George Clooney hates the paparazzi. But he also knows the power of a snapshot. So the Oscar winner just launched a privately funded satellite to broadcast pictures of troop movements throughout Sudan. He’s now back from a visit to the genocide-ridden country, which in January voted to split itself in two, making Southern Sudan the world’s 193rd nation. Clooney’s dogged activism in Africa has earned him the ear of the U.S. foreign-policy establishment. Twice, he’s visited President Obama in the Oval Office. In his next movie, The Ides of March , Clooney plays a flawed presidential candidate. Does he dream of becoming the real thing? “I didn’t live my life in the right way for politics, you know,” he tells Newsweek . “I f---ed too many chicks and did too many drugs, and that’s the truth.”

Clooney also has hard words for fellow celebrities who overexpose themselves: Twitter-loving Hollywood stars need to shut up. The actor says. “You shouldn’t be telling them what you’re thinking when you’re sitting on the toilet. Clooney’s outsize role as celebrity-statesman has earned him critics. Says one Africa expert, “The success in South Sudan happened in spite of celebrities, not because of them.”

And yet one former “Lost Boy,”—the protagonist of the bestseller What Is the What? —says that the referendum in Sudan would not have happened without the star. “He saved millions of lives. I don’t think he knows this,” says Valentino Achok Deng. Read the full story below.

As Hollywood scrambles through the final days of jockeying for Oscars, George Clooney’s attention is far away—9,000 miles away, to be exact. The veteran Academy Award campaigner plans to walk the red carpet and crack open an envelope at Sunday’s ceremonies, but he has no movie in contention. A different drama is on his mind.

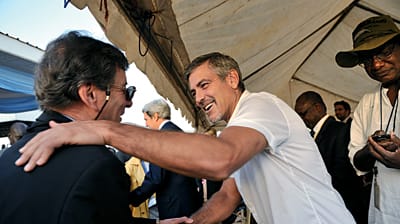

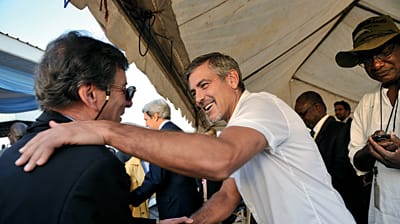

In January, Clooney was back in South Sudan, directing his star power toward helping its people peacefully achieve independence from the northern government of Khartoum after two decades of civil war. With five years’ involvement in Sudan, Clooney has begun to define a new role for himself: 21st-century celebrity statesman.

Gallery: Saint George

It’s an ambitious avocation: Clooney has been leveraging his celebrity to get people to care about something more important than celebrity. South Sudan’s January referendum for independence was quickly followed by uprisings that toppled North African and Arab dictatorships, with power moving away from centralized political bureaucracies and toward broader popular engagement. In this new environment—fueled by social networking—fame is a potent commodity that can have more influence on public debate than many elected officials and even some nation-states.

“My job is to amplify the voice of the guy who lives here and is worried about his wife and children being slaughtered. He wants to shout it from the mountaintops, but he doesn’t have a very big megaphone.”

“It’s harder for authoritarian regimes to survive, because we can circumvent old structures with cellphones and the Internet,” says Clooney. “Celebrity can help focus news media where they have abdicated their responsibility. We can’t make policy, but we can ‘encourage’ politicians more than ever before.” Which was why, a few weeks ago, Clooney was being driven in a white pickup down a red dirt road under the watchful eyes of teenage soldiers armed with AK-47s. L.A. was half a world away, but the paparazzi were not far from his mind. “If they’re going to follow me anyway,” he was saying, “I want them to follow me here.”

Clooney had traveled to the oil-rich contested region of Abyei on the eve of South Sudan’s historic referendum. When the polls closed seven days later, Africa’s largest nation would be divided into two separate countries by electoral mandate. After witnessing more than 2 million people murdered—including the first genocide of the 21st century, in Darfur—South Sudan would finally be on the path to independence. It was an outcome that even three months earlier appeared unlikely. And Clooney, according to many observers, played a pivotal role.

