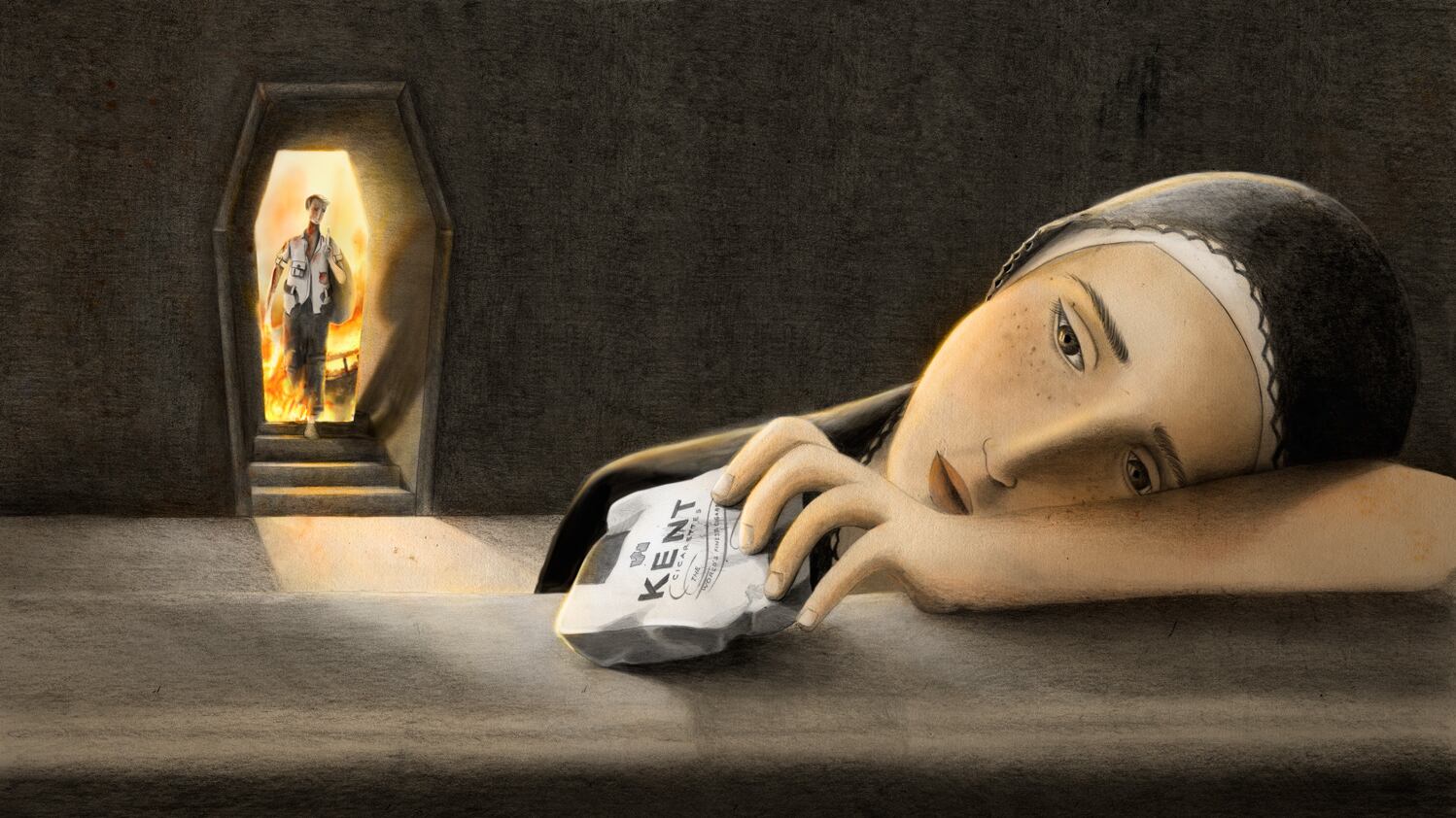

Fleeing their homes, many Syrians left behind middle-class lives; most arrived with none of the mementos that stir memory. Fedaa was different. She brought things. Diaries. Drawings. A pillowcase that she’d used since childhood. An empty pack of her brother Mustafa’s Kent cigarettes.

How best to explain what Syrians have faced over the last four years?

Numbers tell part of it: More than 191,000 people have been killed since the outbreak of the civil war in March 2011, a third of them civilians, according to the United Nations' human rights office. An estimated 9 million have fled their homes.

