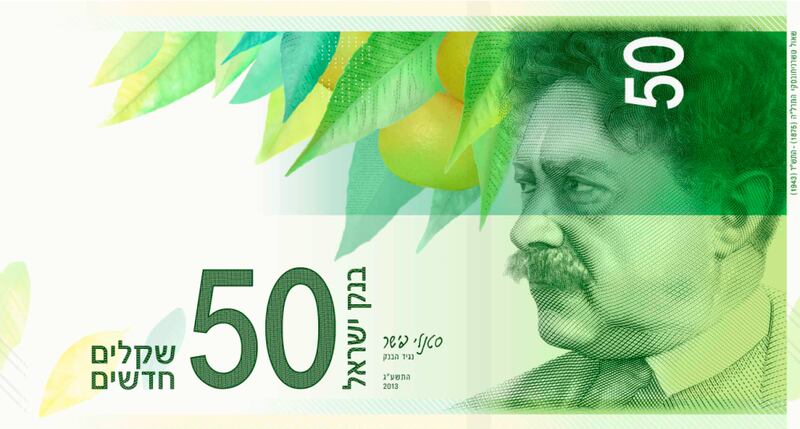

I bought a pair of tickets to Dudu Tassa and the Andalusia Orchestra performing the works of Tassa's grandfather and great-uncle, the Al-Kuwaiti Brothers, the forgotten Jewish maestros of Baghdad. The tickets set me back two Yitzhak Ben-Tzvis, the equivalent of one Zalman Shazar, which is to say two 100-shekel bills or one 200-shekel bill. By next year, when Israel's new banknotes are in circulation, that will be two Leah Goldbergs or one Nathan Alterman. Poets are replacing politicians on our money.

The concert cost considerably less than classical European music does at the same Jerusalem hall. Marginalized culture comes at a discount, and its icons don't appear on cash. The chances that portraits of Daud and Saleh al-Kuwaiti will ever adorn a 200-shekel bill seem slim. But you never know. After much controversy, Jerusalem has named a street after dissident philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz. The gates of commemoration are forever open.

The Leibowitz fuss had barely ended when the shouting about the banknotes began. Last week, at the Bank of Israel's request, the cabinet voted to approve the new bills. The poets Rachel Bluwstein—usually known only by her first name—and Shaul Tchernichovsky will appear on the 20- and 50-shekel notes, completing a quartet with Goldberg and Alterman. Arye Deri of the Sephardi ultra-Orthodox Shas party, now in opposition, demanded to know why only Ashkenazi poets were honored. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu responded that the next set of banknotes—likely to be issued in another 15 or so years—would include one with an image of Rabbi Yehudah Halevi.

By implying that the last Sephardi poet to warrant commemoration lived 900 years ago, Bibi did not placate critics. Haaretz blogger Benny Ziffer gave a list of much more recent candidates. "Have you heard of Shoshana Shababo, you ignoramuses?" Ziffer asked. If he was getting hot around the collar, Ziffer said caustically, it was "partly because I'm one of those hot-headed Levantines."

As a recovering ignoramus, I ordered a used copy of Shababo's Love in Safed before I finished Ziffer's post. The novel describes the clash of romantic love with family and tradition in a small Jewish community emerging into modernity. Were the community in Galicia, were the women cursing in Yiddish in the marketplace, the novel might have entered the Israeli literary canon. Instead, the story is placed in the Levantine backwater of Safed, the Jewish women curse in Arabic in the market, and the handsome, modern Jew is from Damascus. After two mostly ignored novels, Shababo spent the rest of her life working in what Isaac Babel called the "genre of silence."

Yes, I know. Safed is in the Jewish homeland, which one might think is in the Levant. Geography is slippery, though. The poet Haim Gouri once told me how, in 1955, he brought Nathan Alterman to the barbed-wire borderline cutting through Jerusalem. "From here to Shanghai is Asia," Alterman said, "and from here to the beach in Tel Aviv is Israel." Israel wasn't in Asia. It lay on an imaginary map of Europe, somewhere between Minsk and Vienna. The proper melodies for putting Hebrew poems to music were Russian, and mostly mournful.

Back to the money: I had to look in my wallet to remember who's on today's Israeli currency. I grew up with American cash, but I only recall that Lincoln is on the five-dollar bill because Raymond Chandler mentions it in a short story as a detail that a sharp-eyed detective forgot. A month after the new notes enter circulation, seven out of 10 Israelis won't remember whose faces are on them.

Nonetheless, the new monetary pantheon is a symbol, and an accurate one, of official culture and education. Israeli-born artist Meir Gal's photographic work, "Nine Out of Four Hundred," shows how many pages of his 1970s high school textbook in modern Jewish history were devoted to Jews in Muslim countries. The curriculum has become only marginally less Eurocentric since then. Written Arabic is supposedly a required subject in Jewish junior highs, but schools ignore the requirement with impunity. The problem is not only the message to Mizrahim and to Palestinian Israelis that they don't belong. It's the intellectual and cultural impoverishment of the country, the obdurate unwillingness to acknowledge that we are in the Middle East and to be enriched by it. Those of us whose grandparents did come from somewhere between Minsk and Vienna also lose out.

That concert, by the way, wasn't merely superb, it was charged. It was haunted. Toward the end of one piece by the Al-Kuwaitis, Dudu Tassa stopped singing. The recorded voice, almost precisely like his, of one of the Baghdad brothers, completed the song. The audience trembled and clapped. For my money, the evening was worth a stack of Altermans.