“My vision of the world at its brightest is such that life without the use of its amenities is impossible,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in 1930 in a letter to Oscar Forel, the Swiss psychiatrist who was treating Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda, who had suffered a breakdown. “I have lived hard and ruined the essential innocence [sic] in myself that could make it that possible [sic], and the fact that I have abused liquor is something to be paid for with suffering and death perhaps but not renunciation.” By some accounts Fitzgerald did renounce, not even touching a drop—at least so long as his lover, the gossip columnist Sheila Graham, was with him—during the last year of his life, although it was too late by that time. There is a spate of such letters and other evidence. Fitzgerald, to put it simply, felt that it was man’s duty to enjoy drink, as well as his right as a writer to dramatize and self-dramatize the power of drink.

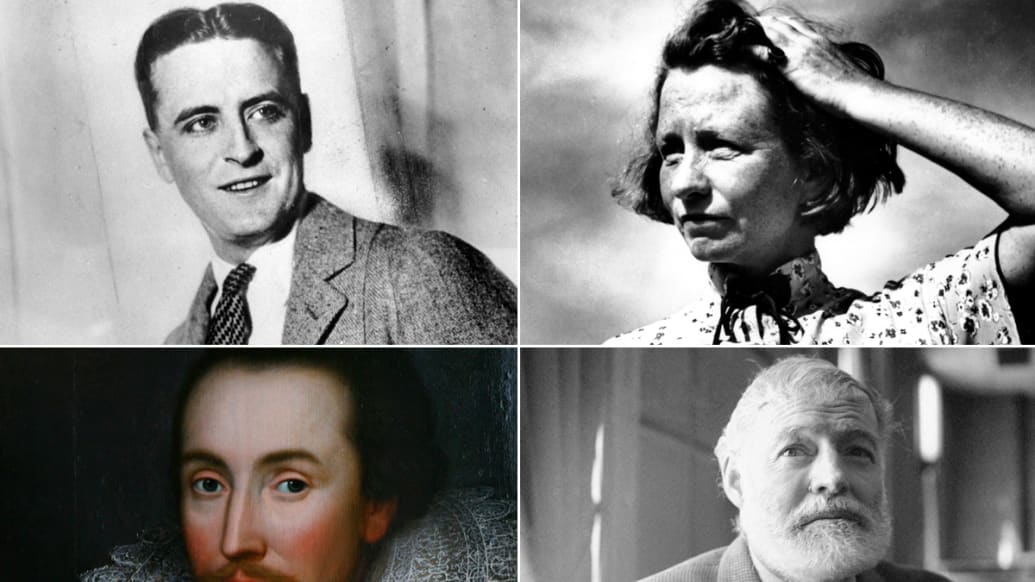

F. Scott Fitzgerald was born in 1896, famous by 1920, forgotten by 1936, and dead by the end of 1940. In the '20s, he introduced himself to party guests as “one of the most notorious drinkers of the younger generation,” or as “F. Scott Fitzgerald, the well-known alcoholic.” His friend Ernest Hemingway experienced such stagecraft firsthand when, during a trip with “Poor Scott,” Fitzgerald was convincing himself that he was dying of “consumption of the lungs” and demanded that Hemingway find a thermometer to ascertain whether a fever boiled in his blood. “He did have a point, though, and I knew it very well,” Hemingway wrote in A Moveable Feast. “Most drunkards in those days died of pneumonia, a disease which has now been almost eliminated. But it was hard to accept him as a drunkard, since he was affected by such small quantities of alcohol.”

