This is the third article in a three-part series about the way top officials in the fight against terrorism during the 1990s worked closely together to try to keep Americans safe—but turned against each other in the Age of Trump, and why.

In July 2001, several Yemeni men detained by the FBI were discovered to have been taking photographs of the tops of buildings around downtown Manhattan. That was two months before the whole world focused on smoke and flames coming from the top of New York’s tallest buildings, the twin towers of the World Trade Center.

The security concern of that moment concerned another locale in lower Manhattan. New York had become known as the terrorism-trial capital of the world, having seen in its courts the culprits of the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993, the thwarted TERRSTOP case involving the plot to blow up New York City landmarks, and the East African bombings of 1998. All had led to successful convictions. As a result enhanced security was put in place for 26 Federal Plaza, which housed the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service among other agencies, and the nearby federal courts. But now that extra layer of protection had been removed.

John O’Neill, the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) for the New York Field Office’s National Security Division at the time, had an instinct about the danger to New York City. Seeing this Yemeni activity, he asked an FBI agent to write a white paper to send to FBI headquarters requesting resources for continued security. The paper outlined what the FBI believed was a continuing threat to the federal building and the federal courts area. The paper requesting the continuation of security enhancements was endorsed by other occupants of 26 Federal Plaza as well.

A copy of the paper was left for me by the author while I was serving on the Joint 9/11 Congressional Inquiry in 2002. The agent who had written the paper asked if the 9/11 Inquiry could find out if anyone at FBI headquarters had even seen it. All she knew was that the enhanced security never happened. The white paper fell into the black hole of “routine” FBI communications from the field and had extremely limited circulation.

The reaction had been similar in the case of the so-called “Phoenix Memo,” written before 9/11 by an FBI agent in Arizona trying to raise a red flag about the large number of Middle Eastern men enrolled in American flight schools. The agent in Phoenix had worked terrorism cases before, but now that he was in Arizona he was told to stay in his investigative lane, which in Phoenix did not include al-Qaeda. He testified before the inquiry behind a screen to protect his image from being seen, although his name was known.

The Joint Congressional Inquiry predated the independent 9/11 Commission and, as had been predicted by members of Congress who wanted to go straight to an independent commission, it fell prey to politicization.

Days before FBI counterterrorism officials were due to appear before the inquiry, I briefed Rep. Tim Roemer (D-IN), himself a former FBI agent, on the white paper so he could question the new FBI Counterterrorism Division chief, Dale Watson. As the hearing approached, however, FBI Deputy General Counsel Tom Kelley (who had somehow managed to get himself onto the staff of the inquiry to do FBI damage control), talked Roemer and the inquiry leadership out of questioning Watson about it. I had cleared any classification concerns with the FBI, but Kelley managed to put enough doubt in Roemer’s mind to bury the issue.

The 9/11 Inquiry was staffed by personnel from most of the major intelligence agencies. And it soon became apparent that all brought with them, to a greater or lesser extent, the perspective of their agencies, in particular with regard to 9/11. Before the country could move on from the horrific tragedy, it needed someone to blame. I don’t recall exactly whose idea it was, but I suspect it came from the inquiry’s staff director, L. Britt Snider, a former CIA Chief Counsel who himself had written many articles and books on intelligence, but we were all handed a copy of Thomas C Shelling’s preface to Roberta Wohlstetter book Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. It is one of the most brilliant passages ever written about bureaucratic failure:

“Surprise, when it happens to a government, is likely to be a complicated, diffuse, bureaucratic thing. It includes neglect of responsibility but also responsibility so poorly defined or so ambiguously delegated that action gets lost. It includes gaps in intelligence, but also intelligence that, like a string of pearls too precious to wear, is too sensitive to give to those who need it. It includes the alarm that fails to work, but also the alarm that has gone off so often it has been disconnected. It includes the unalert watchman, but also the one who knows he’ll be chewed out by his superior if he gets higher authority out of bed. It includes the contingencies that occur to no one, but also those that everyone assumes somebody else is taking care of. It includes straightforward procrastination, but also decisions protracted by internal disagreement. It includes, in addition, the inability of individual human beings to rise to the occasion until they are sure it is the occasion–which is usually too late.”

