. But the president called him that night and said that "your leaving is a terrible idea." Bush asked whether he should oust Gen. Richard Myers instead. Rumsfeld replied that he would be "firing the wrong person."

But as commentators demanded his head, Rumsfeld still contemplated leaving, even after Dick Cheney told him that he had to stay. In May 2004, when Bush visited the Pentagon and then repaired to Rumsfeld's office, the secretary handed him yet another I-quit letter. "I have concluded that the damage from the acts of abuse that happened on my watch, by individuals for whose conduct I am ultimately responsible, can best be responded to by my resignation," it said.

Bush rejected the idea. Rumsfeld said his mind was made up. But Bush would not accept the resignation, and Rumsfeld says he eventually accepted the decision.

To no one's surprise, he staunchly defends the treatment of terror suspects. One of his "biggest disappointments," Rumsfeld writes, was his inability "to help persuade America and the world of the truth about Gitmo: The most heavily scrutinized detention facility in the world was also one of the most professionally run in history." He flatly rejects "irresponsible charges" to the contrary by human rights groups, editorial pages and "most shamefully," members of Congress.

While Rumsfeld opposed waterboarding by military personnel, he saw "no contradiction" in arguing that it was an appropriate technique for the CIA to use against key suspects. He approved other interrogation methods for DOD, scrawling on one memo: "However, I stand for 8-10 hours a day. Why is standing limited to 4 hours?" That was a "mistake," he writes, but not a signal "that it would be okay to stretch the rules."

One sentence seems to sum up the Rummy attitude: "Never much of a handwringer, I don't spend a lot of time in recriminations, looking back or second-guessing decisions made in real time with imperfect information by myself or others." That is clear when he touches on what is widely regarded as a strategic blunder, the failure to put more boots on the ground early in the Iraq invasion. "More troops do not necessarily mean a greater chance for success," he writes.

Rumsfeld returns to the subject of Afghanistan late in the book, seeing "encouraging signs of progress" in 2006 "alongside harbingers that the real fight for Afghanistan's future was yet to come." But he never truly grapples with why the so-called good war is still raging a decade after the Taliban were driven from power and Hamid Karzai took nominal control of the country. His war narrative ends in Iraq with the beginnings of a counterinsurgency strategy that would yield substantial gains once Bush ordered a surge in American forces.

By then, Rumsfeld would be gone. He says he decided in the summer of 2006 that he would definitely quit if Democrats took control of either house of Congress that fall. Having passed the word through his old friend Cheney, Rumsfeld says he was surprised when Bush said on Nov. 1 that he wanted his Pentagon chief to stay "until the end."

But it was the vice president who called with the news, while Rumsfeld and his wife were having dinner shortly before the election: "Don, the president has decided to make a change."

Rumsfeld handed Bush the official letter in the Oval Office on Election Day. The president asked if Joyce was all right. "This is hard for me," Bush said. "You're a pro. You're a hell of a lot better than others in this town."

It is undoubtedly Rumsfeld's hope, as he begins the inevitable media blitz, that others will conclude the same after reading the book. But it contains few surprises and, after so many years of divisive debate, is unlikely to change many minds. What is known is that he has in these 50 chapters marshaled his best defense; only history's final verdict remains unknown.

Joel Schectman contributed to this report.

Howard Kurtz is The Daily Beast's Washington bureau chief. He also hosts CNN's weekly media program Reliable Sources on Sundays at 11 a.m. ET. The longtime media reporter and columnist for The Washington Post, Kurtz is the author of five books.