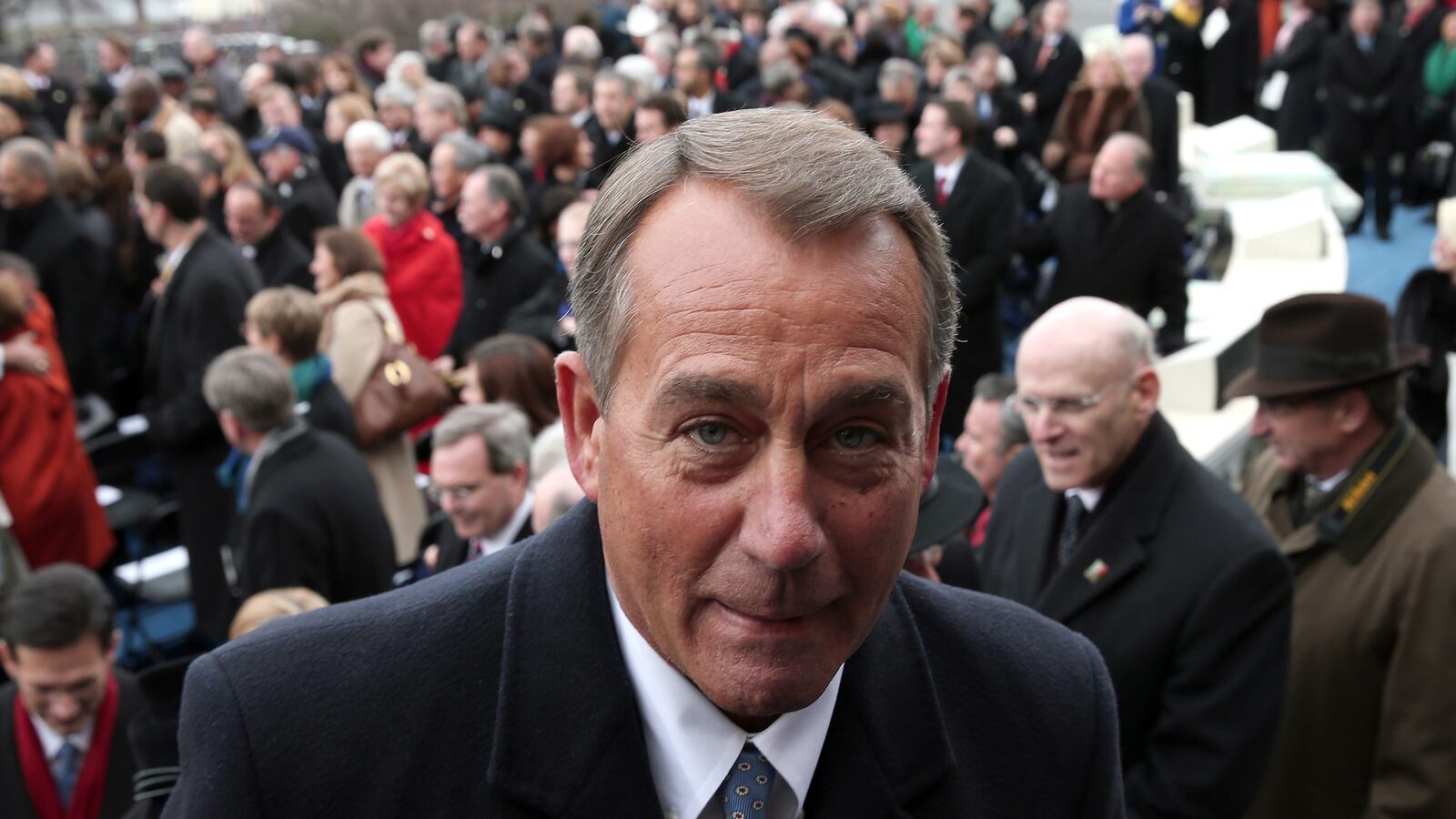

In what a Democratic leadership aide calls “a big cave,” enough Republicans may have been corralled by House Speaker John Boehner to support an extension of the debt ceiling for almost four months. The vote to authorize the government’s borrowing authority until May 19 is expected in the House on Wednesday.

The decision to hold the vote follows a contentious GOP retreat in which Boehner and his top lieutenants stressed how ruinous it would be for the economy, and for the Republican brand, if rebellious House members carried through on threats to let the government default if President Obama didn’t agree to significant spending cuts.

The change in GOP tactics is “pretty simple,” says veteran GOP strategist John Feehery. “They needed better ground to fight.” Flirting with default terrifies the GOP’s benefactors in the business community and would have serious consequences for the fragile recovery. Other deadlines just ahead offer better options for Republicans to get real cuts in entitlement programs, says Feehery, citing March 1, when across-the-board cuts are scheduled to kick in, and March 27, when spending for government agencies must be renewed.

With Obama’s job approval and personal popularity at healthy levels and Republican leaders “underwater,” with more people viewing them unfavorably than favorably in the latest Pew Research Center survey, Republicans were in no position to take on Obama over the debt ceiling.

“What they’ve tried to do is reshuffle the cards,” says Feehery, likening it to a game of solitaire since Obama won’t negotiate, saying it’s Congress’s responsibility. “This is kind of like World War I. It’s almost trench warfare—you battle over inches, not miles. What ends up happening, you have a stalemate. But if you don’t fight as hard as the other side, you lose.”

At the White House, spokesman Jay Carney said the president “would not stand in the way of the bill becoming law.” Should the short-term extension pass the House and Senate and reach his desk, Obama would sign it. It’s not Obama’s favorite way of doing business—he’d much prefer a long-term raising of the debt ceiling—but Carney praised the GOP for backing away from the kind of brinksmanship that occurred in the summer of 2011 and that resulted in the downgrading of the U.S. credit rating.

“We’re glad they’ve abandoned their hostage taking and aren’t demanding cuts in Medicare and Social Security,” says a House Democratic leadership aide, adding, “They’re welcome to put 218 votes on the floor.” The aide made it clear that Democrats aren’t eager to yet again bail out Boehner if he is unable to secure the necessary support for passage from his caucus. The Wednesday vote is a test of Boehner’s leadership and whether he can muster the “majority of the majority” of Republicans for a measure that many, if not most, find distasteful—giving Obama more borrowing power without extracting meaningful spending cuts in entitlement programs in return.

There are constitutional questions in the House GOP’s proposal to withhold congressional pay from members until they pass a budget. The language is aimed at the Democrat-controlled Senate, which hasn’t passed a budget since 2009, deferring instead to various agreements that set spending limits for domestic discretionary spending while leaving entitlement programs untouched. The biggest thing coming out of the GOP retreat, says Feehery, was a determination to force the Senate to take action and get Democrats on the record. “Harry Reid has never shown his cards,” says Feehery.

Tying congressional pay to performance is an idea that’s been kicked around since at least the 1990s. The bipartisan group No Labels recently advanced it as part of a set of proposals to break the gridlock on Capitol Hill. A House leadership aide decries it as “a gimmick,” but it’s got members excited about it in both parties. Republican Rep. Robert Brady testified Tuesday in a House hearing that withholding pay might not affect the Senate so much, since senators tend to be wealthy, but there are a lot of House members who need to make mortgage payments.

The 27th Amendment says changes in congressional pay cannot take effect until after the next election, but putting pay in escrow is a gray area that would likely be tested in court should the proposal get that far. For now, it’s a sideshow in the ongoing struggle between the White House and congressional Republicans over the tough choices that lie ahead about the size and scope of government.