Frank Schaeffer saw the birth of the religious right from the inside. His father, the brilliant Presbyterian theologian Francis Schaeffer, was the intellectual father of the movement. He channeled the countercultural spiritual yearnings of '60s-era Jesus Freaks into the right-wing movement that now dominates the Republican Party. It was Schaeffer who first led evangelicals to mobilize against abortion, for many years ignored as primarily a Catholic concern. His three-party documentary, How Should We Then Live?. which Frank produced, inspired a whole generation of evangelicals into politics, including Michele Bachmann, who cites it as a formative influence. As his son, Frank was a conservative Christian celebrity in his own right, keynoting the Religious Broadcasters Convention and the Southern Baptist Convention.

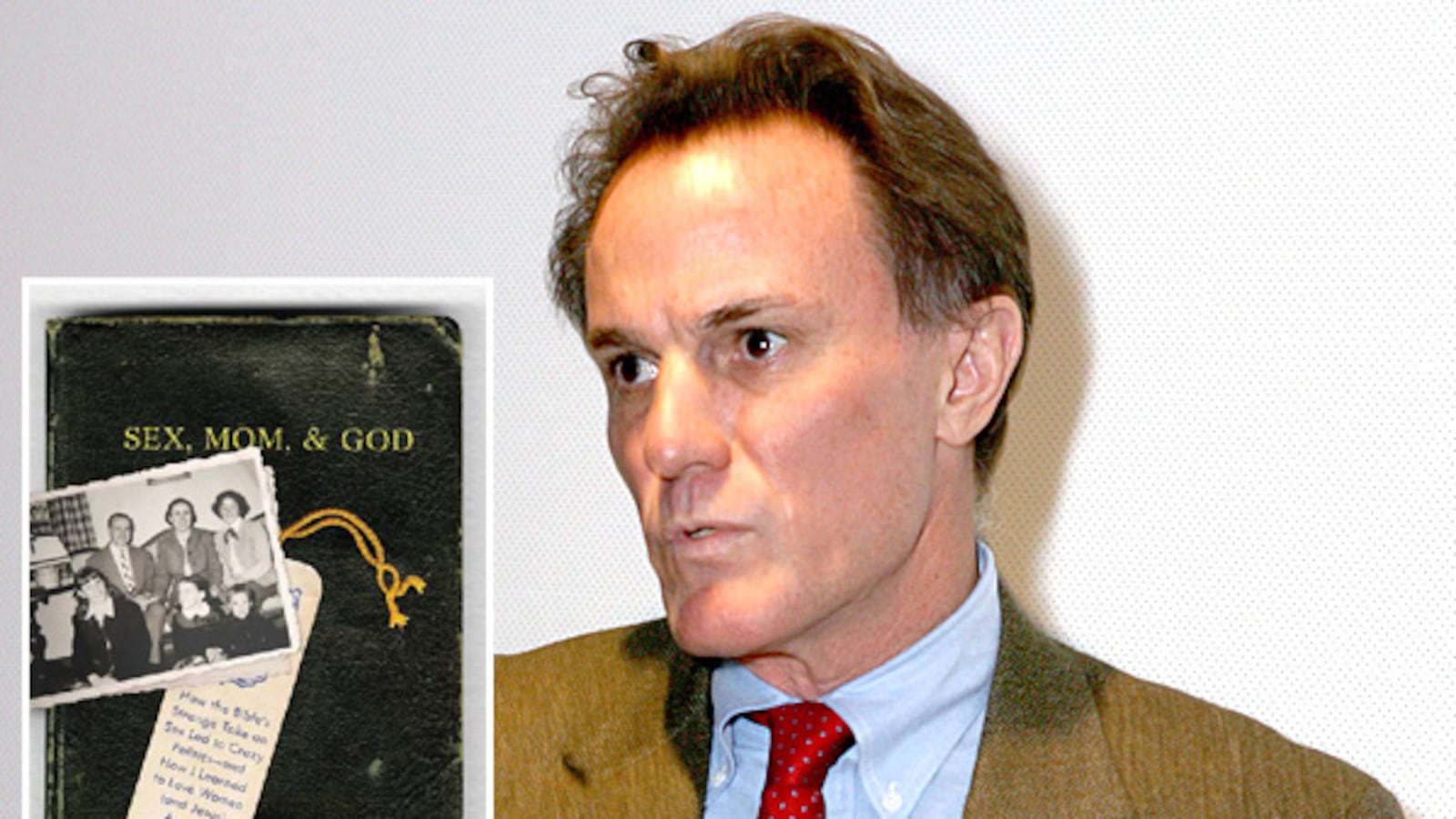

Now, though, he has a new message. The Christian right, he says, is fundamentally motivated by an anxious, terrified obsession with sex, an obsession that once drove him as well. “Since the 1970s, the American culture wars have revolved around a fear of sex and women no less insane and destructive than any horror story to come out of Afghanistan,” he writes in his intriguing if hyperbolic new book, Sex, Mom and God.Of course, to many critics of the religious right, Schaeffer’s argument is a truism. To sympathizers of the movement, it will probably seem, at best, condescending and simplistic. But his privileged view of the Christian right’s sexual weirdness makes his account particularly interesting, and helps explain why the aggressively pious so frequently destroy themselves with sex scandals.

Sex, Mom and God is actually Schaeffer’s second memoir about his odd hothouse coming of age. His first, 2007’s Crazy for God: How I Grew Up as One of the Elect, Helped Found the Religious Right, and Lived to Take All (or Almost All) of It Back, was built around his larger than life father. This one is centered on his adored, paradoxical mother, Edith Schaeffer, an author who wrote books for Christian women like The Hidden Art of Homemaking. Edith was a fascinating character, at once a strict fundamentalist and a sophisticated, warm-hearted aesthete. “Mom was a much nicer person than her God,” Schaeffer writes.

Their household was far from what one would imagine as a seat of evangelical royalty. His parents had gone to Switzerland in the late 1940s as missionaries, and in 1955, Francis Schaeffer founded L’Abri—French for “The Shelter”—a Christian community that was part fundamentalist compound, part intense intellectual salon, and part hippie commune. Growing up there, Frank Schaeffer wrote in Crazy for God, “it was not unusual to find myself seated across the dining room table from Billy Graham’s daughter or President Ford’s son, or even Timothy Leary.”

