Lush foliage and vivid yellow flowers surround a bright blue wall proclaiming “Frida y Diego vivieron en etsa casa, 1929-1954.”

Visitors pass this entrance and enter an oasis of nature—zinnias, calla-lillies, Lady’s Eardrops, giant green philodendron leaves—an explosion of color and plants and flowers cocoon the garden paths.

More varieties of cacti than have possibly ever shared the same space rise in all their prickly glory out of flower beds and terra-cotta pots.

One could be forgiven for thinking some weird twist of fate has magically transported you to Mexico City. But this isn’t Casa Azul, home of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; this is the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx.

For the summer, New York City’s shrine to all things living and green is transforming into a little piece of Mexico in its latest exhibit, Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life.

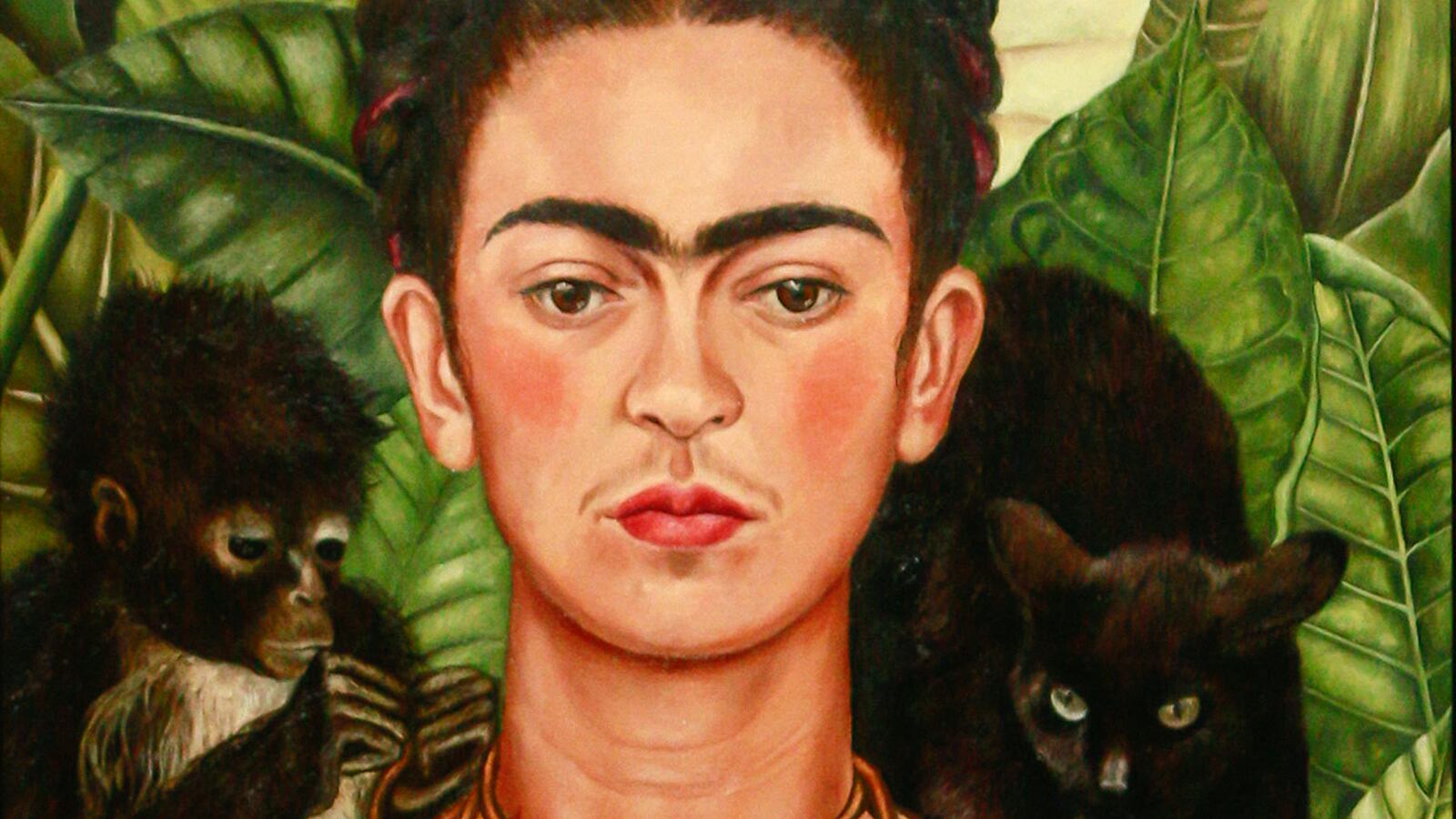

Artist Frida Kahlo, she of the iconic unibrow, traditional Mexican dresses, and intricately braided hair, has become one of the most recognizable faces in art. Since her death at the age of 47 in 1954, a cult-like following has developed around her and the vibrant, wholly original paintings and drawings she created.

It doesn’t hurt that one of her favorite subjects was herself. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone. Because I am the person I know best,” she once said. (It also doesn’t hurt that Salma Hayak depicted the artist in a critically-acclaimed 2002 biopic.)

The cult of Kahlo doesn’t seem to be slowing down anytime soon.

In a recent piece, The New York Times stated that the artist is “having a moment,” which may be a bit of an understatement looking at the sheer number of Frida-happenings in just 2015.

