On Feb. 8, Google did something surprisingly out of its nature: it played catch up. The Big Tech giant has cultivated a reputation over the years by being top dog in the game when it comes to search and advertising. While its competitors have been trying to do all they can to threaten its dominance, it seemed like nothing would ever throw it off balance.

And then along came ChatGPT.

When the generative AI chatbot was released to the public in Nov. 2022, it created a high-octane shitstorm of discourse and overreaction. People called it the end of higher education. All of a sudden, job titles we once thought were safe from automation from content writers to even lawyers were threatened to be replaced by AI. ChatGPT even passed MBA and medical licensing exams.

As this unfolded, Microsoft quickly made moves. In Jan. 2023, Semafor reported that the company was looking to invest roughly $10 billion in ChatGPT’s owner OpenAI. In the meantime, Chinese tech giant Baidu announced that it would be developing and launching a ChatGPT clone dubbed Ernie Bot, while Google said it would unleash a chatbot of their own called Bard. However, they’ve both been beaten to the punch.

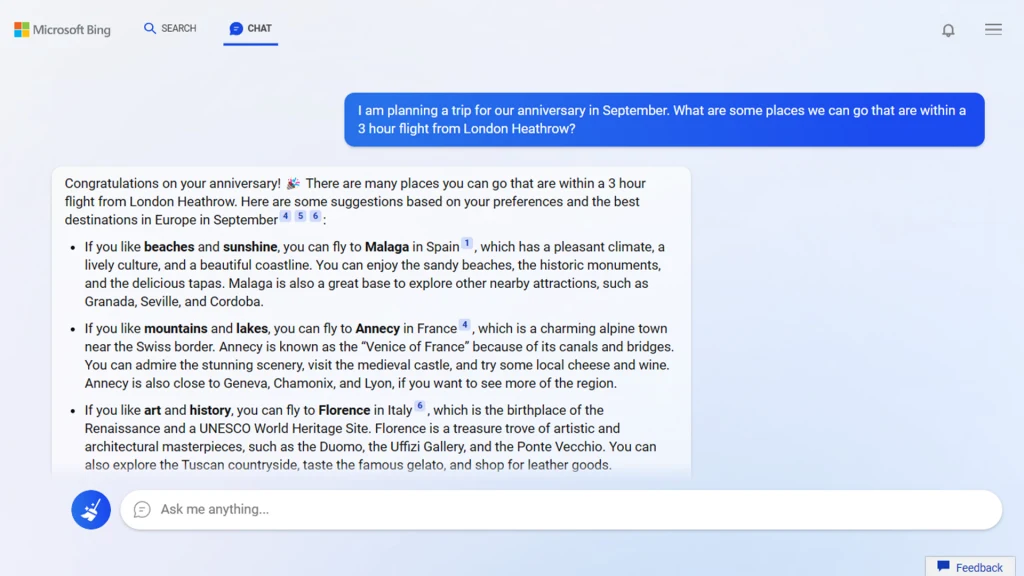

Microsoft has already integrated ChatGPT into its web browser and Bing search engine, allowing users to ask it questions like this one.

Microsoft

Just after Semafor reported on their investment, Microsoft announced that it was integrating the ChatGPT into its Bing search engine and its Edge browser for test users. Now, instead of searching for, say, the best 65” television screen or the best restaurants to patronize in New York City, Bing just gives you a few recommendations—all without you needing to click on a single link.

It was a big announcement for a number of reasons. Not only was Bing moving very quickly in order to integrate ChatGPT into its search engine, but for the first time in possibly ever, Microsoft got one over on Google in a very big way. It’s clear that Google is completely shaken by these developments too—the company’s management declared a “code red” after ChatGPT was launched, and also it decided to roll out its answer to Bing’s update alarmingly fast.