Photographs offer frozen moments that hint at a larger story, such as those showing the wrapped bodies of Syrians killed in the Damascus suburbs in August 2013 by the nerve gas sarin.

But researchers say recall and storytelling work on the brain in unique ways.

As one person recounts a memory to another, functional magnetic resonance imaging scans show the same parts of the brain light up in both the storyteller and the listener—parts, scientists say, that would be activated if both were experiencing the events in present time.

Over recent days in northern Lebanon, I worked with Concern Worldwide's Taline Khansa and a Lebanese illustrator, Hanane Kai, to capture the lives of Syrian female refugees being supported through Concern's work.

We hoped to move beyond "el azmeh,"—"the crisis," as they refer to the fighting that sent them from their homelands—to a more complete understanding of their memories.

Fedaa was born into a comfortable home in Homs, Syria, but her first recollections were of trouble. Before her birth, her then-five-year-old brother was killed by a mentally unstable uncle, and she remembers seeing her mother, years later, hysterically pull his bloodstained clothes from drawers.

Her mother, pregnant at the time of the killing, was hit in the shoulder by a bullet from the same gun that killed her son. The baby was stillborn. Fedaa was born next, and two years later, Mustafa. There were nine children in all then, and she and Mustafa were especially close. They played together, made spears from sticks and sharp rocks, chased chickens together. Later, he taught her how to smoke, and still later, they whispered of politics, and fears and hopes for their futures.

Fedaa was an artist from the start, winning first place in a competition when she was six years old. She stayed in school until 9th grade, when her father pulled her out. She was engaged a year later to a man 11 years her senior, chosen by her father. She felt conflicted, but did as she was told.

It was a simple wedding because the groom was not well off. He was very conservative; he insisted she keep her face covered all the time. She got pregnant quickly, spent two days in labor and then gave birth to Nabigha. “My daughter was my doll,” she said. Fedaa’s second daughter was born two years later.

By then, though she couldn’t imagine living with the shame of divorce, she’d begun to pray that God would create a way for her and her husband to separate. Eventually, she began leaving her husband for short periods to return to her parent’s home. Finally came the day she told her parents she was too unhappy to return. In response, her husband prevented her from seeing her daughters for extended periods.

Then began “el azmeh.” Her brothers formed a group to rescue people after a rocket attack. “Mustafa and I were still very close—I think I was closer to him than his own wife,” Fedaa said. “Sometimes he would return home with blood on his shirt from trying to save friends. At first I avoided the demonstrations. But I changed. I started to become political.”

Then came the day Mustafa, along with two others, was killed by a mortar shell. Speaking of it now, Fedaa’s words slowed and her eyes went unseeing. Mustafa, she said, was buried near a checkpoint in a gravesite she’s never seen.

To this day, she imagines him appearing at her door. “I see him often in my dreams,” she said. “He’s always wearing the clothes he wore when I saw him last. At first after he was killed, I told myself he’d made a sacrifice for freedom. I no longer think like that.”

After Mustafa’s death, time seemed to speed up. Only two months later, her youngest brother, Mohammed Muktar, disappeared. Two months after that, her oldest brother Omar was killed. Six weeks later, 16 young men from their area—nine Muslims and seven Christians—were killed for no reason that anyone could decipher, and Fedaa’s father decided to take what remained of the family to Lebanon.

Fedaa packed up some of her diaries and paintings, the key to her bedroom, the pillowcase she’d slept on as a child, and a now-empty pack of Kent cigarettes that had belonged to Mustafa. After all, he had taught her to smoke.

She and her family arrived in Lebanon on Oct. 17, 2012, at 1:34 p.m.—she marked it in her diary. Quickly, Syria became “a faraway dream.” Today, she and her family are among the 13,500 Syrian refugee families living in Concern-supported housing in northern Lebanon. Some 1.1 million Syrian refugees are currently living in Lebanon, making up one-quarter of the resident population.

Concern works in Lebanon with Syrian women and their families to provide shelter, safe water, education for children and protection services for all, but also to support their voices. "Concern will continue to amplify the voices of these women," says Concern Country Director Elke Leidel, "to make their stories heard, and to prevent the Syrian crisis from being forgotten."

Masha Hamilton is Vice President of Communications at Concern Worldwide, a global humanitarian organization committed to eliminating extreme poverty and improving the lives of the world’s poorest. She is a novelist and former journalist who has reported from Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Russia. She founded two non-profits, the Camel Book Drive and the Afghan Women's Writing Project, and worked in 2012 and 2013 as Director of Communications at the US Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan. She can be found on Twitter at @MashaHamilton.