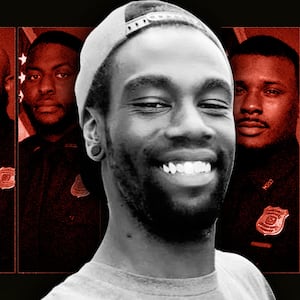

Last week, Sheldon Thomas walked out of prison, after having served 18 years of a 25-year sentence for a crime he likely didn’t commit.

Thomas’ path to incarceration began in 2004, when NYPD Detectives Robert Reedy and Michael Martin showed a picture of a young Black man to a witness, who identified him as being in the car linked to a shooting.

The photo was of someone named Sheldon Thomas, but it was not the Sheldon Thomas who would soon lose almost two decades of his life to unjust incarceration. Later, once those same detectives realized they busted the wrong Sheldon Thomas, they proceeded to build the case against him anyway.

Prosecutors also knew about the false identification, before and during Thomas’ 2006 trial. Eventually, so did Vincent Del Giucice—the judge who sentenced Thomas to a quarter-century behind bars, but later did not vacate Thomas’ sentence or order a new trial once he learned of officers’ lies—according to the Brooklyn district attorney’s office.

Michael Raskin, one defense attorney involved in the case, said, “In 14 years, I’ve been both a prosecutor and a defense attorney, and quite frankly, I’ve never seen anything like this.”

The New York Times reported that it’s unclear if anyone would face disciplinary measures for their actions in Thomas’ case. Notably, Detectives Reedy and Martin—both since retired with all the attendant benefits—throughout their policing careers had numerous complaints of misconduct filed against them to the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB). Reedy was accused of excessive force and illegal search. Martin was accused in four separate incidents of dragging, cursing, and slapping people. And “Intentionally making a false official statement regarding a material matter will result in dismissal from the Department, absent exceptional circumstances,” is part of the NYPD’s patrol guide.

The department often gets around that rule by downgrading “lying” to “misleading,” in disciplinary reports. But “misleading” is so pervasive that there’s a running joke within the NYPD about the practice of “testilying.”

Upon his release, Thomas said he forgave them. But we shouldn’t extend the same grace to the officers of our criminal justice system (including the judge and lawyers) whose lies and inaction put a teen in prison for almost two decades.

What we should do is make the public aware of this egregious case of injustice, so that voters might demand meaningful accountability for agents of the state who are empowered to take away people’s freedom.

It’s far past time to end the circular debates about whether we need more or fewer cops. What we need is to be more aggressively identifying and firing bad cops.

The same goes for prosecutors who knowingly distort the justice process by hiding evidence: demand that district attorneys fire their subordinates who engage in such practices. And if they won’t, vote the DAs out of office at the first opportunity.

Thomas’ case is not a random outlier. Scott Hechinger, a former defense attorney and criminal justice advocate told The Daily Beast, “The horror of what happened to Sheldon Thomas is just the most extreme kind of example of what happens every single day, en masse in the criminal legal system.” He added, “Police lies and embellishments in paperwork about stops, searches, and arrests, flawed identification procedures that lead to misidentifications, and prosecutors and judges turning a wilful blind eye to blatant misconduct or even outright innocence [are] a routine occurrence in our criminal courts.”

So what should be done?

New York City needs to expand its compensation fund for victims of police misconduct. You can’t give people their years back, but you can make their remaining ones less painful.

The DA’s office needs to review every single case these detectives touched, to set the precedent that the consequences for this kind of misconduct will not have a statute of limitations—nor will they be forgiven, the way Thomas has offered his.

And the CCRB must be empowered with actual power. It is virtually the lone watchdog that focuses on NYPD misconduct, and when a claim is substantiated and the charges are serious enough for the CCRB to recommend termination—in virtually all cases, the commissioner (who has the power to veto) either deems the officer “not guilty” or downgrades the consequences to docked vacation days. (Between 2021 and 2022, NYPD Commissioner Keechent Sewell rejected more than 70 CCRB disciplinary suggestions.)

Writing in the New England Law Review, civil rights and criminal defense lawyer Joel Berger notes that the NYPD stands apart in its secrecy and lack of accountability for officers.

“Never have I encountered a government agency more resistant to reform, more determined to hide its infirmities from the public, more prone to sweeping under the rug even the most hideous misconduct of its employees, and more successful in enlisting other agencies of city government to enable its penchant for secrecy,” Berger wrote. He advocates for eliminating the NYPD trial room—the forum where disciplinary charges are adjudicated by officials appointed by the police commissioner.

“This presents a significant problem: unlike most judicial or quasi-judicial officials, they are not independent and are therefore highly susceptible to the internal politics of the NYPD and can be pressured into making inappropriate decisions,” Berger adds. He also observed that the CCRB complaint process privileges the NYPD. “But when victims of misconduct file civil rights lawsuits, they unfortunately encounter another city agency that is every bit as determined as the NYPD to sweep police misconduct under the rug.”

“We should be outraged by what happened to Sheldon Thomas,” the former defense attorney Hechinger says. “We should be even more outraged that his case is just one example of how the system works.”