No one in Abyei has seen a George Clooney movie. His credibility here comes from the multiple trips to Africa, many of them with John Prendergast, cofounder of the Enough Project. Amid the factions, Clooney is seen as a man unconstrained by bureaucracy, with access to power and the ability to amplify a village’s voice onto the world stage.

Celebrity statesmen function like freelance diplomats, adopting issue experts and studying policy. More pragmatic than stars-turned-social activists in the past, they use the levers of power to solve problems. Clooney has Sudanese rebel leaders on speed dial. He’s had AK-47s shoved in his chest. And when he’s on movie sets, he gets daily Sudan briefings via email.

Now he’s gone one step further—George Clooney has a satellite. Privately funded and publicly accessible (SatSentinel.org), this eye in the sky monitors military movements on the north-south border—the powder keg in a region the U.S. director of national intelligence described a year ago as the place on earth where “a new mass killing or genocide is most likely to occur.” “I’m not tied to the U.N. or the U.S. government, and so I don’t have the same constraints. I’m a guy with a camera from 480 miles up,” Clooney says. “I’m the anti-genocide paparazzi.”

Clooney’s high-wattage visits draw unwelcome attention to the head of the north’s Islamist government in Khartoum, Omar al-Bashir, who has been indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court. News of the satellite spurred Khartoum to issue a press release accusing Clooney of “an ulterior motive that has nothing to do with peace.” But to the world media, a press release is no match for the spectacle of Clooney in Africa.

Clad in a khaki-colored ExOfficio vest, white safari shirt, lightweight pants, and worn hiking boots, Clooney doesn’t look or act like a buttoned-up diplomat. Skinnier and slightly shorter than he appears on film, his face tanned, and a salt-and-pepper goatee growing in, he will be 50 in May and has the attitude of a man determined to spend his time on things that matter. “The truth is that the spotlight of public attention is lifesaving—whether it’s a genocide, disease, or hunger,” says New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof. “Stars can generate attention and then generate the political will to do something about a problem.”

Clooney read Kristof’s Darfur columns in 2005. “I had just come out of Oscar season—I had two movies up—and you really do campaign, like kissing babies,” he says. “So by the time it’s over, you sort of feel unclean. You want to do something that makes you feel better.” He remembered how his father, Nick—a newsman from Kentucky—had been furious when international stories were bumped by celebrity gossip. So when he made his first trip to Sudan with his father, Clooney was determined to put the candy coating of celebrity on the serious substance of foreign policy.

But he quickly learned the dangers of just dropping in on a humanitarian crisis: As a way of giving back to a refugee village where he and his father stayed, he donated money to build a well, huts, and a community center. “A year later, the next-door villagers—who wanted water and needed shelter—ended up killing some of the people to get to that well and to get to that shelter,” Clooney says, his voice trailing off. “It’s devastating. Your response is… to continue to try to help, but we have to be very careful—and sometimes helping is not throwing money at a problem.”

John Prendergast gets credit and/or blame for popularizing the actor-activist alliance. A former director of African affairs at the National Security Council under President Clinton, Prendergast lopes around sporting sneakers and graying shoulder-length hair. He stumbled on the formula after a trip with Angelina Jolie to the Congo in 2003 drew people’s attention. Prendergast’s partnership with Clooney builds on the template set by U2’s Bono and Jeffrey Sachs of the Earth Institute, who publicized efforts to alleviate extreme African poverty through debt forgiveness and targeted aid while successfully lobbying the Bush administration to expand funding for AIDS drugs.

“Bono’s model really worked,” Clooney says. “There is more attention on celebrity than ever before—and there is a use for that besides selling products.” Stars like Brad Pitt (Katrina), Ben Affleck (Congo), and Sean Penn (Haiti) followed suit. “A lot of the young actors I see coming up in the industry are not just involved, but knowledgeable on a subject and then sharing that with fans,” says Clooney. No one’s just a “peace activist” anymore—they have a specialty.

