If prisons are designed, first and foremost, to punish wrongdoers while protecting the rest of society from them, they also often make some effort to rehabilitate their residents. Such is the case at California’s Folsom State Prison—a locale most famous for hosting the 1968 Johnny Cash concerts that resulted in his legendary live album (At Folsom Prison)—which seeks to repair inmates through an unconventional program that involves interaction with members of the outside world. At once intense and affecting, theirs is an eye-opening means of transformation-through-confrontation: Part spiritual journey, part psychoanalytic inquiry, and part wild-eyed exorcism.

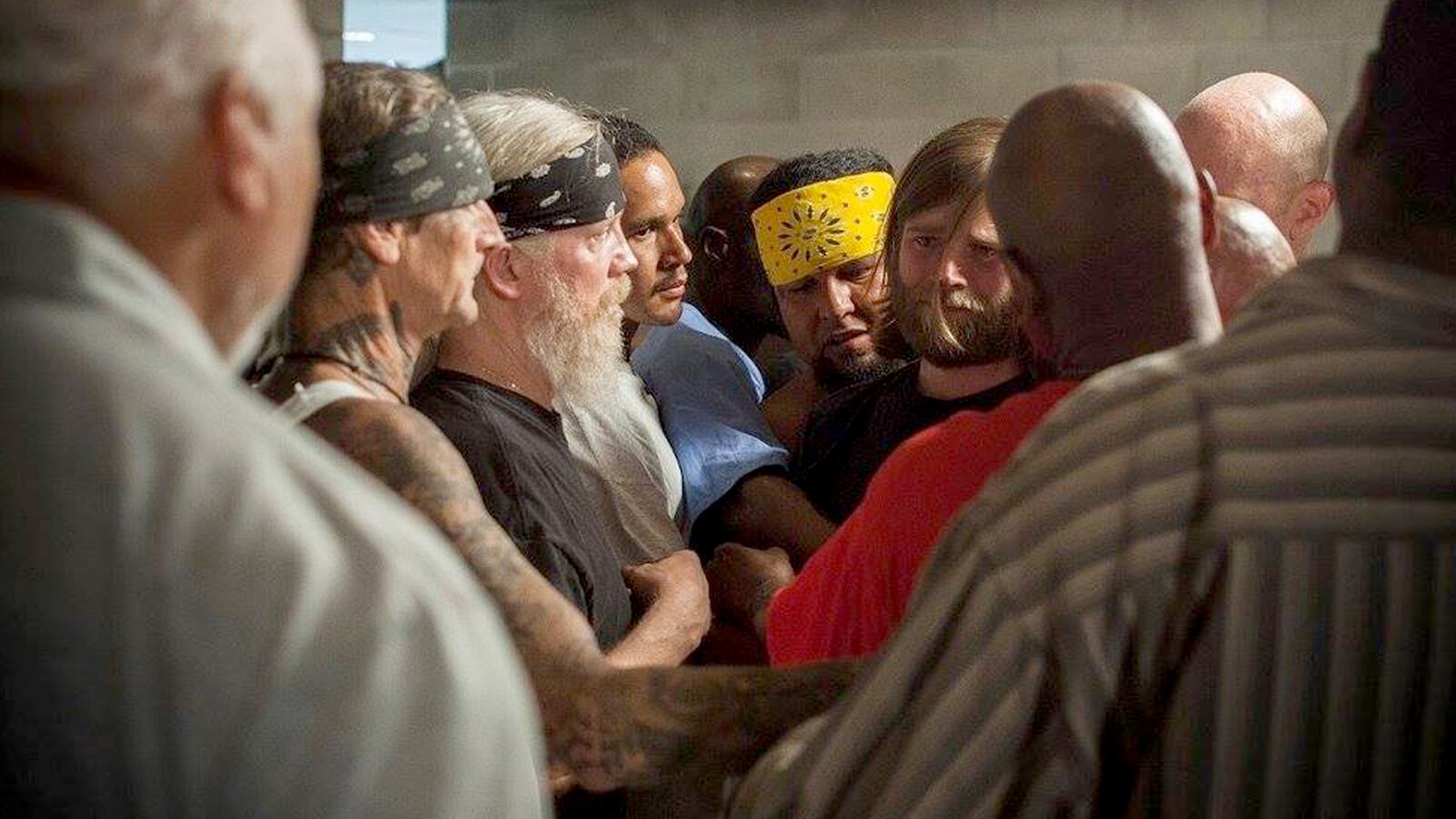

Jairus McLeary’s doc The Work (co-directed with Gethin Aldous) is a riveting account of Folsom’s unusual methods of treating inmates, focusing on three everyday citizens as they venture to the institution for a rigorous program alongside some of the state’s most vicious murderers and gang members. For four days, bartender Charles, museum associate Chris and teacher’s assistant Brian (as well as many others) sit, side-by-side, with convicts in a circle in a large indoor prison square, where they discuss the traumatic behavior that got them to where they are—or, in some cases, the reasons they fear winding up in a place (i.e. Folsom) they want to avoid. It’s hardcore group therapy, with the guilty and the innocent striving to find common ground in order to transcend their kindred inner demons.