It took only three weeks for the Senate’s leading snake-oil salesman, Senator Richard Shelby (R-AL), to politicize the inquiry. His target was the aforementioned inquiry staff director, Britt Snider. Before the inquiry had even begun its work, we were informed that Britt had been forced to step down by Shelby and other Republicans. In an act of appeasement so that the inquiry would not be further delayed, the Democrats acquiesced.

There were all sorts of reasons given for Snider’s departure—mostly that Shelby felt Snider was too close to CIA Director George Tenet. Another reason was that Snider reportedly had failed to inform inquiry members that one of his staff hires was still under the cloud of an “unresolved” polygraph examination. (A fairly common occurrence in the intelligence world and in no way dispositive of any guilt.) When Shelby met with inquiry staff, he provided no reason. “If this inquiry is going to be politicized, it will have no credibility,” I told Shelby before the entire staff. He denied any politicization.

Ironically, Snider had been unanimously confirmed to the position of CIA General Counsel by the Senate Intelligence Committee—chaired by none other than Richard Shelby—just four years earlier. They did so citing Snider’s excellent reputation and integrity.

But now, with the inquiry into 9/11 about to start, the Republicans saw their job as doing damage control for the George W. Bush Administration. Republicans on the inquiry didn’t want anyone in charge who was too close to CIA Director George Tenet—a Clinton appointee who might be needed to take the fall for 9/11. Even worse, both Tenet and Snider had been Clinton appointees. Shelby would have none of it. Tenet had agreed to stay on as Bush’s CIA director, but he was not totally trusted by Republicans. (It may have been Tenet’s desire to stay in good stead with the Republican administration, and keep his job at the CIA, that led him to his “slam dunk” remark a year later about the certainty Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, even though it did not.)

Snider’s replacement was the less politically controversial Eleanor Hill—a former Clinton-appointed inspector general for the Department of Defense. The Democrats were satisfied.

While Snider was open and accessible, Hill’s management style was to spend entire days behind a closed door huddled with just a few chosen staff. (I don’t recall her ever having one meeting, or just a chat, with the entire staff.) One reason for the secrecy centered around what would become known as “the 28 pages”—the classified final section, Part Four, of the inquiry’s report which dealt with the alleged connection of certain Saudi government officials to 9/11 hijackers. This section (actually 29 pages) would not be declassified until 2016, that is, 15 years after the event.

There was little doubt in anyone’s mind at the time, even without fully knowing the specific contents of the 28 pages, that the decision by the Bush Administration to classify this section of the 9/11 Inquiry’s report was not only to protect the Saudi royal family, but one man specifically—Bush family friend Prince Bandar bin Sultan.

Moreover, President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney were setting their sights on a war to overthrow the Saudis’ neighbor in Iraq, Saddam Hussein, and bad publicity about Saudi relations with al-Qaeda would be, at best, a distraction. Public opinion already was hostile to Riyadh since 15 of the 19 hijackers on September 11, 2001, were in fact from Saudi Arabia.

The 28 pages ultimately did not expose the cloak and dagger drama their secrecy led people to anticipate, but they did show, for example, some shadowy telephone linkages between al-Qaeda operative Abu Zubaidah and a security guard at the Saudi Embassy in Washington as well as with the unlisted number of a company managing the residence of Bandar in Aspen, Colorado.

Two of the 9/11 hijackers, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, revealed to an FBI informant that they had received aid from an al-Qaeda supporter living in San Diego prior to 9/11, but it could not be firmly established that their benefactor had received funds directly from the Saudi government. A man living across the street from the hijackers claimed he gave them support, and the long-classified Part Four of the 9/11 inquiry noted cautiously (page 417) that he “reportedly received funding and possibly a fake passport from Saudi Government officials,” before stating flatly, “He and his wife have received support from the Saudi Ambassador to the United States [Bandar] and his wife.”

None of this was probative, but all of it would have cast serious suspicion on a diplomat so close to the president’s family he often was called “Bandar Bush.” (Bandar remains an influential figure in Saudi Arabia. Riyadh’s current ambassador to the United States is his daughter.)