Clooney’s focus on Sudan has made him a resource for top policymakers, who also benefit from the attention he brings. He has briefed the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the U.N. Security Council. And it helps that the American president is a friend. Clooney and Barack Obama, both born in 1961, first worked together on Darfur. After their first Oval Office meeting, Obama appointed a special envoy to Sudan. The second meeting, last October, resulted in the deployment of Sen. John Kerry to Khartoum. “When the klieg lights go off, he is willing to maintain attention and work with policymakers across partisan lines,” says conservative Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback. “These guys have spent more time on the ground in Abyei than most American officials have,” Kerry says of Clooney and Prendergast. “The White House has been listening to them.”

Clooney plays a flawed presidential candidate in his next film, The Ides of March. He’ll direct the movie he co-wrote, giving his character lines he’d like to hear from a presidential candidate. But despite occasional overtures from the California Democratic Party, Clooney has rejected the constraints of conventional politics. “I didn’t live my life in the right way for politics, you know,” he said, sitting outside the Central Pub in Juba, scarfing down pizza. “I f--ked too many chicks and did too many drugs, and that’s the truth.” A smart campaigner, he believes, “would start from the beginning by saying, ‘I did it all. I drank the bong water. Now let’s talk about issues.’ That’s gonna be my campaign slogan: ‘I drank the bong water.’ ”

Off-camera, Clooney is funny and friendly, frenetic and unpretentious. He’s proud to be “the son of a newsman.” He’s decidedly a guy’s guy—a connoisseur of the practical joke and a rubber-faced raconteur, fueled late into the night by vodka and soda. But Clooney is also the first one up in the morning, needing only four hours of sleep. He gives the impression of someone who takes his work seriously, but not himself.

Clooney’s strategy for public diplomacy is informed by film. “You have to get people in the theater first,” he reflects. “The trick is to be really concise—it’s a one-liner on a poster, right? You have to make it clear. ‘You can stop a war before it starts’ [or] ‘If you had a chance to prevent the next Darfur, what would you do?’ ”

“You cannot sustain people’s attention seven days a week, for a long period of time. Actors have an advantage, because you do a movie and then you disappear for a while,” he says. “That’s what John and I try to do—come back every three or four months with something new to reignite interest.” Then he jokes it might take The Real Housewives of Sudan to keep Americans’ attention.

After driving across arid plains dotted with huts and red acacia trees, we pull into a compound guarded by soldiers manning a jeep crowned with a machine gun. Inside a thatched hut, the Abyei administrator, Deng Arop, and the chief of the Ngok Dinka tribe, Kuol Deng, greet Clooney warmly and gesture for the group to sit. “Our job is to ask you how we can help,” Clooney says—and then he listens.

Morale is low and tensions are running high with the neighboring nomadic Misseriya tribe, who are considered an ally of the north. There is talk of the Ngok Dinka declaring an independent association with the south, which could spark a new civil war. Over two hours, Clooney and Prendergast counsel calm and promise to communicate Abyei’s concerns to the southern capital of Juba and to Washington. Then Clooney steps outside to find camera crews from CNN and SkyNews. Alerted that he was heading for Abyei, the networks dispatched cameras to an area without pavement or plumbing, 550 miles from the nearest city.

We drive on to a “returnee” camp known as Mejak Manyore. There, in a field of mud, are rooms without walls. Bed frames, tables, and chairs are arranged almost as if still inside the houses their owners once inhabited. They belong to a handful of the 40,000 families who left the north and returned home to the south over the past four months in anticipation of independence. Now they are living under the open sky in a no man’s land, surrounded by all their earthly possessions. Barefoot children follow Clooney around, alternately friendly and shy, some carrying visibly sick younger siblings in their arms.

“They’ve packed everything up and come here—not out of fear, but out of incredible hope,” Clooney says, surveying the scene. “I’ve been to a lot of refugee camps where people have come because half their family was killed. These people are here because they want to be part of something historic. They believe things are just going to work out.” But two miles away, Misseriya militias attack a Ngok Dinka village that day, killing more than 30 members of the tribe—including police officers—before being repelled and losing more than 80 militiamen themselves.

