John G. Morris had grown tired of watching the war pass him by. As a photo editor for Life magazine based in London after 1943, he’d seen some dark days as the Nazis’ V1 missiles descended on the city. But in 1944 the tide of battle clearly was turning. The Allies crossed the Channel and invaded Normandy on June 6, and Morris edited the rolls of film shot by his famous friend Robert Capa, including the now iconic photographs—blurred, violent, unforgettable—of the D-Day landing.

Morris was not a photographer. He picked images, he didn’t make them. But, finally, in that summer of 1944, when the fighting was still heavy as the Allies drove inch by inch through the hedgerows and villages on their way to take Paris, Morris told his bosses he was going to see firsthand what was happening. He gave himself a high-sounding title: Photo Coordinator for the Western Front. And he hitched a ride on a transport to France.

Morris took with him a big, clumsy, borrowed Rolleiflex camera that shot 6-centimeter by 6-centimeter negatives, and he managed to get about 15 rolls of film. Over the course of several weeks, he used them all up. He published a couple of photographs in Life, and then he went back to his day job.

Years passed. Then decade after decade. Morris settled into a life of art and activism in Paris, his adopted home, and I am happy to say that at age 97 he’s still going very strong. But it was only last year that anyone got a glimpse of those pictures he took in the summer of ’44. And those who saw them at a major photo show in Perpignan were blown away.

David Douglas Duncan, another American nonagenarian, and one of the greatest war photographers of the 20th century, told Morris he thought the photos were better than Capa’s. “They are composed remarkably, very well chosen. John worked without tricks and without putting himself out front.”

The whole collection has now been published in France in a book lovingly pulled together by Morris’s friend Robert Pledge, with the title Quelque Part en France, or “Somewhere in France,” which is how the American troops and those traveling with them were supposed to identify their location when they wrote home. The text is drawn mainly from Morris’s letters, many of which are reproduced.

As you look through the book, you can’t help but think Duncan was right. The images, some of them on view now at the International Center of Photography in Manhattan, are simply amazing for their ability to put us on the ground there in Normandy and Brittany as the Allies push through.

Morris captured the violence, to be sure. With his huge, clunky camera, he managed to convey the blur of invasion as a tank passes a church. His photograph of a dead American soldier near Marigny is as beautiful and respectful, and moving and horrible, as any I have seen. The body is covered. The helmet is visible above the poncho, leaning against garden shrubbery, and one hand reaches out, the fingers slightly curled and covered with the black grime of war.

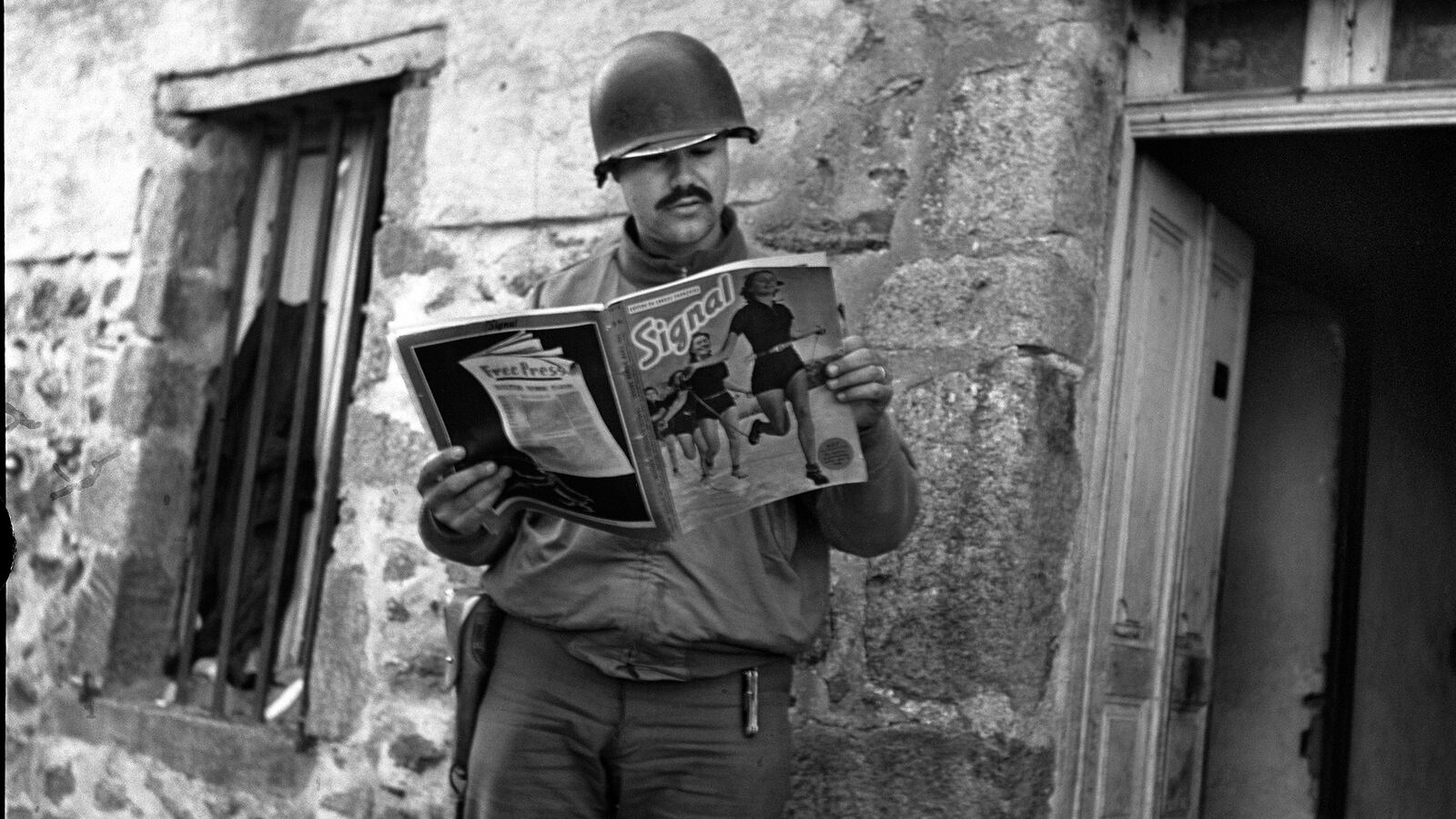

But it’s Morris’s very human and often humorous touch when he’s among the living that is really striking. The expression of a GI browsing a copy of the German propaganda magazine Signal, which liked to feature Aryan bathing beauties cavorting on its covers, is a study in contained, conflicting emotions.

One has the remarkable sense in Morris’s photographs, when looking at the faces of refugees and schoolchildren, soldiers and street vendors, that they quite like the person behind the camera—who becomes, in a sense, you or me. Even a young German prisoner in Brittany, his hands above his head, has an expression that mixes fear, defiance, and little bit of puzzlement.

You may have seen thousands of photographs from World War II, but you have never seen any quite like these.