While the Schaeffers promulgated an austere Calvinist theology, they were also art-loving sensualists who holidayed by the sea in Portofino, Italy. (Edith would instruct young women, “[A]lways remember that there’s no reason that Real Christians can’t look like Vogue models!”) In his son’s telling, Francis Schaeffer was a man given to terrible rages who regularly hit his wife. He was also sexually voracious. The book’s creepiest passages feature Edith regaling her young son with the details of her sex life. “Your father demands sexual intercourse every single night and has since the day we married because he doesn’t want to end up like King David!” she announces, telling him about the patriarch’s sinful dalliance with Bathsheba. When Frank was 8, she showed him her diaphragm.

Schaeffer loves his mother a great deal, and reading his book, it’s not entirely clear that he grasps how wildly inappropriate her confidences were. Rather, he sees her fulsome interest in sex as a small rebellion against the fundamentalist world that she was born into. “Who was Mom as she might have been if part of her brain had not been crippled by her missionary parents’ indoctrination of her, just as the bones of the feet of little girls in China were once deformed by food-finding?” he wonders.

Of course, there are always gaps between people’s private lives and public selves. But Schaeffer insists that among those who imagine themselves God’s elect, they’re more like chasms. “I don’t really know anybody on a big leadership scale in the evangelical world who I would say have survived a little scrutiny,” Schaeffer says by phone from his home in Massachusetts. “The mix of power, money and fame is noxious. When you add in that you are the voice of God on top of it, it’s the most toxic mix you can imagine.”

Part of what’s at work, he says, is a powerful elitism. For his father, using pornography was just a small personal vice, even if he saw the society-wide spread of porn as a harbinger of moral collapse. “What he would wink at individually or indulge in himself, becomes anathema when it’s part of a wider social problem,” says Schaeffer.

Having grown up around this sort of hypocrisy helps him to understand the endless parade of social conservatives who’ve been caught up in sex scandals. “What people don’t understand is they really mean it when they say society would fall apart if everybody did this. When it came to themselves, it’s OK—this is just my little personal sin here.”

But the alternative to hypocrisy—fidelity to impossible standards—has its own dangers. The rage of many fundamentalists, he suggests, comes from a Sisyphean struggle against the body’s demands. “You must ‘stand against all compromise’; you must hate every ‘deviation’ because you are in a constant battle with temptation,” he writes. “Maybe your temptations lead you to question what you say you believe…So you don’t open a door to doubt; rather, you just yell all the louder to drown out the nagging thought that you may, after all, be no better than anyone else and may be just as ‘Lost’ as the next guy.