The Detroit Institute of Art opened Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit; a London gallery launched a show of Japanese photographer Ishiuchi Miyako’s photographs of Frida’s clothing and personal effects that were locked away for 50 years after her death; Mirror, Mirror is displaying photographs of Kahlo by various photographers at Throckmorton Fine Art in New York City; a trove of the artist’s love letters to José Bartoli were auctioned off in April for $370,000; and numerous books examining her life and art have recently been published.

It may seem that there isn’t much left to say or discover about the artist, but the New York Botanical Garden is proving that wrong.

Among the Frida-mania, Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life stands out as a fresh approach to studying the artist and the inspiration she found and nurtured in the nature around her.

“We, like many people, knew of Frida Kahlo as one of the most important artists of the 20th century and, dare I say, as a cultural icon. But we as gardeners were completely and utterly unimpressed by those two things,” said Todd Forrest, the Arthur Ross vice president for Horticulture and Living Collections. “When we learned about Kahlo as a pretty sophisticated gardener, we were blown away.”

Often in the story of Kahlo, admirers get caught up in the sensational aspects of her life.

Following a horrific trolley accident at the age of 18, Kahlo lived her too-short life in chronic pain, suffering through over 30 surgeries, forced to wear corsets that looked more like torture devices, even enduring the amputation of one of her legs.

The fallout from this tragedy fueled her art—her pain and emotional suffering is viscerally present in many of her works.

But her physical difficulties couldn’t stop her from leading a passionately vibrant life. Kahlo was a revolutionary in many ways, including her personal life.

Much interest in the artist focuses on her relationship with (and two marriages to) famed muralist Diego Rivera. She also acquired an impressive roster of lovers—both men and women—including Leon Trotsky, Josephine Baker, sculptor Isamu Noguchi, and painter Jacqueline Lamba, the wife of André Breton.

But the NYBG exhibit focuses on the more thoughtful aspects of the artist’s life and inspiration.

Its centerpiece is a “re-imagining” of the garden at the Casa Azul, Kahlo’s birthplace and home with Diego Rivera where the Museo Frida Kahlo is now located.

After Diego paid the Kahlo family’s mortgage on the house in 1930, the couple took ownership. They gradually increased the size of the property and morphed the traditional courtyard and kitchen garden into an oasis of plant life, often reflecting Kahlo’s fierce Mexican nationalism.

“I think that she really wove her Mexican identity throughout her whole life, and much of that identity was things that were obviously native to Mexico, including plant life,” Karen Daubmann, associate vice president for exhibitions and public engagement, tells The Daily Beast. “When you really start looking closely at her, you notice the flowers in her hair. You notice the embroidery on her dresses. You notice the notes she makes in her diary and her sketches. You notice that everything that she paints in her still lifes and her paintings is very carefully selected.”

Walking through the exhibit, visitors are hit with a vibrant explosion of life. It’s hard not to feel the spirit of Kahlo right there with you, surrounded by a diversity of flowers, rainbow of bright colors, and vivid greens of living plants.

Rather than focusing on just the garden during Kahlo’s lifetime, the exhibition explores its many stages—from its early incarnation under Kahlo’s parents, to the carefully cultivated garden of Kahlo and Rivera, to its current incarnation in Mexico City. (For this reason, the exhibits’ creators prefer to think of it as a “re-imagining” of the Casa Azul garden rather than a “re-creation.”)

Placards point out flowers and plants that were important in Kahlo’s life and paintings, like dahlias that the artist used in her hair designs and table arrangements and philodendron leaves that were an important part of Aztec ritual and appeared in her paintings.

The exhibition team called on the help of Scott Pask, a Broadway set designer, to build the more intricate re-creations.

One of Rivera’s additions to the garden was a four-tiered pyramid on which he displayed his collection of pre-Hispanic artwork. The stunning, colorful pyramid lives on in the Bronx, now featuring row upon row of terra-cotta pots (which came from Mexico, but were distressed to look older) with native plants in them (think lots of varieties of cacti).

In one corner, a representation of Kahlo’s studio desk is a delightful surprise, covered with old bottles of paint and palettes and paintbrushes that look as if the artist has just gotten up from her work.

“I had a few minutes to sort of sit in her studio by myself and look out the huge light-filled windows and sort of see what she saw when she was in her studio,” Daubmann says of the trip she and a team from the New York Botanical Garden took to the Casa Azul. “It’s really amazing to be there and to see that she curated this life for herself. And she was homebound for so much of it that she was just really making a place that she felt comfortable in.”

The garden powerfully channels Kahlo, but a fuller picture of the importance of nature to her work can be seen in the 14-piece exhibition of her paintings and drawings assembled by guest curator Adriana Zavala.

Kahlo’s self-portraits are a critical part of her oeuvre, and a few that have deep connections to the natural world are present in this collection. But their popularity often overshadows her other important works, like her carefully chosen still lifes.

Throughout the summer, the New York Botanical Gardens has many other related events planned to celebrate Kahlo and her Mexico, including a residency by Mexican musicians the Villalobos Brothers, textile demonstrations by artisans from Chiapas and Oaxaca, live dance and music events, a Mexican film festival, and more, plus night celebrations where the margaritas and tacos will be flowing.

“I paint flowers so they will not die,” Kahlo once said. Walking through the lush pathways, you sense she would have thoroughly approved of the NYBG giving her garden a second beat of life.