It was also argued at the time that the FBI was still investigating this thread of evidence, and thus the need for secrecy. But with the Saudi relationship deemed so fragile and essential, even President Barack Obama’s press secretary would say at the time of the 28 pages declassification, “This information does not change the assessment of the U.S. government that there is no evidence that the Saudi government or senior Saudi officials funded al Qaeda.”

The major reforms the intelligence community hoped to achieve after 9/11 focused on the removal of “stovepipes” to create horizontal intelligence structures within intelligence agencies and across the intelligence agencies. It could be argued that by creating at least three new enormous bureaucracies, the stovepipes didn’t go away, but just got bigger—namely the new Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), and of course, the biggest one of all, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

And while the FBI still couldn’t bring its computer systems up to date (spending millions of dollars and years on promises only to have vendors admit they had failed), a state-of-the-art National Counterterrorism Center was built in McLean, Virginia. In 2003, I watched on the closed circuit TV in my office as President George W. Bush talked about the effort to unite the country’s foreign and domestic counterterrorism efforts under one roof. Essentially, the FBI’s Counterterrorism Division was being moved to the NCTC. Standing behind Bush 43 was George Tenet, the CIA director.

“Look at that,” I said, believing the positioning of the CIA director behind the president at FBI Headquarters was significant. "The Bureau just lost its Counterterrorism Division to the CIA.”

In those post-9/11 days, agencies in Washington were watching carefully to see who the winners and losers would be. FBI agents would now be sitting in Fusion Centers at NCTC in Virginia next to CIA, DHS, DOD, and other agencies, and there was no doubt, CIA was packing the NCTC and the ODNI with its people. But CIA lost something as well. Under the new reforms that created the ODNI, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) would no longer be the principal intelligence advisor to the president. That job was now going to the new Director of National Intelligence (DNI).

The biggest post-9/11 reorganization would be the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which brought together 22 separate agencies under one director. But from the beginning, DHS received no love from Congress or the Executive Branch.

DHS headquarters was set up in a run-down World War ll-era former Naval facility on Nebraska Avenue in Washington, D.C. I worked there for nearly three years. Brown water came out of the faucets and putrid air circulated in each of the barracks-like buildings. This space was referred to as the “temporary” home of DHS year after year until finally they moved in 2019 to their new location in Southeast, the St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital complex renovated at a cost of $5 billion. Also worthy of note: there have been four directors of DHS in the three years Trump has been president.

In its early years, DHS was staffed mainly by former military personnel who, in turn, got their military buddies government or contracting jobs there. I personally left the FBI for a six-figure contracting job at DHS, being hired after only a brief telephone interview. The gravy-train of post-9/11 contracting money was flowing freely.

But instead of making the nation’s counterterrorism effort more “lean and mean,” there was now only more confusion. Who was responsible for domestic terrorist threat reporting and pushing that information out to state and local law enforcement? DHS headquarters initially was envisioned as the “clearing house” for homeland terrorist threat reporting. But the information was at FBI, CIA, ODNI, and NCTC. Meanwhile, at the FBI, each field office was mandated to produce a certain number of IIRs (Intelligence Information Reports) every month. Many field offices struggled to come up with something to report back to headquarters and meet their quota.

When FBI agents feel they have to go on fishing expeditions to come up with something—anything—to report back to headquarters, it invites potential abuse. I didn’t hang around long enough to know what became of that program.

Tom Ridge, the former governor of Pennsylvania, was appointed by Bush 43 as DHS’s first director. He was succeeded after only two years by Michael Chertoff, a Harvard Law graduate and former Assistant U.S. Attorney General.

Chertoff had gotten his big break in 1983 when he was hired by—wait for it —Rudy Giuliani, to be a special prosecutor in the Southern District of New York (SDNY). At SDNY Chertoff joined Giuliani and Louis Freeh working on major mafia and political corruption cases. (In later years, he had also worked as a special counsel on the Senate Whitewater Committee, but Chertoff publicly endorsed Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump in 2016, breaking with his former SDNY colleagues.)

