Public apologies are always difficult, and nothing makes that clearer than the fundamentally unapologetic apologies that Donald Trump and Olympic, gold-medal swimmer Ryan Lochte have issued recently.

Both men should take a lesson from President Ronald Reagan, who in 1988 showed what a true apology looks like when he signed a bill providing restitution for the World War II internment of Japanese-American citizens.

Even with his hawkish views, Reagan did not regard it as a sign of weakness to issue an unambiguous apology. In his signing speech, Reagan pointed out that during the war more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were taken from their homes and interned “without trial, without jury” because of fears “based solely on race.” No restitution could, Reagan went on to say, make up for these lost years. What was at the core of the bill he was signing was a matter of honor.

“For here we admit a wrong; here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law,” Reagan declared. Reagan made it impossible to doubt his words. His apology was unambiguous. It came without excuses. It was specific about those to whom it was directed. And it was accompanied by amends in the form of payments to the 60,000 surviving Japanese Americans who had been interned as a result of President Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order 9066.

The contrast with Trump and Lochte is striking. Reagan’s public apology put the nation and its values first. Trump’s and Lochte’s public apologies centered on themselves.

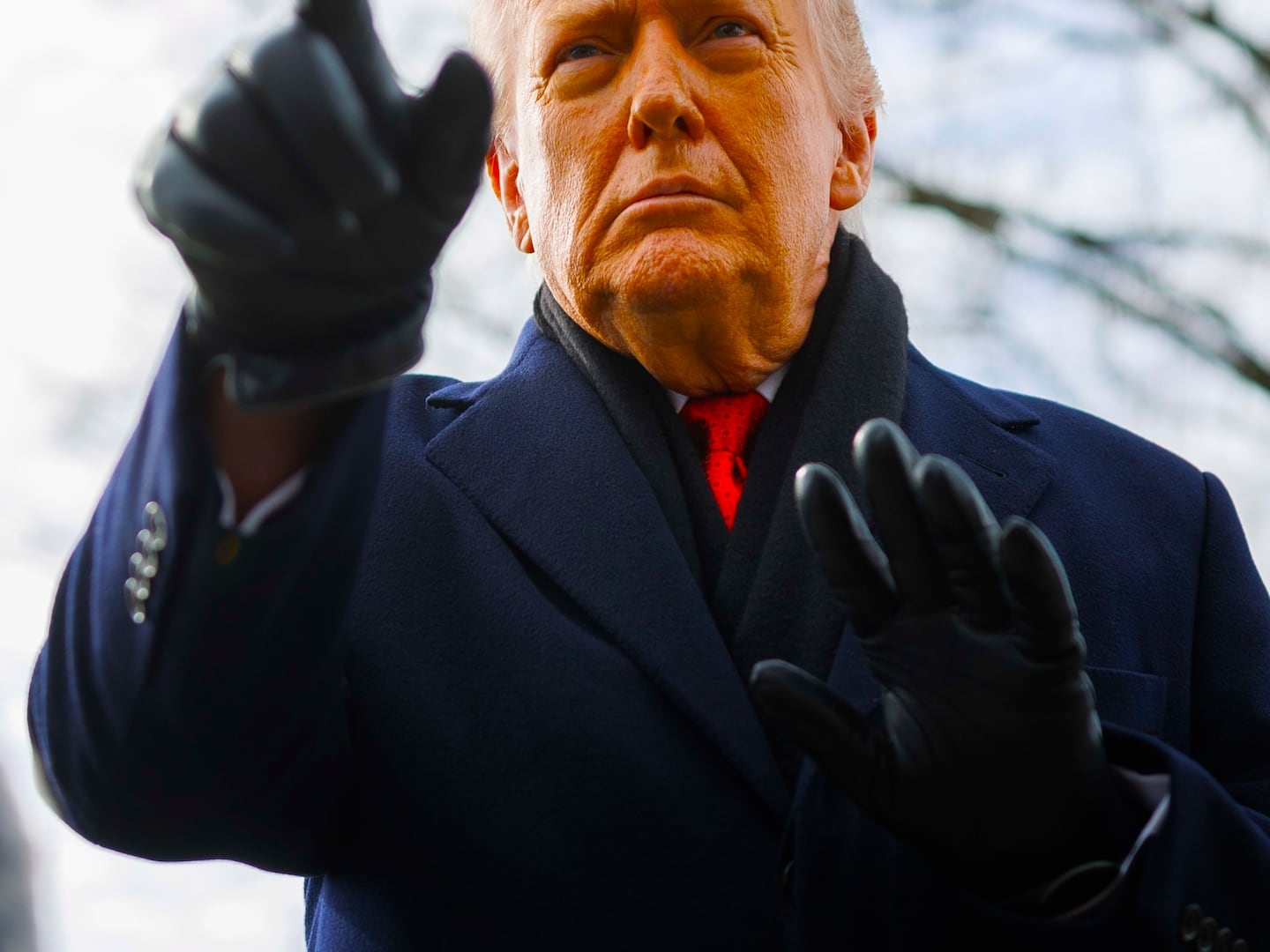

In his apology, made during a campaign speech in North Carolina, Trump acknowledged that he had failed at times to “choose the right words.” He regretted that, “particularly where it may have caused pain.” But no individual, neither Senator John McCain, whose Vietnam war record Trump disparaged, nor the Gold Star Khan family, whom Trump attacked for their criticism of his anti-Muslim views, is cited by name in his speech.

Trump then goes on to minimize his wrong doing by saying it occurred in the “heat of debate” and to imply that his harsh words were a product of his candor. “I can be too honest,” he declares, as he pivots from his four-line apology to a stump speech on why he should be president and why Hillary Clinton should apologize for her misdeeds.

Ryan Lochte’s apology, which he posted on Instagram, is equally self-serving in its description of what happened to him and his Olympic teammates in Brazil. Lochte never acknowledges that the incident he first called a robbery involved security guards preventing him and his swimming companions from leaving a gas station they had just vandalized before paying for the damages.