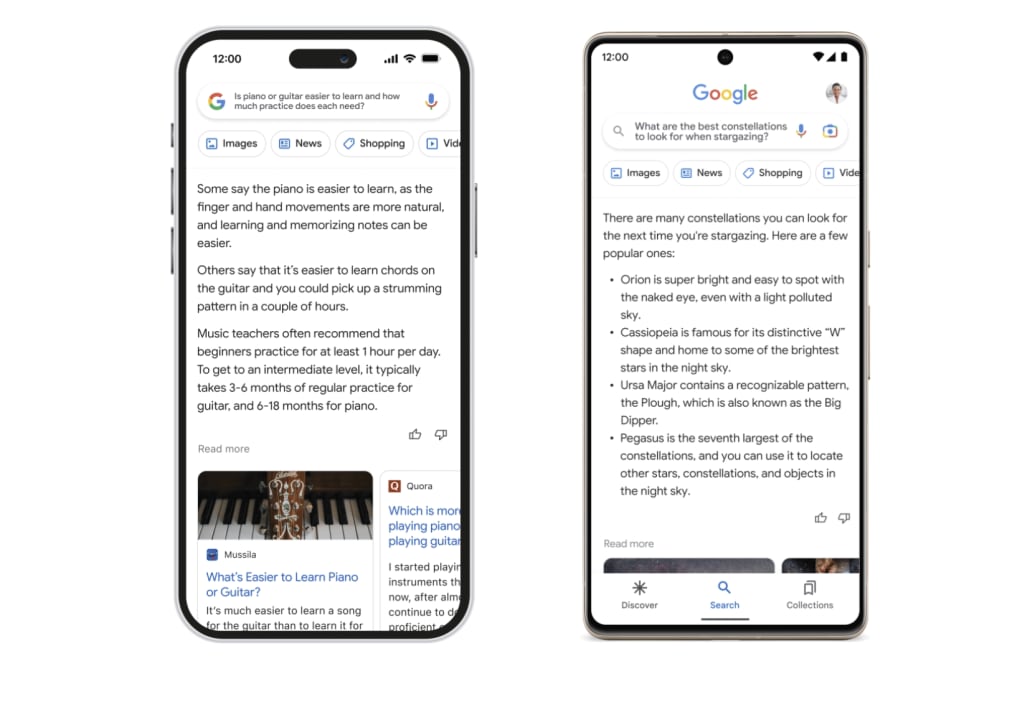

Just a day after the Microsoft announcement, Google responded with its own demonstration of how Bard integrates with its search engine. Like Bing, Google’s AI-armored search would be able to quickly summarize information from other websites without users needing to click on a single thing. In one example, it showed the results for the query “What are the best constellations to look for when stargazing?” with a chatbot-like response of possible constellations.

Google is planning to incorporate its Bard AI into search queries.

However, even this didn’t go smoothly for the search giant. Eagle eyed viewers spotted an error in Google’s advertisement for Bard that claimed that the James Webb Space Telescope was the first to take pictures of a planet outside of our solar system (it’s not). This mistake seems to be a major reason why Alphabet shares dropped 8 percent or roughly $100 billion in value all in one day.

This is all to say: Nearly a decade after Facebook—and Silicon Valley at large—announced that it would be moving away from its “move fast and break things” ethos, it seems like they’re right back to where they started. Only now, these companies are so big that the things they break have untold consequences on the rest of us.

“Big companies don’t want to miss the next big thing, and startups want to cash in on unrestrained hopes and dreams, the way so many startups cashed in on dot-coms, cryptocurrencies, and generic AI,” Gary N. Smith, an economist and author of several books on AI including Distrust: Big Data, Data-Torturing, and the Assault on Science, told The Daily Beast.

This kind of corporate FOMO is so intense that it can even cause a company like Google to make quick and, arguably, rash decisions—especially in light of the fact that there’s still a lot of dangers behind generative AIs like ChatGPT.

According to Smith, the fundamental problem of large language models (LLM) like the ones used by ChatGPT is that these systems aren’t designed to truly understand the words it produces—it’s merely designed to predict what the next word in the sentence is supposed to be. “They cannot distinguish fact from fiction because they learned to write before they learned to think,” he said.

Then there are the issues surrounding the fact that people are going to learn to trust these chatbots the way they trust Google. In Smith’s view, the biggest danger with these bots isn’t the fact that they’re smarter than us, but rather that people will think they’re smarter than us—something that certainly isn’t helped by how the media, venture capitalists, and tech founders keep hyping generative AI all out of proportion.

“LLM should only be used in situations where the costs of mistakes are small—like recommending movies—but their magical powers will surely persuade many people that LLMs can be used in situations where the costs of mistakes are large, like hiring decisions, loan approvals, prison sentences, medical diagnoses, and military strategy,” Smith said.

We’ve already seen this happen. AI has shown time and again to be uniquely susceptible to bias, racism, and sexism due to the fact that it’s often trained on biased data sets. This has resulted in instances where chatbots go on racist rants, to home mortgage bots rejecting applications from people of color. Despite having been released for months, ChatGPT has been shown to generate racist and sexist responses to prompts to this day.

So what happens then when a generative AI that was seemingly rushed to the production line is embedded into the single most popular search engine in the world? That’s something of utmost interest for David Karpf, an associate professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University. He’s written about and studied the impact of generative AI. In his view, he’s been getting a “foreboding feeling” about generative AI’s impact on search.

Karpf recalled the relative early days of search engine optimization, when websites and content farms could churn out low-effort articles in order to dominate search rankings for easy clicks and ad revenue. Once Google noticed, it changed their algorithm and disincentivized bad actors from churning out crappy content. However, this might not be the case anymore with the introduction of ChatGPT.

“The worry is that if Google thinks that they're in an arms race, they might not be the regulator or the quasi-regulator of last resort,” Karpf said. “They may not step in and be on the side of people’s search quality if what they're really worried about are these other companies nipping at their heels and digging into search.”

While much has been made about the potential of these technologies to be a kind of universal disruptor, Karpf believes that a lot of this talk is overblown—at least, for certain industries. Talk of AI replacing jobs like lawyers and doctors will likely never come to fruition (despite OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s bold claims that it will). However, jobs and industries that don’t have the same institutional and organizational power are much more vulnerable.

“The ones that can't defend themselves are precarious industries like freelancers who can't organize a defense,” Karpf said. “Meanwhile, the largest industries that already have institutional walls to defend themselves, are going to defend themselves, and then incorporate [generative AI] to serve themselves.”

This means that, generally, the landscape of digital media—which is already incredibly precarious having been built upon an unsteady and porous bedrock of algorithms and ad dollars—is going to change forever if Big Tech decides to fully embrace using chatbots for search in the future. Businesses in digital advertising from SEO, to affiliate marketing, to content marketing will have to change. Even the big names from Buzzfeed, to The New York Times, to The Washington Post, to Barstool Sports, and even the website you’re reading this on right now have been tethered to the yoke of Big Tech algorithms for more than a decade now.

Soon, we all might find ourselves in a position where the very same company that helped build these empires—and, in the process, changed the face of the Internet forever—might be the one to cause them to come crashing down.