As a new federal agency, DHS failed its first major test during Hurricane Katrina. As part of this new gigantic bureaucracy, FEMA was stymied by an unclear chain of command on the ground, and the image out of New Orleans of President Bush congratulating FEMA director Michael Brown for doing “a heck of a job” after hundreds of deaths (the final toll would be 1,833) was politically very damaging.

The major story out of Katrina was that for all the investigations, reforms and supposed “lessons learned” after 9/11, the country was still woefully unprepared to deal with an unexpected, catastrophic disaster. The problem may have been that each and every reform that occurred at each and every agency was now geared toward one major threat—al-Qaeda.

“What happens when al-Qaeda no longer exists? What do we do with all of this? What about other threats?” I asked these questions at one CIA conference. The audience looked at me as if I had just landed from Mars.

Louis Freeh retired as FBI director in June 2001 and Robert Mueller took over. One of Mueller’s first moves was the sudden removal of the FBI’s highest ranking female, Sheila Horan—a 28-year veteran of the agency—from her position as acting chief of the National Security Division. It was apparently during a testy encounter with Mueller over a Chinese espionage case that he exiled her to an administrative position.

If the FBI was behind the curve on the al-Qaeda threat, it was light years behind on the Chinese espionage threat. Its attempts to prosecute Los Alamos scientist Wen Ho Lee for allegedly pulling an Edward Snowden-type download of classified information on nuclear technology that supposedly found its way to China proved how difficult espionage cases were becoming.

This was not the old Russian tradecraft—leaving documents at a dead-drop and getting an envelope full of cash in return. American scientists were wined and dined at scientific and technological conferences in China and throughout Asia. They enjoyed bragging about their work and the free flow of ideas with other foreign scientists. Much of what is published in highly technical journals is, by intelligence community standards, surprisingly sensitive. The culture scientists operate in, and want to keep operating in, is open and cooperative. This makes it very difficult to ascertain malicious intent.

The Feds bearing down on the scientists' colleagues at Los Alamos, attempting to gain access to their computers, shook them to the core. When I took Senate Intelligence Committee staffers to the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the resentment by the scientists for coming under such scrutiny, being interrogated, and the notion that they were expected to monitor their colleagues for possible security violations, was palpable. At the time, they were truly in their own little world with little understanding of Chinese espionage tradecraft.

But the FBI was also in the dark, and they knew it. There had been little doubt that the Chinese had developed a nuclear warhead similar to what’s known as a W-88. Lee came under suspicion for attending conferences in his native Taiwan and being warmly greeted by Chinese counterparts. It was also discovered from some old Bureau wiretaps that Lee had phone conversations with a convicted Chinese spy back in the '80s. Lee was arrested and held in solitary confinement for 10 months.

Numerous congressional hearings were held before the Intelligence Committees, the Energy Committees, and the Armed Services Committees. Members pounded their fists on the table, asking how the FBI could let this happen. Ultimately, over the ensuing months, the case faltered and media opinion—as well as congressional opinion—started to turn in Lee’s favor. His image went from that of diabolical traitor to a victimized and misunderstood Taiwanese immigrant who had been harassed and badly mistreated by the U.S. government.

No definitive case could be made against Lee, the technology behind the W-88 had been in the public domain, and the public relations aspect was a disaster for the Bureau. Attorney General Janet Reno had given the order to Louis Freeh for the FBI to pull the plug on the case. Several media outlets paid Lee $1.6 million for leaking his name and damaging his career—as had been done for Richard Jewell, wrongly accused in the Atlanta Olympics bombing. But to this day agents who worked on the case believe Lee was probably “good for it.”

Tensions in the Counterintelligence Division were high, and Mueller’s removal of Horan over a case concerning a possible recruitment attempt by the Chinese of an American citizen frayed agents' nerves. Mueller was a hard-nosed, no nonsense legal eagle. While the Counterterrorism Division was waiting for the next shoe to drop—and they were certain al-Qaeda had more plans for the U.S.—it turned out the Counterintelligence Division— yes, the Counterintelligence Division—had had Robert Hanssen in its midst for 10 years undetected.