Clooney’s bed that night is a cot in a compound where relief workers in Abyei live. Perched on plastic furniture, he drinks a warm can of Heineken as the sun sets over a rubble-strewn courtyard. “These guys have a day job that pays them nothing and is dangerous. My day job pays very well, and the worst thing that happens is you get some bad food from craft service,” he says. “I walk an uneasy line trying to bring focus to what they do, because there’s a lot of self-congratulatory crap that makes you sick to your stomach.”

Clooney’s celebrity-statesman strategy has its share of critics on the right and left. Prof. William Easterly of New York University, author of The White Man’s Burden, says “the success in South Sudan happened in spite of the celebrities, and not because of them … It’s unclear why we want celebrities to be in a diplomatic role. It’s like getting someone who’s trained to be an actor or a rock vocalist and having them fix a nuclear-power plant.”

But as recently as October, there was deep pessimism among diplomats and the people of South Sudan that the referendum would occur. The turnaround cannot be ascribed primarily to Clooney’s bully pulpit. The government-in-waiting of South Sudan, led by Salva Kiir, kept its coalition together; the Obama administration and U.N. found new diplomatic focus in the fall; and China—Sudan’s largest oil investor—changed the equation by belatedly announcing it would support the referendum. As the Council on Foreign Relations’ James Hoge cautions: “Celebrities can be a catalyst for policy changes, but the policy changes themselves actually have to come from political figures.”

Still, after Clooney launched a media blitz to mark 100 days to the referendum, English-language newspaper, magazine, and website mentions of the Sudan referendum spiked from six to 165 in one month. Between October and January, the referendum was mentioned in 96 stories across the networks and cable news—with Clooney used as a hook one third of the time. In that same period, 95,000 people sent emails to the White House demanding action on South Sudan. Valentino Achak Deng, the former “lost boy” known to Americans as the subject of a bestselling “fictionalized memoir” by Dave Eggers, What Is the What, says simply: “The referendum would not have taken place without his involvement. Never. He saved millions of lives. I don’t think he knows this.”

Days after the referendum resulted in a resounding 98.8 percent vote for independence, Clooney was in Detroit, scouting locations for The Ides of March. Recovering from malaria, he was coordinating the release of satellite images and reflecting on Egypt’s uprising: “We’re so interconnected now that I can’t imagine that the south voting for freedom against an oppressive government doesn’t have some effect across the region.” Adds Prendergast: “I don’t think it’s pure coincidence that protests took hold just days after the referendum was broadcast on Al Jazeera. Those images helped empower people. The breeze of freedom from South Sudan became a gale-force wind in Egypt.”

The Republic of South Sudan will not officially become a separate nation until July 9. Obstacles remain, especially Abyei, caught between countries and capable of igniting at any moment. When SatSentinel.org released its first high-resolution photos, it provided visual verification that the north had deployed some 55,000 troops and artillery around the border of Abyei. Whether defensive or offensive, Khartoum could no longer deny the buildup.

“My job is to amplify the voice of the guy who lives here and is worried about his wife and children being slaughtered,” says Clooney, summing up the opportunity and obligation of the celebrity statesman. “He wants to shout it from the mountaintops, but he doesn’t have a very big megaphone or a very big mountain. So he’s asking anyone who has a mountain and megaphone to protect his family, his village. And if he finds me and asks, ‘You got a big megaphone?’ and I say, ‘Yes.’ ‘You got a decent-size mountain to yell it from?’ ‘Yeah, I got a pretty good-sized mountain.’ ‘Will you do me a favor and yell it?’ And I go, ‘Absolutely.’ ”

John Avlon's new book Wingnuts: How the Lunatic Fringe Is Hijacking America is available now by Beast Books both on the Web and in paperback. He is also the author of Independent Nation: How Centrists Can Change American Politics and a CNN contributor. Previously, he served as chief speechwriter for New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani and was a columnist and associate editor for The New York Sun.