“I want to apologize for my behavior,” Lochte says. It turns out, though, that what he really wants to apologize for are not his actual deeds nor his lying but primarily his poor choice of words. It is “not being more careful and candid in how I described the events of that early morning” that Lochte says he is sorry about. Neither the owners of the gas station he trashed nor the people of Brazil, whom he implied were lawless, are central to his written apology. As far as Lochte is concerned, he should not even be judged too harshly. He was, after all, out late with friends “in a foreign country—with a language barrier.”

The unapologetic apologies of Trump and Lochte are rooted in a tradition that says apologies should be avoided whenever possible. It’s a tradition epitomized by John Wayne, playing a cavalry office in the 1949 western She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. “Never apologize, Mister. It’s a sign of weakness,” Wayne gruffly tells a younger officer.

In his speech on the internment of Japanese Americans, Reagan showed how, in the hands of a public figure with deep convictions, such thinking about apologies makes no sense. But Reagan, we should recall, is tapping into a tradition with much deeper roots than John Wayne. In American literature, we have the moving apology Mark Twain’s Huck Finn makes in the pre-Civil War South to the slave Jim after he has played a cruel trick on Jim.

And in international affairs, the apology has been a staple of strong leaders. West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, who fled Nazi Germany and fought in the resistance during World War II, made one of the most dramatic apologies for a country in modern history in 1970, when on a state visit to Poland he silently dropped to his knees before a monument to the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto.

In 1998 Pope John Paul II made an equally memorable apology in a letter he wrote approving a Vatican document that spoke openly of the failures of the “sons and daughters of the church” during the Holocaust. For Brandt and John Paul II, as for Reagan, there was no backlash. Unlike self-serving apologies, genuine ones restore communities and nations.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Every Army Man Is with You: The Cadets Who Won the 1964 Army-Navy Game, Fought in Vietnam, and Came Home Forever Changed.