The FBI knew Soviet spycraft well, not so much when it came to the new Russia. And when it came to Chinese espionage, with the Chinese willing to play the long game and thousands of Chinese students, scientists, academics pouring into the U.S. to work and attend school, it was an enormous undertaking to detect espionage activity.

The Chinese intelligence operatives were known for reaching out to Chinese nationals in the U.S. and appealing to their nationalism. The Chinese were subtle, not as heavy handed as the Russians, and thus left few clues to follow. And this wasn’t only in the area of human intelligence, which the Russians excelled in for decades, but in economic espionage and cyber intrusions, which were Chinese specialties.

The Chief of the East Asia Counterintelligence Unit invited me to leave the Congressional Affairs Office and come work for him. “The Chinese have totally penetrated our military,” he told me in a pique of stress and exasperation.

Chinese espionage, both in terms of economic and technological espionage, remains one of our country’s most intractable problems. Our failure to thwart Russian cyber-manipulators in our own presidential election has not been lost on the Chinese who see what naive, easy prey we are. Also not lost on the Chinese is the Senate Republicans’ refusal to even pass legislation to address the issue, and worse still, recite in unison the Russian narrative that it was Ukraine and not Russia who infiltrated our democratic process. The Chinese surely look on in amazement as they see the United States not only is not addressing the issue of cyber penetration by foreign actors, but actually seems to be wittingly enabling it.

As part of Mueller’s reorganization of the Bureau’s intelligence apparatus, he hired Maureen Baginski, the former signals intelligence director at the National Security Agency. Baginski would become Executive Assistant Director of Intelligence, somewhat modeled after the ODNI where all intelligence and intelligence product would flow through her. Hiring Baginski was essentially a way for Mueller to demonstrate he was reorganizing the Bureau’s intelligence function. Especially after 9/11, the key to every agency’s survival was “reorganization.” She made her dutiful rounds around town and on the Hill was heralded as “the woman who would save the FBI.” She hired me as her special assistant. The senior agents resented her.

As Mueller’s golden girl they would tolerate Baginski, at least at first, but agents were very resistant to being supervised in any way by a non-agent. “There are two kinds of people at the FBI,” I was told on my first day at the Bureau. “Agents and furniture.”

Baginski’s management style had not won her many fans at the NSA—and I had been warned. She lived on cigarettes and Diet Coke, was always high-strung, and thought FBI agents were out to get her. They were.

In the end, Baginski lasted only two years in her position. Mueller, helping her make a gracious exit, announced she would become a “senior adviser” to the FBI. She had started her intelligence career as a Russian linguist and was an analyst at heart, not a bureaucrat, and she was supportive of the Bureau’s non-agent intelligence analysts and “case support” workers (Intelligence Operations Specialists), a cadre at the time in serious need of professionalization.

After 9/11, the discovery that many of the Bureau’s intelligence operation specialists were untrained former administrative staff without college degrees who couldn’t find Afghanistan on a map showed the public what the rest of the Intelligence Community had already known about the FBI.

The Bureau set as its goal the professionalization of its cadre of analysts and provided them with the same level of training as other analysts in the intelligence community received. Every intelligence analyst would now be required to take a six-week course at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia.

Eighteen years after 9/11, U.S. policy in the Middle East is still closely tied to Saudi Arabia. The Trump Administration has deepened these ties with platitudes, weapons sales, troops, and our assistance to the Saudis’ war in Yemen. But it’s also Trump’s personal financial interests that draws him to Saudi Arabia. As he told a rally in 2015, “They [the Saudis] buy apartments from me. They spend $40 million, $50 million. I make a lot of money from them.” His first trip abroad was to Riyadh. You may remember the sword dance and the hands on the glowing globe.

Historically, American presidents have felt the need to keep Saudi Arabia as one of its closest allies in the region—to keep oil flowing, and, after 1979, to be a bulwark against the Iranian Revolutionary regime. In times of heightened conflict, like the run-up to the war in Iraq in 2003, the Saudis could turn on the oil taps enough to keep prices stable. But the Trump Administration has taken the relationship to such sycophantic levels that the Saudis now believe they can act with near total impunity.