As Thomas Gilmore asserts in Equivocal Spirits: Alcoholism and Drinking in Twentieth-Century Literature and John Crowley corroborates in The White Logic: Alcoholism and Gender in American Modernist Fiction, the fable of Fitzgerald’s Edgar Allan Poe–like low tolerance was likely just that—a fable, helped by an alcoholic’s tendency to sometimes conceal consumption and sometimes boast about overconsumption. But whatever the legend of his drinking capacity (Hemingway himself witnessed another time when Fitzgerald drank far more than he ever saw and was completely fine, even telling articulately the story of his and Zelda’s life), by the '30s Fitzgerald was not so much as capitalizing but clutching onto the persona of a washed-up alcoholic. He was obsessed with his great literary promise and the even greater subsequent disappointment, knowing that alcoholism was behind it but had not been the sole cause of a tragedy so immense (to him). At his lowest point, in 1935, he claimed to have “not tasted so much as a glass of beer for six months,” which was likely untrue.

This practice of constant mythmaking and denial offered Fitzgerald perhaps the most painful decline of all the great novelists. He wasn’t so much a victim of alcoholism as the very embodiment of alcoholism—or the stages of alcoholic recovery, in reverse. He was so submerged in drink that he didn’t even need to write about booze for us to connect his thoughts to booze. His words and his life had all the makings of a stiff drink, in all its nighttime glamour and morning gravity.

As if it had been ready and waiting, New Directions has published a slim volume of Fitzgerald, provocatively entitled On Booze but demonstrably lacking in his booziest writings. Missing are the short stories: The early delirium of “May Day,” with a group of privileged Yale alumni soaked in champagne as riots roared in the background; and the past-tense plaintiveness of the later “Babylon Revisited,” a brutal morning after following a decade of boozing if there ever was one.

Still, On Booze is a wonderful title. The temptation is to read it as “about” booze. It is not. The best writings on drink are never really about drink. The real subject of Fitzgerald’s particular brand of alcoholism is the long sink from the ebullient down to the dregs of the bottle, and at last when it empties and crashes to the ground. And for that experience, included in On Booze, we have the sketches, notes, and letters, published after Fitzgerald’s death under the title The Crack-Up, compiled by the stately critic Edmund Wilson as an ode to his late friend. At the core of the collection are essays that Fitzgerald wrote for Esquire magazine in 1936—“The Crack-Up,” “Pasting It Together” and “Handle With Care,” three majestically grim, crumbling monuments that sees Fitzgerald, a writer who’d always been a singular chronicler (of, say, the Jazz Age) turning inward and backward—as always, Fitzgerald doesn’t simply record, but assesses and measures the cost. The man who was being paid $4,000 per piece by The Saturday Evening Post in 1930 was fetching only $150 a story from Esquire. His total book royalties in 1936 amounted to about $80. Soon he would go to Hollywood as a failure of a screenwriter, completing his fall. “One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise,” he wrote. Here was a withering mind filing a report on his vanished past. “Before him was not the dish that he had ordered for his forties. In fact—since he and the dish were one, he described himself as a cracked plate, the kind that one wonders whether it is worth preserving.”

Lest you think Fitzgerald’s emotional breakdown is rich material for melodrama thick enough to fill volumes, try doing it yourself—sometimes it just hurts too much to write about your own hurt. The Crack-Up isn’t long, and On Booze is a further abridgement of the already manageable 352 pages into 96. What we get is not an endless treatise on alcohol or alcoholism, but whiffs of a writer soaked in the stuff, a strong sensory experience on the type of life that Fitzgerald led.

As it is with wine, age matters. What life meant for Fitzgerald, in 1936, was very different from what it was like in 1921. Booze can break you down, but it can also bubble you to the surface, as it seemed to have done for the young Fitzgeralds. “Show Mr. and Mrs. F Number—”, authored by Scott and Zelda, offers snippets of their lives over the earlier years as they traveled from one grand hotel to another. “Disciplined by the long majestuous twilight on the river and we were young but we were impressed anyway by the Hindus and the Royal Processions,” they wrote, a sentence that tastes like a long flow of drink even if none is mentioned. And so it is that the collection isn’t “about” booze—Fitzgerald is just on booze. You can perhaps say he’s drunk, on love or on the rhythm and feel of the ‘20s air, on the promise of a high.