There’s no actual possession in The Work, but it’s hard not to draw parallels between reality and supernatural fiction when Brian—an arrogant and judgmental young man who spends the better part of his Folsom time pissing off fellow program members—lets out a deep, unholy guttural scream while trying to publically wrestle with his problems. Attended by free and incarcerated men of their own accord (with the latter agreeing to leave gang politics and racial animosity at the door), it’s a course of resistance, defiance and painful expression. Through heartfelt admissions and rugged expulsions of anger and sorrow, it tries to function as a radical, in-your-face cure for the toxic masculinity that compels so many men to commit heinous acts (murder, rape, assault, armed robbery, etc.) and, in turn, to throw away their futures for lives behind bars.

The initial question hanging over The Work is simple: why would individuals like Charles, Chris and Brian agree to such a harrowing ordeal, when their personal issues—whatever they might be—haven’t yet triggered criminal conduct? At the outset, McLeary’s film is cagey on that point, instead merely taking their word that they’re eager to confront their rocky upbringing (Charles), figure out why they feel so “stuck” (Chris), and investigate their attraction to a sense of “danger” (Brian). Upon entering the facility, they’re tasked with pairing up with two inmate partners of their own choosing. For Brian, that leads to Vegas, a thin African-American alum of the Bloods who’s been locked up for nineteen years on a kidnapping-for-purposes-of-robbery charge, and who has a habit of getting in others’ faces and forcefully challenging them to break through their barriers (of shame, guilt, hopelessness) in a quest for catharsis.

Vegas’ methods are part and parcel of Folsom’s curriculum, which has men taking turns talking about their upbringings and mistakes until they’ve tapped into their underlying hurt—at which point the rest of the “circle” physically holds them down so they can scream, kick, and claw about as a means of fully expelling their fury and misery. For men whose lives have been rooted in uncontrollable violence, this process is a mind-and-body purge of their most corrosive feelings. And it allows them to be the very things that, inside Folsom, they cannot be: teary, emotional, vulnerable.

From Asian gang member Kiki, who desperately wants to drop his “armor” and mourn his sister, to former Aryan Brotherhood member Rick, who screams about how he’s “tired of motherfuckers getting hurt,” to Bharataji, a program facilitator who turned to a life of heroin after being emasculated by a trusted friend, digging deeply into trauma and experiencing something raw, and poignant—unshackled from their outward anger and violence—is liberating. And through their individual horror stories, the inmates, and Charles, Chris and Brian, discover that they’re linked by a very specific hang-up: uncaring, abusive and/or absentee fathers. It’s a root-cause explanation that sounds, on the face of it, like a cliché. Yet coming from the mouths of hardened criminals like Native American gang member Dark Cloud (in for attempted murder), who laments his decision to ditch his mother to be with his father—only to be raised on lessons that got him locked up for decades—it resounds with sledgehammer impact.

The Work doesn’t condone, or try to mitigate, its convicts’ ugly crimes. However, in a vein similar to Netflix’s recent comprehending-serial-killer-psychology series Mindhunter, it does empathetically treat them as human beings whose unique, awful personal travails—from birth to the present day—help explain their motivations. As such, it’s somewhat disappointing that both with his incarcerated subjects and with Charles, Chris and Brian, director McLeary doesn’t provide any substantial backstory material; what we learn about them comes almost exclusively from their “circle” sessions. We only get fragmented hints about their larger tales—a bits-and-pieces approach that’s certainly in keeping with his general fly-on-the-wall non-fiction strategy, but which sometimes leaves things disjointed and under-developed.

Still, even when a given scene, or incident, calls for greater clarification, and despite the fact that McLeary’s visuals are generally more functional than evocative, The Work is a bracing glimpse at the interior rot plaguing men on both sides of Folsom’s walls—corruption born, at least in part, from their status as fatherless sons. Whether true rehabilitation can ever be accomplished isn’t something McLeary’s film can definitively answer. There’s no doubt, though, that for those scarred by years of abandonment and mistreatment, and raised to believe that the only emotions worth feeling are hate and wrath, the path to healing is a scary, excruciating one. Or as one man says, “This is work. This is ugly ass shit.”