The most glaring example is the Trump Administration’s failure to respond forcefully after the Saudis’ role in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi became clear. The president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, has established a very close relationship with MBS, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the power in front of his father’s throne. Trump built many of his positions on the Middle East around MBS advice and assurances.

In the eyes of the rest of the world, these relationships will make the U.S. complicit in anything the Saudis should decide to do or stumble into. Historically, our relationship with the Saudis has not only fueled Sunni extremist resentment toward the United States, but Iranian-backed Shi’a resentment as well.

When imprisoned fighters from the so-called Islamic State were reported escaping from the Kurdish region of northern Syria after the recent capricious U.S. withdrawal, President Trump remarked, “Well they are going to be escaping to Europe, that's where they want to go. They want to go back to their homes.”

But, while some of those captives might have made that argument from prison, it’s probably not true for the most dangerous among them. What the intelligence community knows is that those mujahideen fighters who went to Afghanistan from Europe and the Middle East in the '80s did not return home in the '90s. They went to North Africa, Yemen, Pakistan, or remained in Afghanistan, continuing to direct and spread their notion of jihad.

So once again there is a false narrative being fed to Americans by the current president that the terrorist threat is “over there,” and that our relationship with the Saudis will make the Middle East and the U.S. safer.

You would think, after all these years, we had learned otherwise. But none of it is surprising knowing how little Trump listens to his intelligence agencies, and knowing how little he thinks of the FBI. At some point, his unwillingness to listen to something other than his own voice will have implications for the security and safety of Americans.

After leaving the FBI, Louis Freeh, his Chief of Staff Bob Bucknam, and his congressional liaison guru John Collingwood, all ended up working together at MBNA, the credit card company in Delaware, Maryland. (MBNA was later purchased by the Bank of New York.) Freeh had signed on to Giuliani’s unsuccessful 2008 presidential campaign.

But more recently Freeh, who now operates The Freeh Group, registered as a foreign lobbyist working not only with Giuliani, but law professor Alan Dershowitz, who has become another Trump mouthpiece. Dershowitz was ensnared in the Jeffrey Epstein scandal and hired Freeh’s security company to conduct an “investigation.” Perhaps it's not a surprise that the investigation cleared Dershowitz of any foul deeds.

While Giuliani was involved in his now well-known escapades involving Ukraine on behalf of Donald Trump, he was also working with Freeh representing a Romanian-American real estate investor named Gabriel Popoviciu who was trying to beat his conviction for corruption in Romania. An appeal ultimately failed, and Popoviciu was sentenced to seven years in jail. Another U.S. attorney who traveled to Romania in 2016 to assist in attempts to clear Popoviciu, working toward the same goal as Giuliani and Freeh, was—wait for it—Hunter Biden, the son of then-Vice President Joe Biden.

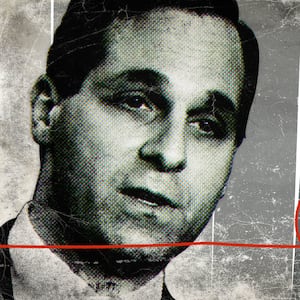

With the unexpected ascendency of Donald Trump to the presidency, the paths of Rudy Giuliani, Louis Freeh, and James Kallstrom diverged sharply from those of James Comey and Robert Mueller. Giuliani, Kallstrom, and Freeh remained connected by their anti-Hillary beliefs and spoke out against her at every opportunity. Comey and Mueller would find themselves, reluctantly, dragged into Trump’s reality show while trying to do the right thing in an environment that made that nearly impossible. They would always be in a no-win situation.

Like Freeh and Kallstrom in particular, William Barr had been another life-long fanboy of George H.W. Bush, having first worked with him when they were both at the CIA. Barr worked on the elder Bush’s presidential campaign in 1988 and was later appointed to head the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel. When Bush 41 became president, Barr was appointed attorney general.

