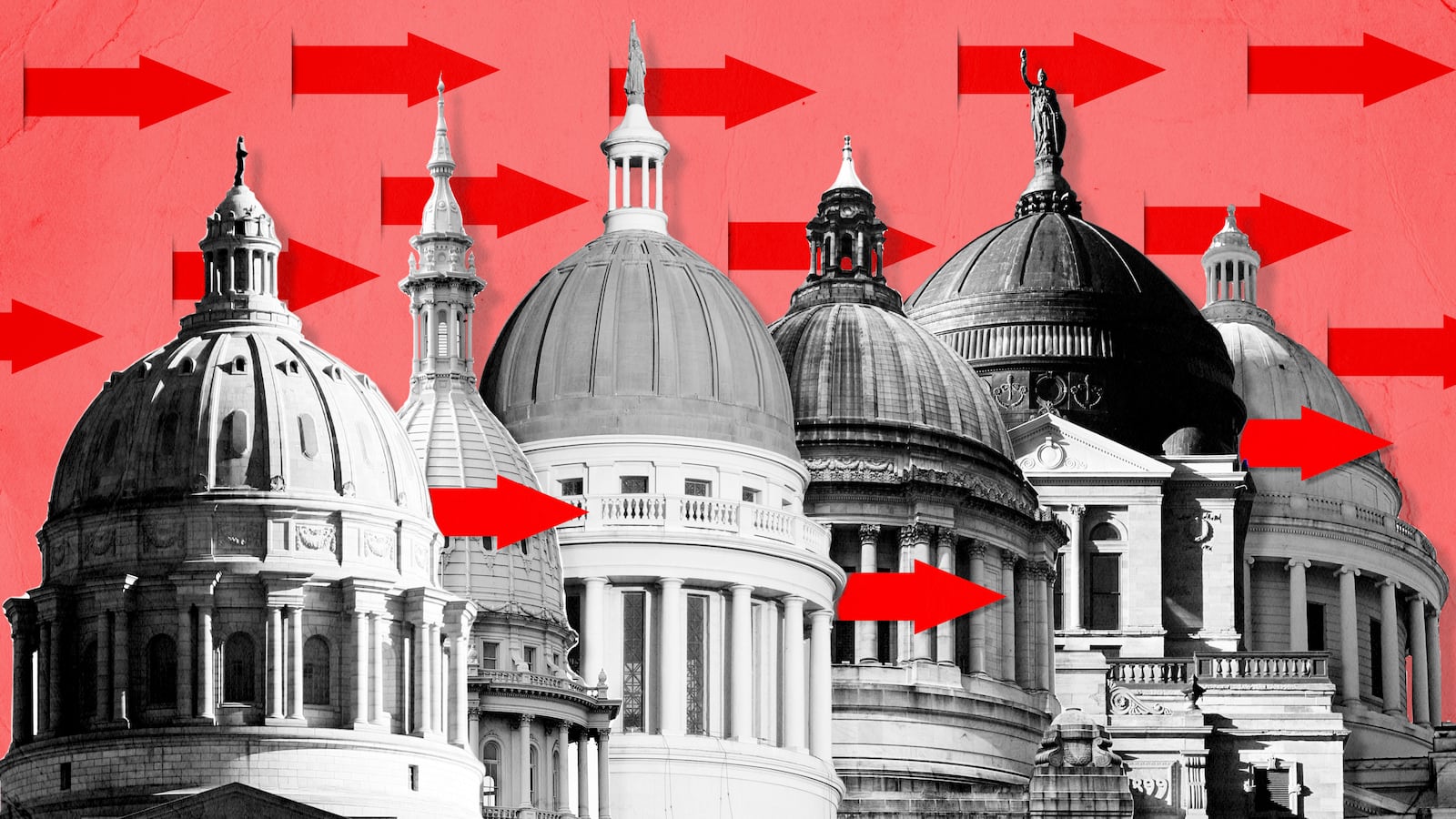

While Democratic candidates exceeded expectations in last week’s primary elections, state legislators with far-right ties amassed a quiet series of victories.

In May, the social justice nonprofit Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights (IREHR) released a troubling study of the country’s statehouses. IREHR’s survey identified 875 state legislators as members of far-right Facebook groups—21.74 percent of the country’s Republican state lawmakers. The midterm election did little to oust them from office. As of Monday afternoon, 97 percent of the fringe candidates who were up for election won their races.

Devin Burghart, IREHR’s executive director, said the win rate (currently 497 victories and 15 losses) represents “a pretty remarkable winning percentage. I think that’s larger than incumbency, generally.” (In 2020, 93 percent of incumbents won re-election, according to Ballotpedia.)

Those statehouse victories cut against the national-level narrative of the 2022 midterms as a Democratic win.

Far-right candidates aren’t necessarily running on broadly popular messages. Many oppose abortion rights, which most Americans support, or have connections to controversial groups, like extreme militia organizations. But oftentimes, the records of extremist candidates went under-examined.

“At a state level, where the far-right candidates were challenged on their far-right participation, they tended to lose,” Burghart told The Daily Beast.

But many of those candidates never saw a debate stage. Of the 875 lawmakers included in the IREHR’s report in May, “575 were up for re-election. Of those, 190 had no challenger whatsoever. 230 of them didn’t have a Democratic challenger,” Burghart said.

The IREHR conducted its initial survey by compiling a list of nearly 800 far-right Facebook groups dedicated to causes ranging from militias, to bigoted conspiracy theories, to abortion bans. While the 875 lawmakers who’d joined the groups by no means represent the full extent of the nation’s fringe-friendly politicians (many candidates are savvy enough to clear their Facebook history before running), they reveal a sample of legislators’ digital diet.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade this year placed a new urgency on state legislative races, removing federal abortion protections and allowing states to pass laws banning or enshrining certain reproductive rights. Civil rights watchdogs also warned that the Supreme Court ruling clears the way for similar decisions that would roll back federal protections for LGBTQ people and people of color, relegating their rights to state lawmakers. Even without the rulings, some state legislatures have taken recent aim at those communities, passing bans on gender-affirming care and gag rules against discussing topics related to race and gender in schools.

Many of those efforts remain underway in statehouses, even if a renewed Democratic majority in the Senate would currently block such laws at a national level.

“I think it’s a reminder that while there’s been a lot of effort at the national level to deal with some of the more high-profile candidates, that over the past few years, the problem of the far right has burrowed into state legislatures,” Burghart said. “It’s a problem where people haven’t yet stepped up and engaged to the degree I think is necessary to grapple with this problem.”