From that first job at DOJ in the Office of Legal Counsel, Barr was the champion of robust executive authority. He spoke about it, wrote legal and academic opinions about it, and misused the Constitution to defend the president in everything from Iran-Contra to increased surveillance techniques and incarceration of asylum seekers. He’s defended Trump’s Muslim ban and child separation policies at the southern border. When the courts differ with him, he denounces the courts. When his own DOJ Inspector General disagrees with him on the Russia Inquiry, he trashed his own department’s Office of Inspector General.

Although Trump did not know him, it was Barr’s career-long record of fighting for an all-powerful, unaccountable executive that convinced Trump that Barr was the right guy to be his attorney general. Not since Trump bemoaned, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?” has Trump been so convinced he finally found the right guy.

Comey tried to stay one step ahead of an organization that contained forces he could not control while answering to a president pressuring him to obstruct justice. Robert Mueller has been criticized for not dealing the death knell to the Trump presidency that The Resistance had hoped for, even though his work as Special Counsel has led to the convictions of at least half a dozen Trump associates.

But it was always obvious, from the moment Trump fired his first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, for recusing himself from the Russia investigation, that Trump had wanted Mueller stopped.

Barr and Rod Rosenstein, the deputy AG, knew Mueller and understood that the American public respected his reputation. Firing Mueller would set off a political firestorm. Mueller had been the longest serving FBI director since J. Edgar Hoover. He knew how to survive and was a cautious, methodical man. He did not seek the spotlight, and he was not prone to hyperbole. These may be the reasons he would be allowed to continue his work, and Mueller, in return, would respect the boundaries he was expected to observe.

There would be no sworn testimony by Trump before the Special Counsel, as Trump was such a pathological, often delusional liar, he would surely incriminate himself. The same would be true for Trump’s son, Donald Trump Jr. There would be no indictment of a sitting president. In the end, Mueller’s report laid out the different ways Russia interfered in the 2016 election and the Trump campaign’s receptivity to Russia’s overtures—without calling it “collusion.”

More damning were the attempts to obstruct justice, as outlined in Part 2 of the report. But Barr, taking a page from the classic “influence operation” playbook often employed by authoritarian regimes, knew the first thing people hear is what sticks in the mind. He got out in front of the cameras before the report was even released to Congress, and claimed it exonerated Trump—repeating the mantra, “no collusion.”

It would be up to the Democrats now to scramble, to go on the offensive, to look like they were indeed on a “witch hunt.” The plan worked, and a public already weary of the Russia story, and very unlikely to read the report’s 448 pages, mostly accepted that the case was closed.

None so blind as those who will not see. Mueller had held a press conference when the report was released stating, “I will close by reiterating the central allegation of our indictments—that there were multiple, systematic efforts to interference in our election. That allegation deserves the attention of every American.” When he finally testified before Congress, he said about Russian interference in our elections, "They are doing it while we sit here. And they expect to do it during the next campaign."

And yet, today, Republicans in Congress and members of the Trump Administration are deliberately, consciously and employing an influence operation directed by the White House to accuse Ukraine, not Russia, of the interference. The question yet to be answered: Who is directing the White House?

It is possible the ramifications of the Mueller Report for Donald Trump may not have been fully realized yet as the multiple attempts to obstruct justice it outlines could become an article of impeachment.

But what to make of Giuliani, Kallstrom, and Freeh’s continued hostility toward the Clintons for their supposed criminality while so publicly defending a man whose personal lawyer and “fixer,” Michael Cohen, called him a “racist, con man, and cheat” before Congress, providing them copies of checks Trump used to pay off a porn star.

Donald Trump seems to get a pass when it comes to the standards of morality each of these three—Giuliani, Kallstrom, and Freeh—claims to practice as part of their Catholic faith. Each of them understands the law, and when in their prime, enforced it. They especially understood criminal organizations and how they operated. But by keeping the focus on Hillary Clinton and all that “lock her up” chanting, Trump supporters don’t have to face the reality that far more Trump associates have gone to jail than Clinton associates.

When Trump’s world comes crashing down from the weight of his illegalities—as inevitably it will—those Fox News appearances by Giuliani and Kallstrom, especially, will be played in a loop, tarnishing their legacies.

There was an expression the FBI used when pursuing the most difficult cases—an expression each of these men is familiar with—“However long it takes.”